I've seen a Cindy Sherman exhbition at the Broad in Los Angeles, I've seen a small joint show with David Salle at the Per Skarstedt in Mayfair, and I've seen her work in many thematic retrospectives (Gagosian's Visions of the Self:Rembrandt and Now, The Photographers' Gallery Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, and even the V&A's Botticelli Reimagined to name just three) but her current retrospective at the NPG (National Portrait Gallery) is surely the most comprehensive collection of her work yet.

Untitled #316 (1995)

Comprehensive for sure - but, at the end of it, I'm still not sure I know that much more about Cindy Sherman herself and I get the impression that's how she likes it. She doesn't wear all these masks, don all these prosthetics, play all these characters, and invent all these scenarios so we can learn something about her. More likely, she's trying to tell us something about ourselves, the society we live in, and the role women play, and are permitted to play, in that society.

Sometimes the work is subtle, sometimes quite the opposite, sometimes the results are funny, at other times quite grotesque. As Sherman herself as said "Everyone thinks these are self-portraits but they aren’t meant to be. I

just use myself as a model because I know I can push myself to

extremes, make each shot as ugly or goofy or silly as possible".

To ease us into the exhibition we're initially treated to a small selection of ongoing work commissioned by fashion magazine Harper's Bazaar three years ago in which Sherman has photographed herself wearing outfits by the likes of Chanel, Prada, Gucci, Marc Jacobs, and Miu Miu. It's a collection that Sherman subtitled 'project twirl' and it's her intention to put fashion show attendees under the microscope, to see how the spotlight affects those in its glare, how people behave when they're being observed and when they feel they're important.

As ever, narratives are hinted at rather than explicitly drawn up. The viewer is left to do the heavy lifting. It's a good way of showing where she's at, as an artist, right now but it's not the most interesting thing on show by some stretch. For that, we'll need go back over forty years and pick up Sherman's career trajectory from the mid-seventies when she left Buffalo State College in New York state.

Untitled #602 (2019)

Untitled #588 (2016/2018)

Untitled #587 (2016/2018)

In fact a lot of the work shown in the exhibition's first few, slightly crowded, rooms were made when Sherman was still studying at Buffalo. We see how she went from facial alteration to full body alteration in a few short years, we see a doll come to 'life', and we see Sherman posing as an Unhappy Hooker waiting for a client as well as playing all the characters in a Murder Mystery. I Hate You (1975) features Sherman mouthing those three little word before bursting into tears

1977's Line-Up features Sherman playing thirty-five different characters, differentiated by make-up, wigs, masks, and costumes and, with this, we can see how fully formed Sherman's art, and the concepts that underpin it, was from very early on.

1977's Line-Up features Sherman playing thirty-five different characters, differentiated by make-up, wigs, masks, and costumes and, with this, we can see how fully formed Sherman's art, and the concepts that underpin it, was from very early on.

She'd dress up as and act the role of any number of characters. Detectives, butlers, maids, murder suspects, and twenties style flappers. It didn't even matter if they were male of female and it wasn't particularly important how realistic they looked. In fact, obvious artifice was one of the points she was trying to make. When she shifted from black and white to colour and, one would imagine, had more money to work with, the works became more outlandish and unrealistic, not less.

Untitled A-E (1975)

Untitled (Line-Up) (1977/2011)

Untitled (Line-Up) (1977/2011)

Untitled (Line-Up) (1977/2011)

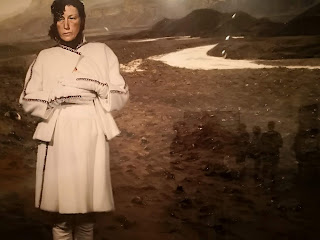

Moving into the eighties, Sherman appeared to become more interested in the media of cinema and there's a selection of works called Rear Screen Projections and Centerfolds that remind me of photographers like Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson (Wall was around before Sherman, Crewdson came after) in that they look like film stills but they are, in fact, staged with no little precision to fool us into thinking that.

Again, artifice. Once more into the illusion. These characters, all women, share a vulnerability. A not uncommon trope in Hollywood and one that reinforces patriarchal values even if unknowingly. We, the viewers - especially hetero male ones like me, are complicit in this voyeurism and objectification. We can hardly not be. We may not agree with systems that have been created through years of gender inequality but we're part of them, whether we like it or not.

Untitled #66 (1980)

Untitled #96 (1981)

Untitled #72 (1980)

Untitled #76 (1980)

Hitchcock was a great film director, of that there can be no doubt, but he was also a master of placing women in peril. I spoke to a friend, a female friend - and one who'd studied this very subject, on this so I wouldn't be writing this piece entirely from a male perspective and she said she thought many of Hitchcock's films "portray women negatively and show, at base level, his fear of them" and that his female characters are often "psychotic", "manipulative", and "hysterical" while at the same time always giving off "an air of perfection and beauty".

