There's no country in the world I'm not curious about visiting but I have to admit that Japan has never been at the very top of the list. Of places I haven't been (or haven't really spent any time in) I'd put Thailand, Indonesia, Brazil, Chile, and Georgia higher. Or at least I would have done until I watched BBC4's excellent three part documentary The Art of Japanese Life (with presenter James Fox immaculately turned out in black suit, white shirt, and black tie throughout).

Now, Japan has shot to very near the top of the list (despite being way out of my current price range). How could I not love a country whose culture embraces not just art, architecture, and music, but nature, food, gardens, tea, and even silence and space. There's a danger of exoticising the country and, on occasions, Fox steers close to the edge on this but he (and his team) always remember to balance that out with a good old fashioned dose of reality.

Cherry Blossom

One of the most tired cliches of the travel writer is to call somewhere "a country of contrasts". Not least because everywhere is. Japan is certainly no exception. It is one of the most densely populated places on Earth and most of its citizens live in big, vast even, cities yet 73% of it remains uninhabited. It has 10% of the world's volcanoes and suffers a terrifying amount of earthquakes so perhaps it's no surprise that Fox kicked off with an episode devoted to 'nature'. The following two programmes would drill down on 'cities' and 'home'.When the Gods plunged a spear into the endless ocean, drops of water formed a series of islands which became the whole known world. That world was Nippon, the Land of the Rising Sun. That, at least, is the creation myth of Japan. It's no odder than any other religious creation myth but it does, perhaps, explain a bit about Japan's insular, and island, mentality. It's often perilous natural features may explain why the Japanese are so awed by nature.

The Japanese revere mountains, a belief enshrined in Shinto - the traditional religion of the country. It's a religion with no founder and no scriptures, a religion that believes the world is inhabited by spirits called kami that live in the sun, the wind, and the rocks, as well as in trees and animals. Hence the divine is everywhere and shrines are found all over Japan. Sometimes in breathtakingly beautiful places.

Nachi Falls

With every element of nature deemed worthy of respect, it's no surprise that art and decoration should reflect that. Netsuke are miniature sculptures that were used as toggles on the sashes of kimonos and many of them were fantastically detailed and intricately carved. They depict a variety of natural themes (an ape riding a fish for example) but the boxwood cicada, below, is particularly valued. Cicadas being seen as symbols of both summer and melancholia.

Netsuke

Netsuke

Japanese literature regularly features dragonflies, fireflies, and beetles and many Japanese keep insects as pets. While a (small) majority of Japanese adhere, at least in name, to Shinto there is a significant number of, about forty million, Buddhists in the country and they too, you'll not be surprised to read, are big on nature. I learned a lot of things I didn't know with this series but I did, also, learn a few things that I already knew!

The Buddhist belief in reincarnation, in its Japanese iteration, extends to wind and rocks. There are numerous sects but Fox is looking at Zen Buddhism which, like Shinto, also has no scriptures. The important parts of Zen Buddhism are meditation and repeated, and repetitious, practical exercises.

Sweeping the garden or cooking for example. This rigorous ascetic training is believed to discipline the mind although Zen monks have also practiced painting for these purposes. The most famous of all these 'ink and wash' painters was Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506). Toyo was inspired by Chinese art but there's a far more poetic story about him that insists he was so talented he could paint with his toes using his tears as material after he'd been tied up. He painted a rat that was so realistic it came to life, gnawed through the rope that was keeping him bound, and set him free.

Sweeping the garden or cooking for example. This rigorous ascetic training is believed to discipline the mind although Zen monks have also practiced painting for these purposes. The most famous of all these 'ink and wash' painters was Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506). Toyo was inspired by Chinese art but there's a far more poetic story about him that insists he was so talented he could paint with his toes using his tears as material after he'd been tied up. He painted a rat that was so realistic it came to life, gnawed through the rope that was keeping him bound, and set him free.

