From cherry blossoms to AI robots, from bustling metropolises to tranquil Zen Buddhist temples, from bonsai trees to superfast trains. Japan, and specifically, Tokyo is a curious land of contrasts. All lands are. It's a cliche to even point that out. But Japan seems a particularly fascinating place and one I've never visited. One I'd love to visit sometime.

In the meantime, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is hosting an exhibition, called simply Tokyo, and a few weeks ago I had the great pleasure of visiting it with my friends Colin and Patricia. The experience only made me want to visit Tokyo more.

As befits a city of 37,000,000 residents there was a lot to take on. Most of it was very good indeed. You enter via a corridor mocked up to look like a cherry blossom by Ninagawa Mika. It sets the mood nicely for a brief history lesson before the art tour proper starts.

We learn that Tokyo began as a small fishing village named Edo and that it grew rapidly after the shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, made it his HQ in the 16th century. Edo became a great cultural centre and in the 19th century it changed its name to Tokyo and became the Japanese capital (taking over from Kyoto though Japan had already had many many capitals in its history).

Yoshida Chizuko - A View of the Western Suburbs of the Metropolis - Rainy Season, 1995 (1995)

As is very well known, Tokyo is susceptible to natural disaster. Earthquakes and tsunamis specifically. Yoshida Chizuko's view of the western suburbs in the rainy season shows the sprawling areas most likely to be affected, destroyed potentially, should a serious earthquake hit Tokyo soon.

But it also gives a feel for the sheer vastness of the city. Nishono Sohei's Diorama Map captures that too. Sohei has spoken about how he enjoys walking around Tokyo, losing his way in its alleys, and seeing different worlds open up. I love organising walks in London that aim for this kind of feeling but the idea of doing it somewhere like Tokyo is very appealing to me.

Nishino Sohei - Diorama Map, Tokyo (2004)

Isoda Choshu - Ruins on the Road (1924)

Sohei's image is very much his own personal cartography of the Japanese capital. It's whimsical and overbearing at the same time but images made of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 are only one of those things. There's not a lot of whimsy when considering the deaths of over one hundred thousand people and the razing of nearly half the entire city.

Artists like Isoda Choshu, perhaps because the enormity of the event was too much to take on, looked at small, personal, moments of tragedy in the wake of disaster and his Ruins of the Road has a haunting feeling of a city, understandably, in mourning.

An earlier earthquake, in 1855 - death toll approximately seven thousand, saw the emergence of a new type of Japanese art. Woodblock prints known as namazu-e, or 'catfish pictures'. They'd show mythical giant catfish who it was believed by some caused these regular earthquakes by thrashing about in the underground rivers. Pictures of citizens 'subduing', or attacking, the catfish were quickly banned by the Tokugawa authorities of the time as they were seen to show Tokyo dwellers suffering hardship and as such could be viewed as critical of the government.

Unknown Artist - Citizens Subduing the Catfish of Edo and Shinshu Province (1855)

Fukazawa Sakuichi - Meiji Baseball Stadium (1931)

Maekawa Senpan - Subway (1931)

Like most places, Tokyo likes to show its best face to the world and after the 1923 earthquake, several leading print artists were commissioned to celebrate the rebuilding of the city. Though these works, strictly speaking, are propaganda they are also excellent. There are shrines, bridges, and temples alongside department stores, cinemas and dancehalls so you get a sense of both the old and new sides of Tokyo.

My two favourites, in a packed field, were Fukazawa Sakuichi's sun drenched baseball stadium and Maekawa Senpan's bustling, yet somehow still orderly - a Japanese cliche or a fact, subway station. The prints, like the range of subjects they depict, somehow look forward and backwards at the same time. They are both classic and modern.

It shows a new confidence in the rebuilt city but those living there knew they were still at the mercy of future earthquakes, the fires that would often follow in their wake, flooding from tidal waves, and, later, American bombing of the city during World War II.

Hayashi Tadahiko's photos document both Tokyo's destruction in that war and its redevelopment afterwards. There is poverty and glamour side by side as a new Japan emerges from the rubble. Modern houses stand next to crumbling chop suey restaurants and women in their underwear sunbathe in unlikely locations.

Hayashi Tadahiko - A Dancer Prone (Rooftop of the Nichigeki Theater, Yurakucho) (1950)

Hayashi Tadahiko - Living in a collapsed building (1947)

Onchi Koshiro - Tokyo Station (1945)

Tokyo Station survived the earthquakes but it never survived the war so Onchi Koshiro's print is a memory of the station made later in the year that it was destroyed. It's lovely. I liked it so much I bought a keyring with it on. I needed a keyring anyway but I'm pretty happy with that one.