It's unlikely Hitchcock would be the only director of his era to do this but as one of the most important, and still relevant, it's worthwhile to look at his work through modern eyes and try to make sense of whatever his motivations were. Sherman's next series, Pink Robes and Color Studies (1981-2), showed her, now, subverting that vulnerability.

She's 'caught' without make-up, covered only by a pink bathrobe, but instead of the shy and retiring subjects that pervy old Degas created by peeping through keyholes, Sherman stares out directly at the camera as if to dare us to meet her eye. But, even here, this candid approach is not the whole story. Sherman, again, is playing yet another character. Or, more correctly, layering one of her existing characters. These 'starlets' of the screen and stage have their downtime, their quiet moments, and it seems, and the curators of this retrospective gently push us towards thinking, that Sherman is simply acting out the role of the actor instead of the character here.

Untitled #114 (1982)

These colour series are the natural successors to a previous collection of Sherman's, Untitled Film Stills (1977-80) also looks to Hitchcock but also, to this blogger's eyes at least, to the French new wave and Italian neorealism. These stills could come from a Luchino Visconti or a Francois Truffaut film as easily as they could a Hitchcok or an Otto Preminger.

Sherman is cast stoically smoking, confused on a staircase, adrift in some unnamed Mitteleuropa, or scantily clad on a bed or window ledge. The artist is relying on our knowledge of cinema history to put the pieces together, to create our own narratives and then, it is to be assumed, she's also relying on us to take a look inside our selves and self-appraise why we see the photos this way. Have we been conditioned to view images of women in a certain way?

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

Untitled Film Still (1977-80)

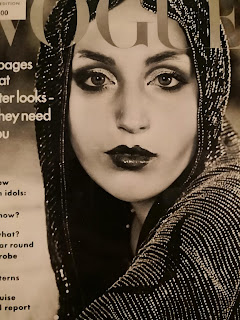

Creating our own narratives is easy, we do it all the time. It'd be harder not to. Digging in deep for a self critique is more difficult. Denial flows naturally in our fragile sense of self. In 1976 Cindy Sherman made a much more politically forthright, and more fun if less complex, series called Cover Girls.

Originally displayed on the top deck of a bus, the series comprised five different works each consisting of 'covers' of women's magazines (I've chosen Vogue and Cosmopilation mainly for their renown, but the lesser known Family Circle, Mademoiselle, and Redbook were included too) and each containing three images. The first is the original magazine cover, the second sees Sherman transformed by clothes and make-up in an impersonation of the model, and the third and final image is Sherman again, retaining the impersonation but with a 'goofy face'!

This manipulation of mass media, that's Jerry Hall on the Vogue cover btw, is all about asking us to question where we get our information from. It is a form of detournement used by situationists, the more intellectually mineded punks, and Joe Orton. It may seem crude but its effectiveness cannot be denied.

Cover Girls (1976)

Cover Girls (1976)

Cover Girls (1976)

Cover Girls (1976)

Cover Girls (1976)

Cover Girls (1976)

The exhibition isn't laid out in strict chronological order which once would have irked me. But in the case of Cindy Sherman it's quite nice, illuminating even, to flip forwards and backwards almost as if at whim. Her recent Flappers (2016-18) series does that anyway, looking back to the styles of the twenties. Styles that look pretty tame now but, at the time, flouted convention.

As did some of the behaviour. Smoking in public, wearing make-up that was obvious rather than understated, and appearing to be sexually liberated. Sherman's flappers, however, seem to be older women appropriating younger styles and I have to confess I'm not quite sure what she's getting at here. The old cliche of 'mutton dressed as lamb' is as offensive as it is dated and it seems highly unlikely that a modern thinking, and feminist, artist would be laughing at older women for daring to care about their image. Surely not?

Untitled #574 (2016)

Untitled #567 (2016)

Untitled #137 (1984)

Surely not indeed! Yet, occasionally, I have my doubts. It's probably me getting the wrong end of the stick but there's more than the odd image on show that reminded me of Martin Parr. I've long suspected Parr, with his supposed appreciation of working class culture, is actually sneering at those he claims to be representing (I have similar problems with Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party) and, at times, I suspect that Sherman, who as far as I know has never claimed to represent ALL women, can't resist a little sneer.

Maybe it takes a woman to truly know a woman. It'd certainly be problematic if a male artist had made these images. Sherman has said "I'm disgusted with how people get themselves to look beautiful" which does seem a little disproportionate. Nobody should feel under pressure to make themselves attractive to others but, equally, nobody should be criticised for wanting to do so, and certainly not for doing so just because they feel like it.