Sesshu Toyo - Landscape

Sesshu Toyo - Landscape

Sesshu Toyo - Splashed Ink Landscape (1495)

Hasegawa Tohaku - Pine Trees in the Mist (c.1595)

The spaces in between the elements of the landscape is just as important as those elements. You can see it in Tohaku's wonderful, almost spectral, Pine Trees in the Mist from the late 16c. The space acts as a visual metaphor for Zen meditation. Zen not only inspired artists to depict the natural world, but also to recreate it.

Ryoan-ji in Kyoto is not a garden for walking in. It's one for contemplating. It consists of a bed of carefully raked gravel, moss, and fifteen precisely placed stones. Fifteen because fifteen symbolises completeness in Zen (representing the seven continents and eight oceans) and precisely placed because it's important that you can never see all fifteen stones at the same time. A reminder of human imperfection and a reminder that answers are less important than our endless search for understanding.

Ryoan-ji Temple, Kyoto

Bonsai

Uzushio (Whirlpool)

Nature and culture also come together in the Japanese passion for bonsai, like so much in Japan initially an imported idea from China. Some bonsai, like the famous Uzushio (Whirlpool) above, are up to five hundred years old and there are museums devoted to bonsai. It's a high end pastime. Uzushio is about the same age as Michelangelo's David but, despite the dead wood that has been intentionally cultivated, it's a living sculpture. Even Michelangelo couldn't manage that.

It's not just aged nature that the Japanese find beauty in. Cherry blossoms have been revered by the Japanese for a thousand years precisely because of their fleeting nature, because they are a constant reminder that everything must pass, a memento mori made by Mother Nature herself.

In the months of March and April, millions of tourists visit Japan to join in ceremonies that celebrate the beauty, and transience, of the cherry blossoms. All seasons are celebrated in Japan, the seasons are quite extreme there, but spring is the one that really brings in the visitors.

Cherry Blossom

Ogata Korin - Irises (1710)

With Japan being late to develop a written language, art and nature became vital forms of self-expression. Ogata Korin's beautiful six panel Irises celebrate the time, in May, when those particular plants bloom and spring explodes into summer. But more powerful, and imposing, natural features are honoured too.

Perhaps nothing more than Japan's national symbol and tallest mountain. Fuji is venerated by adherents of both Shinto and Buddhism. Even an atheist like me can appreciate its beauty, a beauty which is enhanced, not diminished, by the mist that often surrounds it. If you asked a child to draw a picture of a mountain it's quite likely they'd come up with something not unlike Fuji and it's no surprise that haikus have been written about it.

Basho (1644-1694), the most famous Japanese poet of his era, wrote quite a few about Fuji.

"Chilling autumn rains curtain Mount Fuji, then make it more beautiful to see"

"Misty rain; Today is a happy day, although Mount Fuji is unseen"

"The wind from Mount Fuji, I put it on the fan. Here, the souvenir from Edo"

Perhaps nothing more than Japan's national symbol and tallest mountain. Fuji is venerated by adherents of both Shinto and Buddhism. Even an atheist like me can appreciate its beauty, a beauty which is enhanced, not diminished, by the mist that often surrounds it. If you asked a child to draw a picture of a mountain it's quite likely they'd come up with something not unlike Fuji and it's no surprise that haikus have been written about it.

Basho (1644-1694), the most famous Japanese poet of his era, wrote quite a few about Fuji.

"Chilling autumn rains curtain Mount Fuji, then make it more beautiful to see"

"Misty rain; Today is a happy day, although Mount Fuji is unseen"

"The wind from Mount Fuji, I put it on the fan. Here, the souvenir from Edo"

Mount Fuji

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), possibly Japan's most famous ever artist, lived in Edo (now Tokyo) and he was obsessed with Fuji. He was also obsessed with erotica (we'll come to that later), changed his name twenty times, and moved house an astonishing ninety-three times. But it is for his thirty-six views of Mount Fuji that he is most well remembered. Understandably so, they're incredible.