Koshiro is just one of many Tokyo artists who, over time, have made images of some of the city's most well known, most well loved, landmarks. Looking at images of the Kiyosu Bridge, the Nihonhashi bridge, the boats cruising down the Sumida river with the city's skyline lighting up at dusk in the background, and of course Mount Fuji keeping its stony vigil over Tokyo at all times you can't help but long to be there.

Kawase Hasui - Kiyosu Bridge (mid-1940s)

Sugiyama Mototsugu - Good Evening Sumida River (1993)

Utagawa Hiroshige - Clearing After Snow at Nihonbashi Bridge (1856)

Tokyo, if these images are anything to go by, seems like a sprawling outdoor architectural museum but it's worth remembering that it's not just what Hasui, Mototsugu, and Hiroshige had as subject material that makes these images great but how they chose to present them.

This is the art that proved to be so influential to forward thinking Western artists like Whistler, Van Gogh, Monet, Klimt, and even Jackson Pollock. Its simplicity belies its beauty. It is pensive and yet feels full of motion. Hiroshige, particularly, drew Tokyo as it really was. He drew cherry trees framing tranquil lakes, he drew men and women crossing wooden bridges in rainstorms, and he drew, of course, views of Mount Fuji.

Utagawa Hiroshige - The Suljun Shrine and Massaki on the Sumida River (1856)

Utagawa Hiroshige - Sudden Shower at Ohashi Bridge, Atake (1857)

Utagawa Hiroshige - Suruga Street (1856)

From Suruga Street, Mount Fuji is actually eighty kilometres away but it still dominates the picture and dwarves the ordinary citizens going about their everyday business. Contemporary artists, too, have made use of wood engravings and bold, firmly delineated, colours to emphasise how Tokyo looks to them.

I really liked Yamaguchi Akira's work from the last decade. He's fused fantastical elements into his work but what comes through most strongly is the ordered chaos of the traffic and the Tokyo Tower's dominance over the modern skyline - at least until the Tokyo Skytree (almost double its height and now the tallest tower in the world) replaced it on that front. Yet again we see nature buffeted by modernity. But also modernity buffeted by nature.

Yamaguchi Akira - New Sights of Tokyo:Tokaido Nihonbashi Revisited (2012)

Yamaguchi Akira - New Sights of Tokyo:Shiba Tower (2014)

Takahashi Rikio - Tokyo Tower (1990)

It's the Japanese way! While some Japanese artists, like Akira and Rikio (above), prefer to capture real buildings in the city others prefer to schematically imagine them. Aida Makoto admits a love/hate relationship with the city though admits he will probably live there all of his life.

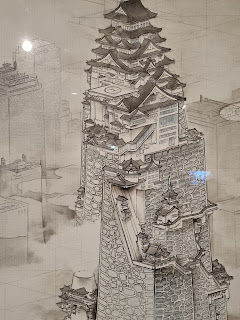

His reimagined Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building as a traditional Japanese castle but one that seems to incorporate, and at the same time mock, the hierarchies that would have been at play in those castles as well as, and this may be simply my interpretation, those that still operate in society today. Both in Japan and elsewhere.

Aida Makoto - Maybe the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building should have been like this? (2018)

Takano Ryudai - Daily Snapshot (2014)

Takano Ryudai - Daily Snapshot (2014)

Either way, it looks interesting. Takano Ryudai is another artist who sees the development of the city as something that is actually quite haphazard. At first his photos look a little dull. Strange subjects to choose when you have the whole of Tokyo at hand. But time spent with them is rewarding as they give you what feels like a more genuine feel for the energy of the city.

As well as not being afraid to look at some of the shabbier aspects. Ryudai's collected several of these in a book under the title of a word he coined himself:- Kasubaba. The fact he says this word means 'junk-places' shows both Ryudai's opinion of Tokyo and also where his interest lies.

Miyamoto Ryuji delves even further into the underground, the dispossessed, of the city. He's aimed his camera at the carboard 'houses' that homeless people in Tokyo, like in so many other wealthy cities around the world, have converted into homes. During the 1990s when Japan entered a financial crisis after decades of boom, these were particularly relevant and noticeable. They are, however - and like many buildings in Tokyo, transient. You couldn't visit Tokyo today and expect to find this exact cardboard house.

Miyamoto Ryuji - Cardboard Houses, Tokyo (1994)

Or, I'd imagine, find the person who once lived in it. The second room at the Ashmolean moves away from the buildings that make up Tokyo to the people who make the city what it is - and what it was.

I don't know what it says about me but I found it the least interesting part of the show. It was still good though. It was a good show from start to finish. Despite being dominated by samurai warriors when Edo first became the largest city in the world, Japan wasn't actually at war for two and a half centuries so the samurai were expected instead to become involved in the arts world.