Wearing nice clothes can make you feel better and for someone so keen on dress up to knock others for doing it seems a bit cheeky. The NPG, due to its layout more than anything else, have split the exhibition into two parts and in the room between those two parts we can see some of Sherman's dressing up kit. Masks, wigs, and prosthetic tits all stacked up on shelves as if you'd popped round Ed Gein's place by mistake.

Wearing nice clothes can make you feel better and for someone so keen on dress up to knock others for doing it seems a bit cheeky. The NPG, due to its layout more than anything else, have split the exhibition into two parts and in the room between those two parts we can see some of Sherman's dressing up kit. Masks, wigs, and prosthetic tits all stacked up on shelves as if you'd popped round Ed Gein's place by mistake.

Untitled #216 (1989)

As you'd expect after such macabre artefacts, the tour into Sherman's career turns a darker corner at this point. Artful, even disturbing, close ups of hard to read masked faces peer out at us in garish colour and she dons a series of clown outfits, presumably with the idea that a small element of coulrophobia lies within us all.

But I've never found clowns particularly scary, or sinister. Just a bit shit really. I've certainly never found them funny with their stupid water spraying buttonhole flowers, their crappy cars that fall to pieces, their dumb red noses, and their massive shoes. Clowns can fuck right off.

Untitled #317 (1995)

Untitled #413 (2003)

Untitled #424 (2004)

If clowns equally repulse and amuse children, perhaps the adult equivalent is pornography. I know it's meant primarily as an aid to masturbation but, sometimes, the images are pretty grotesque and the lack of context can render what might be pleasant in real life somewhat 'medical' on the page (or, now, on the computer screen). The porno mags me and my mates used to find ripped up round the back of the garages occasionally featured a centre spread of several women's vaginas all piled up on top of each other. It was known as a 'stack'. and I'm willing to bet nobody but the richest, most amoral, deranged pervert has ever witnessed a stack in real life - and even then they'll have definitely paid for the experience.

Sherman's attempts to show how pornography can dehumanise can hardly fail to fall short of stacks but it's still pretty damn effective. Taking her cues from the surreal art of Hans Bellmer, she's arranged her dolls into submissive and sexual poses but their unreal limbs and expressionless faces suggest a joyless, loveless, experience rather than an erotic one - and that's before you even get to the one with Prince Philip's face and a lengthy brown thing (a turd perhaps) emerging from, or perhaps entering into, his/her vagina. Sweet dreams!

Sherman's attempts to show how pornography can dehumanise can hardly fail to fall short of stacks but it's still pretty damn effective. Taking her cues from the surreal art of Hans Bellmer, she's arranged her dolls into submissive and sexual poses but their unreal limbs and expressionless faces suggest a joyless, loveless, experience rather than an erotic one - and that's before you even get to the one with Prince Philip's face and a lengthy brown thing (a turd perhaps) emerging from, or perhaps entering into, his/her vagina. Sweet dreams!

Untitled #255 (1992)

Untitled #250 (1992)

Untitled #302 (1994)

Perhaps rightly so, the pornography room contained a warning about the images in there and suggested it might not be suitable for children. No shit - though as it turns out there appeared to be some actual shit! 2008's series of Society Portraits, and in fact the rest of the show, is necessarily tame in comparison as anything would be once you've seen a transsexual image of the Queen's husband with a big lump of shit up his fanny.

Again, Sherman seems to be knocking the rich (fair enough) and the old (not so good) and their penchant for cosmetic surgeries in an attempt, often forlorn, to prolong their youthful appearances. It seems likely, probable even, that in the upper echelons of society this behaviour isn't so much as it is expected. It's a type of peer pressure that those of us from the lower orders find difficult to understand. Although at least we can still understand, to a degree, each other's facial expressions if we've not Botoxed any semblance of nuance out of our features.

Sherman has said "it's especially scary when I see myself in these older women" and in that she is, and this seems quite rare in her work, admitting that these are, in some small way, self-portraits. Suggesting, perhaps, that all art is in some way a self-portrait. You can paint landscapes, you can photograph whoever you like, and you can write songs about people you love but everything you see, everything you do, and everything you create is viewed through the prism of the very real situation of being yourself.

Yet it's when the humanity shines through the artifice that the work is at its most powerful. Sure, it's fun to laugh at people - but if you don't include yourself among the people you laugh at then that's not a sense of humour, that's just bullying - and there's more than enough of that in America, Britain, and the world today. Cindy Sherman is at her best when she remembers that. Luckily for us, she does so more than she doesn't.

Untitled #475 (2008)

Untitled #465 (2000)

Untitled #466 (2008)

Untitled #546 (2010/2012)

Untitled #549 (2010)

Thanks to Michelle whose degree in, and knowledge of, feminism within avant-garde cinema provided me with some insight for parts of this blog. Oh, and also for pointing out the sex doll's likeness to HRH Prince Philip. An image it'll take a while to erase from the retina in which it is now permanently etched.

No comments:

Post a Comment