Diverse, yet stunning, images. Fuji can either be the focus of the print or a mere detail in the background, sometimes difficult to pick out at first. Fuji can either be red hot or caked in snow and ice. People carry out their everyday activities with Fuji looming large in the background and in The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the rogue wave not only renders Fuji a mere detail but almost obliterates, both on the canvas and in real life, two teams of fishermen in their oshiokuri-bune boats.

Hokusai - Thirty-sex Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832)

Hokusai - Thirty-sex Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832)

Hokusai - Thirty-sex Views of Mount Fuji (1830-1832)

Hokusai - Thirty-sex Views of Mount Fuji (The Great Wave off Kanagawa) (1830-1832)

It's a reminder that nature could be destructive as well as beautiful. When, in the twentieth century, Japan set upon a path of rapid modernisation there were attempts to control the awesome power of nature. As cities expanded, roads and railways were cut through the countryside and coastlines were concreted over. Thousands of rivers were straightened, dammed, and lined with concrete.

One theory of how the Japanese, a people who literally worship nature, could allow this to happen is the theory of focus. It posits that the Japanese can look at a beautiful rice paddy, appreciate its splendour while, at the same time, managing to completely ignore a huge ugly billboard that's been erected in the middle of it.

Not all Japanese buy into that. Hiroshi Sugimoto certainly doesn't appear to. His simple, monochrome photographs hark almost back to the era of Toyo and Tohaku and in these photographs the spirit of nature, art, and space combine as if some holy trinity lives on. The shrine he built in Naoshima is based on the holiest place in all Shinto and it too combines a love of the natural with a love of the built environment. It does look a wonderful place for reflection.

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Caribbean Sea, Jamaica (1980)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Bay of Sagami, Atani (1997)

Hiroshi Sugimoto - Shinto Shrine

There's a lot that Japanese people may wish to reflect upon. At 8.15am on the morning of the 6th of August 1945, the US military dropped the first ever atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima killing 70,000 people instantly and all but annihilating the city. It was a terrible event and it had been caused, primarily, by the terrible Japanese decision to throw their lot in with Hitler and Mussolini.

But Japan had seen its cities destroyed before. They'd seen them destroyed but they'd also seen them rebuilt and reimagined. In part two of The Art of Japanese Life, James Fox takes three different cities at three different times in Japanese history (Kyoto, Edo, and Tokyo - now the world's largest urban area) and looks at what they tell us about Japanese life and Japanese culture.

In 796AD on Japan's largest island of Honshu, a party of men were searching for land. They believed their home town was cursed by famine, floods, disease, and murder. They named the place they settled Heian-kyo ("tranquility and peace capital") but it later took the name it still holds today. Kyoto.

But Japan had seen its cities destroyed before. They'd seen them destroyed but they'd also seen them rebuilt and reimagined. In part two of The Art of Japanese Life, James Fox takes three different cities at three different times in Japanese history (Kyoto, Edo, and Tokyo - now the world's largest urban area) and looks at what they tell us about Japanese life and Japanese culture.

In 796AD on Japan's largest island of Honshu, a party of men were searching for land. They believed their home town was cursed by famine, floods, disease, and murder. They named the place they settled Heian-kyo ("tranquility and peace capital") but it later took the name it still holds today. Kyoto.

Kyoto

Kyoto

Kyoto has more UNESCO World Heritage Sites than any other city on Earth. Inspired by Chang'an in China and built on a grid structure (like, centuries later, New York) it was intended as a blueprint for Utopia, a dream realisation of a rational city. But that's easier said than done. The palace of Kyoto burned down fourteen times.

Between infernos the court would enjoy cherry blossoms, moon watching, music, and listening to the chirping of crickets. Murasaki Shikibu, born around 973AD, was a lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court but in her spare time she became something of a star by writing The Tale of Genji. An epic book twice as long as War and Peace that is said to be the world's first novel.

Murasaki Shikibu - The Tale of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu - The Tale of Genji

As well as literature, aesthetics in Kyoto covered painting, poetry, calligraphy, garden design, and even the humble cup of tea. A tea house in Kyoto is devoted to Sen no Rikyu who, along with others, is credited with making tea and its consumption into an art form. It was believed (and I'm not going to doubt it) that you could use tea to rise to a new level of consciousness, that it could wash away the dust in your mind.

