Ad Montes Oculus Levavi, the motto of the county of Cumbria, means, in Latin, "I have lifted up mine eyes to the hills" and while you're watching The Lakes with Simon Reeve (BBC2/iPlayer) you may find yourself, even though it's on television and you're not really there, doing the same.

But Simon Reeve, more so than ever these days, is not in Cumbria merely to enjoy the beauty and the majesty of the landscape. He's there to look at the lives of the people who live there. The farmers, the men and women who work at Sellafield, the disaffected youth of Barrow-in-Furness, the firemen, and the almost militant protectors of the red squirrel population.

If there was any fear that Reeve, presumably Covid enforced, being in the UK rather than gallivanting around the globe would reap slimmer dividends than usual then that is put to bed very soon in this three part series. If anything, getting a closer look at our own country is more interesting. That's something that pandemic enforced local lockdown walks and the last six years of TADS have taught me anyway.

There is always unexplored beauty and fascination on our own door step. We simply have to go outside and look for it. Having said that, I've not been to Cumbria or the Lake District since I was a teenager (and on that holiday, to be honest, I was far more excited about visiting Blackpool Pleasure Beach - to the south in Lancashire) even though I'd love to do a TADS walk up there. Two of my best friends, Shep and Michelle, are actually from Cumbria.

Although, perhaps noticeably, neither of them have lived there for quite some time. Not that that means the Lake District is anything like empty. On an average year it receives twenty million visitors and as more of us holiday at home due to pandemics and climate issues that figure is expected to rise even higher.

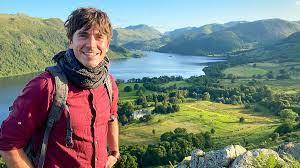

It's understandable. It really is beautiful. Reeve is Tiggerish most of the time so, of course, the series is punctuated with shots of Reeve, often standing atop a cliff like Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, liberally dishing out superlative adjectives. If it's not spectacular, it's stunning. If it's not stunning, it's astonishing. If it's not astonishing, it's incredible.

There's a lot to be Tiggerish about. But when you see how much it costs to holiday in some parts of the Lake District you could turn Eeyore pretty quickly. A luxury hotel and spa Reeve visits will set you back somewhere between £1,000 and £2,000 for a week's stay and not all of this money goes back into the local economy.

Though small numbers of locals thrive by letting their houses out as AirBnBs, many more begrudge the fact that these, and even more so the second homes that now dominate the region - more than half the houses in the Lake District are now second homes, are driving up prices and making houses increasingly difficult, impossible for many, to afford.

Reeve, with the BBC behind him, could probably manage the cost but, for the experience, he sleeps in a converted shepherd's hut that's said to be the country's most remote hostel and spends another night in a barely used church that looks out to the valley that inspired the setting for Postman Pat. There's not as many trees as you might expect. The Lake District is only 12% forested (Greater London, in contrast, is 21% forest) so it seems a surprise, a tragedy even, when you see people chopping down some of the trees that are there.

As ever, it's more complicated than it first appears. The trees being felled around Ennerdale Water are sitka spruces and their natural home is on the North Eastern US seaboard and Canada. In Cumbria, they tend to dominate which means less other trees. On top of that they're not particularly liked by the local wildlife.

So the plan is to chop the sitka spruces down and plant some new, better - at least for this environment, trees. To rewild the area. Elsewhere in Cumbria, Reeve wobbles on a boggy raft of sphagnum moss and looks at ospreys that are known to migrate to and from the Gambia. It's not just the flora that needs rewilding in the Lake District, it's the fauna too.

Reeve goes red squirrel spotting and learns that around a quarter of all UK mammals currently face extinction. Red squirrels are primarily under threat from a pox carried by their grey cousins. Julie, Reeve's guide, shoots and kills the greys and makes waistcoasts from their pelts. Occasionally, she'll cook them. Her partner enjoys a squirrel madras.

It's not a dish I'd wish to try. But then I don't eat meat. Most of the animals you're likely to see in the Lake District, though, will one day end up on somebody's plate. For a lot of the time on his journey, Reeve is surrounded by sheep. Hundreds of thousands of them, nibbling the landscape bare much to the annoyance of some observers.