Both as patrons and as practitioners. Samurai from elsewhere in Japan travelled to the city and ideas were exchanged between them and a new merchant class who supported arts and wanted to see their lives and interests reflected there.

Ceremonial Suit of Armour made for Oda Nobuhisa (18th century)

Arms and armour became more for show, ceremonial, than anything else. Tea ceremonies became ritual events for the warrior class and ownership of prized tea utensils was a sure sign of high status. Many warrior lords even operated their own potteries and imported ceramics from China and Korea.

'No' theatre emphasised Buddhist themes and focused on highlighted, exaggerated even, displays of emotion by leading characters. A quick look at the no masks below and you'll see just how 'enhanced' these portrayals of love, anger, and grief could be.

No masks (18th century)

In 1868, samurai rule came to an end in Japan and the new emperor, Meiji moved himself, and the Japanese capital from Kyoto to the newly named Tokyo (meaning 'Eastern capital'). Japan underwent a period of rapid modernisation and industrialisation and new art schools, museums, and galleries appeared. Japanese artists even started looking further afield than China and Korea, and Japan itself, and began to embrace international art movements.

Although there is still, quite clearly, a very distinct Japanese flavour underpinning everything. Sumo wrestling, which in the past had been so wild it had been banned, reappeared in the form of charity tournaments. Visiting shrines and temples remained popular but often the reason for the visits were more leisure than devotion. Though the giant lantern at the Buddhist temple of Sensoji in Askusa, Tokyo's oldest religious building, looks very eastern, the men in Homburg hats admiring it are adopting elements of western dress.

Utagawa Kunisada - Sumo Grand Fundraising Tournament (about 1844)

Kasamatsu Shiro - The Great Lantern at Asakusa Kannondo (1934)

Tokuriki Tomikichiro - Meiji Shrine (1941)

Nationalism, even exceptionalism, remained too. The cherry blossoms at the Meiji Shrine were painted in 1941 by Tokuriki Tomikichiro with a direct aim of inspiring the Japanese war effort. The emperor of Japan was widely believed to be a direct descendant of the Gods and during World War II this idea was exploited so that Japanese soldiers would kill others - as well as themselves.

As with all nations tarred with exceptionalism, Japanese women and girls had to, of course, be the most beautiful in the world. Ito Shinsui even created a series of Modern Beauties in which he was both able to make loud claims about the beauty of Japanese women and, of course, mix traditional Japanese clothes like kimonos and kanzashis (which I thought, genuinely, were called 'hair sticks') with globally recognisable elegant 1930s chic.

Ito Shunsui - Modern Beauties:Fireworks (1932)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi - The Kabuki Actor Ichikawa Kuzo II in the role of the footman Yokanbel, with a View of Mount Fuji from the Denmacho District (1856)

Natori Shunsen - Matsumoto Koshiro VII in the role of Benkei (about 1935)

Artist unknown, in the style of Hishikawa Moronobu - Yoshiwara Pleasure Quarters (late 17th century)

The role of women in Japanese society, going back centuries, is touched on by an unknown artist's image of a 17th century 'Pleasure Quarter". The Tokugawa shoguns created licensed brothels where all of Japanese society could mix freely (except the samurai who sneaked in anyway - with baskets on their heads so they didn't get rumbled - always a clever disguise).

All of Japanese society except the courtesans it seems, but maybe that's my modern take on it. As brothels go it looks less sleazy than you might imagine but, as we see at the Ashmolean, the Japanese are very good at dressing up. Either themselves, their city, or their indiscretions.

Ninagawa Mika addresses this head on. Her work, we're informed - and can see, is concerned with beauty itself but also with the dark side of beauty. One of her favourite subjects is goldfish. But goldfish injected with dye, her cherry blossoms are mostly clones, and even when her friends' kids have fun it's in the graveyard.

Ninagawa Mika - Tokyo from Utsurundesu series (2018 onwards)

Ninagawa Mika - Tokyo from Utsurundesu series (2018 onwards)

Naito Masatoshi - Tokyo:A Vision of its Other Side (1970 onwards)

They're still eye catching though. It would have been difficult for Naito Masatoshi's erotica not to have caught my eye. Masatoshi wanders Tokyo in the well small hours observing not just the strippers that are active at that time but various other characters including, quite bizarrely, snake charmers.

Tokyo Rumando goes one step further and immerses herself in that world by becoming a character in it, rather than mere spectator. She tours Tokyo's famous love hotels where, in a style that reminded me of the work of Cindy Sherman, she poses as various women who may visit these places. Women who go there with their boyfriends, women who go there to have affairs, and women who go there to sell their bodies.