These thoughts underpinned the popularity of the Japanese tea ceremony and they (and it) acted as a way of bringing nature into city life. These ceremonies were designed as appreciations of modesty, imperfection, and impermanence. Rikyu felt ceramics were too elaborate so raku pottery was born. A more humbler form that placed the required emphasis on modesty.

Tea House, Kyoto

Raku pottery

This age of reflection was brought to a shattering end in the sixteenth century when civil war arrived in Japan. In 1600 Tokugawa Ieyasu seized power and, as the shogun, established a government in Edo. Previously a run down fishing village that was, every twenty to thirty years, torn apart by fire it seemed an unusual choice for the new capital of Japan but it soon became, with the possible exception of Beijing, the world's largest city.

Foreigners, bar a small number of Dutch traders, were barred from Edo. These regressive measures didn't stop culture thriving but it was a very different culture to that of the court of Kyoto. A culture of puppet shows, courtesans, and gangsters

Kabuki performer

Kabuki performers

The decadent heart of Edo was the Ukiyo-e ('floating world') pleasure district where kabuki performances took place. Performances could last all day so to liven things up the crowds often broke out into scuffles, riots, and stage invasions. The Samurai enjoyed kabuki but soon women joined foreigners in getting short shrift. They were barred from performing and this created a lucrative trade for female impersonators.

For the first time woodblock prints were made in full colour and many commemorated kabuki performances. Kitagawa Utamaro thrived in the half-light of the floating world. Virtually nothing is known of his life but approximately one third of his woodblocks concentrate on the lives of sex workers.

Kitagawa Utamaro - ?

Kitagawa Utamaro - ?

Kitagawa Utamaro - The Poem of the Pillow (1788)

We do know he made The Poem of the Pillow (or Utamakura) in 1788. We can't see either of the horny couple's faces but we can see their buttocks and, more shockingly still to Japanese society at the time, we can see the nape of the female's neck. Then considered more forbidden than genitalia.

Don't worry though. Shunga, for that is the name of these erotic prints, featured plenty of genitals including some frankly enormous cocks. Oh, and an octopus performing cunnilingus because, hey, why not?

Shunga

Shunga

Shunga

If you prefer something a little less explicit then marvel at Hiroshige's wonderful series of views of Edo. They're comparable with Hokusai's views of Mount Fuji from two decades earlier and, in fact, many of them even contain. Fuji. Lakes, trees, the sky, and the moon all join the mountain in a wonderful celebration of both nature and woodblock prints. People, also, are often part of the picture. They're part of nature too.

The styles of Hiroshige and Hokusai gained global popularity when Japan reopened trade routes with the West and soon copies of these prints, along with kimonos, lacquerware, and pottery started making their way to Europe. The art of Manet, Monet, and Van Gogh in particular responded to the art of Japan but it wasn't one way traffic. As Japan changed Europe, Europe in turn changed Japan.

Hiroshige - One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58)

Hiroshige - One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58)

Hiroshige - One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58)

Hiroshige - One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856-58)

From the 1860s onwards in Japan, much old culture was discarded and Edo was rebranded, In 1868 its name was changed to Tokyo. The most noticeable changes, initially, were the construction of European looking buildings like the Akasaka Palace. Akasaka's architect Katayama Tokuma had spent a year in Europe looking at the palaces of France, Germany, and the UK.

The exterior looks a bit like Buckingham Palace but the interior ramps it up. It's ludicrously opulent, festooned with European style paintings, French chandeliers, and Italian marble. Described by Fox, not incorrectly, as "a brazen act of appropriation" (though little different to the way Europeans were orientalising the Japanese), the Akasaka Palace has spent much of its existence uninhabited

Akasaka Palace

Other buildings suffered much worse fates. The 1923 Kanto earthquake killed over 100,000 people in the Tokyo area and then the USAF dropped those bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing half a million more and destroying half of Tokyo. As Japan was rebuilt between 1945 and 1963 the population of Tokyo trebled to ten million and the country experienced unprecedented growth.