Farmers have the right to graze their sheep on the 16% of the Lake District that is designated common ground but when Reeve meets upland sheep farmers during lambing season they tell him that earning a living is getting harder and harder. Wool prices are currently very low and, in the UK, we tend to import cheap lamb to eat rather than pay for the British stuff.

It doesn't seem a problem that Brexit is likely to solve. Elsewhere, there is tension between the farmers and water companies like United Utilities who own much the land and operate the reservoirs that provide North West England with most of its water.

Interesting points are made about how conservation could work alongside agriculture. But in the immoderate debates of our current culture there seems little appetite for finding the common ground. Reeve learns how Galloway cattle are not only prized for their beef but come in handy with rewilding in the area and he is treated to a very rare sighting of a natterjack toad in the threatened (and vital for both us and the toads) sand dunes along the almost deserted one hundred miles of Cumbrian coastline that stretches from Morecambe Bay to the Scottish Borders.

More people seem to be swimming in the cold looking lakes than in the even colder looking sea in Cumbria but when he meets wild swimmers at Buttermere the story he hears from them is not wildly different to the ones he's heard elsewhere. Stories of nature in crisis. New Zealand pygmyweed, another invasive species, reduces oxygen levels in water and that kills native species. The pygymyweed from down under is so abundant in Derwentwater that swimming has now been banned.

It was brought to the UK as an aquarium plant but as soon as it reached wild water it began to take it over. You get so much as the tiniest bit of it on your paddleboard and it's liable to follow you to your next destination.

Walking's still a good option in the area though (unless you want to drive around in a convoy of expensive McLarens and other sports cars as some dicks do, turning a place of natural beauty into a rich man's playground) and at Scafell Pike, England's highest point, Reeve meets with the ranger, Ian, who maintains the very well trod path to the top.

It's physically demanding work, that's for sure. But, so it seems, much of the work around Cumbria is demanding in some way. Barrow-in-Furness is quite a remote and unique looking place. A town built around the shipping industry, there's some pretty impressive - and expensive, you won't get much change from one and a half billion quid - nuclear submarines stationed there.

Circumnavigating the globe as the UK continues with the pretense that it remains a world power, they area at the forefront of UK defence. BAE employs 9,000 people in and around Barrow. They're just beaten, in terms of numbers, by Cumbria's largest private employer further up the coast. Sellafield, which employs ten thousand directly, is a huge, and very rusty looking, industrial complex that was set up to make nuclear bombs and now houses the largest stockpile of plutonium on the entire planet.

It's also the site of the biggest decommissioning project in history as we try to put right past wrongs. The project is expected to last for a century and cost the UK £100 billion. If BAE and Sellafield seem at odds with the nearby Lake District's pastoral history, though, then that's not really the case. The Lake District was once, itself, an industrial landscape.

A landscape of mining. Particularly slate mining. The one remaining British slate mine is still there and the slate from there is of such a high standard that it comes with a three hundred year guarantee and can be found in Buckingham Palace and St.Paul's Cathedral. But for our more everyday slate needs, say gravestones for example, we tend to import these days.

On a huge scale too. The UK imports 20% of the world's slate - often from China, India, and Brazil where labour is cheap and there are far fewer protections for workers. Again, for Brexit to 'work', we would need to lower our workers' safety standards and that would almost certainly lead to more accidents and even deaths.

Everywhere you look, if you look through my eyes, you can see both why Brexit had happened as well as why it is failing. The government, of course, try to distract us with promises of 'levelling up' and 'taking back control' but even when the boasts aren't hollow (as they so often are) they are divisive.

Near the former Haig Colliery in Whitehaven (which last produced coal in 1986 and as with Sellafield is a must see for those with a penchant for rust), the government (and I don't think they shouted too loudly about this at the recent COP26 in Glasgow) has announced plans to open a new coal mine. Coal being one of the dirtiest of all fossil fuels, it's not gone down well in many places.