Tokyo Rumando - Rest 3000- Stay 5000- (2012)

Tsuzuki Kyoichi - Satellite of Love (2001)

Times are changing though and many of these more 'traditional' love hotels are starting to disappear from the city - even though many more Japanese people use them than are ever likely to stay in any of the city's five star hotels. Tsuzuki Kyoichi captured the state of play for prosperity back in 2001. She not just captures the design of the hotels but also the, erm, accessories that are available for visitor's use.

To me, the most famous of Japan's erotic photographers is Araki Nobuyoshi. Some of Araki's work is quite explicit as I found when I decided to browse a large book of his in Waterstone's many years ago. But, and who knows why? - the cost?, he tends to find himself lumped in with fashion, or at least erotica, rather than pornography.

Araki Nobuyoshi - Tokyo Lucky Hole (1985)

Suzuki Harunobu - Woman in a Palanquin Uner a Cherry Tree with Her Maid (about 1767)

His work's a far cry from the wood blocks that were made when Tokyo, then Edo, first became Japan's capital. At least on the surface. Courtesans still appear. Suzuki Harunobo was one of the first of these Japanese artists to work in colour and the example above is rather beautiful.

But so much in this show is. Kobayashi Kiyochika's wistful steam train (hard to tell if he was influenced by Whistler or Whistler by him), Ono Tadashige's proud and modernist celebration of proletarian lifestyles, and even Shimizu Masahiro making one of the banes of modern city life, the traffic jam, something to be elevated and celebrated.

Kobayashi Kiyochika - View of Takanawa Ushimachi Under a Shrouded Moon (1879)

Ono Tadashige - Untitled (1933)

Shimizi Masahiro - One Hundred Views:Asakusa Hirokoji (1973)

Kawakami Sumio - Night of Ginza (1929)

You can really see the European influence on these works - though they remain distinct. Kawake Sumio shows the fashionable Ginza district, where boys and girls would go to show off their new clothes and hairstyles, in the late twenties. It's bold, it's bright, and it must have felt very futuristic in 1929.

Six decades later, Aida Makoto's collage, despite its echo of cherry blossoms, suggests downtown Tokyo as a potentially far darker and more dangerous place. At the time Uguisudani was associated with vice and organised crime.

Alda Makoto - Uguisudani-zu (1990)

Machida Kumi - Three Persons (2003)

I was compelled by Machida Kumi's Three Persons. Not least because of its stark monochrome and bold lines. Also those almost perfectly circular baldheads and also - where is the third of these Three Persons? I had to read the panel next to it to even get a grip on what it was all supposed to mean.

Apparently, one of the baldheads is carrying an electronic charging port that conveys a futuristic atmosphere to a city that is always on the brink of natural disaster. I'm still no clearer but it's a great painting.

Yokoo Tadanori - Word Image Word Image Word Image (1968)

Tanaami Keiichi - No more War (1968)

In a final room of modern and contemporary paintings, it still stands out. The sixties ones are pretty easy to spot from a distance. I like them but they don't look that different you'd have seen coming out the US or UK at the time and they have a very similar anti-war sentiment.

The surreal work of Yamashite Kikuji is, however, quite different. There's a lot of angst in these paintings, a lot of uncertainty, a lot of body parts, and a lot of death. Yamashita had served in the Japanese army in China in World War II and on his return he lived with ravens and owls.

Yamashita Kikuji - Bunker-1 (1966)

Yamashite Kikuji - Funeral Procession (1967)

None of that fully explains what is happening in these paintings of elongated bearded men, free floating eyes, coiled masses, and Satanic moving skeletons but, as with Madia Kumi, it's compelling. Kitaj Kazuo's work is darker still.

Kazuo spent four months with students in a barricaded arts building at Nihon University (protesting about American military bases being still allowed on Japanese soil) and became so familiar with the building that every little nook and cranny seemed to take on its own personality. This grisly looking hook, to my mind, probably doesn't have a very nice personality.

Kitai Kazuo - Barricade (1968)

Aida Makoto - TOKYO 2020 (2018)

I'd not wish to meet the personification of it in real life. The show ends with some very recent protest art by Aida Makoto and Murakami Takashi that shows that both the protest movement and the move towards new and thrilling ways of making art is still strong in Japan.

The Tokyo Olympics, as with most large sporting events, were controversial long before they were postponed and then finally played out, a year later, to a television audience as Covid prevented spectators attending in any significant numbers. Aida Makoto has made a fairly light work to make that point. Murakami Takashi ends the show, however, in the way everything must end.

Murakami Takashi - Death, Multi (2015)

Though luckily not for us. At least not yet. Thanks to Colin and Patricia for accompanying me to this wonderful exhibition and for their company during a not inconsiderable debrief in the hostelries of Oxford afterwards.

No comments:

Post a Comment