It may be good for jobs but it will definitely be bad for the environment. In Whitehaven, a former prosperous rum importing town that lost most of its business to Liverpool and Glasgow decades ago, there seem to be more for it than against it. I rather suspect it's yet another case of the government dangling a promise in front of potential voters, getting their votes, and then changing their minds. Thus, leaving everyone more divided, and more unhappy, than before.

We've learnt the hard way that's how Boris Johnson operates. But issues of economy and climate change are larger than, existed before, and will outlive Johnson. Reeve visits the 'energy coast' off Barrow to look at one of the world's largest offshore wind farms. It's an impressive sight and it's an admirable achievement but, sadly, it's not one that Britain can claim as a victory.

Or at least not solely. The wind farm is owned and run by a Danish company, Orsted A/S, and many of the components used are German built. At least the locals have the option of getting jobs there though and it is the people of Cumbria, more than even the landscape and the industrial history, that provide us with the most poignant parts of this series.

When Reeve follows disadvantaged youngsters, some who'd rather stay in their rooms staring at their phones, on an activity trip to Windermere there's a telling, and moving, moment. After canoeing across the lake, Reeve tells the kids that they are "intelligent" and "impressive". They are genuinely shocked. One remarks that nobody has said that to him for years.

I'm moved. I'm moved too, in even more upsetting ways, when Reeve visits a women's (and now men's too) refuge in Barrow. It's there for those who have suffered domestic abuse, those in poverty, and those without a roof over their heads and there are rows upon rows of clothes there for people who can't even afford £1 to buy a t-shirt from Primark.

Free sanitary products like tampons too and, predictably but worryingly, 'fleebags' for women who need to escape abusive partners immediately. For those who simply don't have time to pack.

The youngsters on Windermere and the volunteers who work at the women's centre provide hope against a backdrop of an increasingly cruel, uncaring, and hostile society (just as Priti Patel likes it) but even more touching, and in fact truly amazing, is the story of eighteen year old Angus.

Following the death of both of his parents in a year, his father in a quad bike accident and his mother from stomach cancer, eighteen year old Angus has found himself in the unenviable position of being in sole charge of a farm that provides meat for Asda, ALDI, and Lidl. With two seventeen year old friends assisting him between studies, he appears to making a pretty good fist of it but what a responsibility for a teenage boy.

My main concerns at that age were if a girl fancied me and when the next Jesus and Mary Chain album was coming out. Angus is a perfect candidate for a Simon Reeve show because Reeve, it seems to me inherently, sees the good in people. He listens to them, he learns from them, and even when he disagrees with them, he never judges.

For all the lessons on dry stone walling and visiting McVities biscuit factories and castles (both in Carlisle, an "underrated gem" according to Reeve - the castle is where Mary, Queen of Scots was held prisoner and is said to be the most besieged in the country), Reeve is at his best when he is talking one to one with a person about their life, their work, and their passion.

That's worked in every series of his I've seen and, in Cumbria, it worked better than ever. But as befits the time of climate crisis we're living in, these special guests now make up part of a much wider narrative. That of the future of our planet. To tell the entire story of that is too much to ask of any one person but Reeve commits to the brief he has inherited with just the right levels of passion and curiosity.

Carlisle, with three rivers - the Eden, the Caldew, and the Petteril - all flowing through it, is highly susceptible to flooding. Further upstream from Carlisle, Reeve meets a couple of men who teach him about the importance of meanders in rivers. They slow the flow of water down and this not only do they reduce instances of flooding in cities like Carlisle but they also create better habitats, such as river islands, for sustaining wildlife.

When the river flows too fast the fish can't cope, the trees on the islands and the animals that live on them can't cope, and, ultimately, our cities, and those that live in them - us, can't cope either. Meanders do a wonderful job in slowing down the pace of water so that we can use and enjoy it rather than be overwhelmed by it. Reeve appreciates this and his own programmes reflect that by meandering pleasurably towards uncertain conclusions rather than overwhelming us with rhetoric. Now it's for the rest of us to learn to meander. Going full speed through the countryside, like the boy racers in their McLarens, is no way to appreciate it and it's no way to sustain it.

No comments:

Post a Comment