Aftermath of 1923 Great Kanto earthquake

Shinjuku

Predictably, some were left behind as the huge temples of commerce began to dominate the Shinjuku skyline. Shinjuku, now Tokyo's commercial and administrative centre, looked like a modern megalopolis full of neon, glass, and steel but between and behind these buildings there thrived, or strived, an underclass. An underbelly if you must.

The founding father of Japanese street photography, Daido Moriyama, used a small portable camera to snap the rootlessness, the darkness, and the hedonism of Shinjuku's side streets. Moriyama's got hair like Johnny Marr and his photos capture the Tokyo streets as well as Marr's music did Manchester in the eighties. Dark, blurred, slightly out of focus - they have the feel of someone wandering through the city in a daze trying to make sense of it all. Half awed and erotically charged, half disgusted and desperate.

Daido Moriyama - ?

Daido Moriyama - ?

Daido Moriyama - ?

Daido Moriyama - Farewell Photography (2006)

A feral street dog looks back at the photographer as if to represent all those left on the street as the economic miracle peaked in the eighties. Japan, by then, the world's second largest economy. Moriyama seems to have tapped into something from both the past and the future. The Japanese obsession with destruction and reconstruction.

In the 1988 anime film Akira (dir:Katsuhiro Otomo), Tokyo is both a neon dream and a neon nightmare and is, of course, razed to the ground. The same year saw Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies in which the director drew on his own experiences of WWII, aged nine he survived (with his family) a major US air raid on Okayama.

Akira (1988)

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

These earthquakes, bombs, and air raids were incorporated into much of Japanese culture but as time passed, a more stable Japan saw a world of design and high commerce propser. A world of Muji, Issey Miyake, J-Pop, Ryoji Ikeda, and, most of all (suggests Fox), Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama - ?

Yayoi Kusama - ?

Yayoi Kusama - ?

Yayoi Kusama - ?

Kusama has her own very unique spin on Pop Art, all polka dots, coloured lights, and mirrors. It's very much of the 'zeitgeist' and it's very much Instagrammable. I hardly ever even look at my Instagram account but during a visit to the Broad Gallery in Los Angeles back in 2016 I found myself, quite happily, in one of her artworks and I once joined a very long queue of eager art hipsters on City Road to enter one of her exhibitions. Our guide James Fox sees, not unfairly, Kusama's artwork (and Japan itself) as an 'infinite metropolis'. Japan, he contends, is an artwork of its own creating.

It's a country where you can 'eat with your eyes'. Much of domestic life is informed by aesthetics so why should your lunch be any different. Lovingly curated bento boxes contain rice, noodles, fish, meat, and pickled vegetables and are often themed. Unsurprisingly the spring themed bento proves a particular favourite.

Bento box

Minka in Miyama

Bento boxes are popular far beyond the shores of Japan now and Japanese architecture, too, has had a huge influence on the planet. Frank Lloyd Wright was a big fan and incorporated many ideas from Japan into his buildings. With 127,000 people crammed into its densely populated, and vast, cities it's not a shock to learn that many now live in small flats.

But that's not always been the case. Just a century ago 85% of Japanese lived in the countryside. Many in vernacular houses called minka. These days only a few remain. Minka were designed to cope with the extreme (at either end) temperatures that Japan has and also built mainly of wood - which brought with it the fairly obvious problems of living in a wooden house in a forested area that can suffer extremely hot summers.

But stone buildings brought worse problems. Not least the chance of being crushed to death following one of Japan's, quite common, earthquakes. Whole houses were made without the use of screws, nails or even glue. Shinto demanded that wood be treated with reverence. Hammering a nail into it would be disrespectful.

On the outskirts of Yokohama, built in 1649, stands Rinshunkaku. Built by the samurai lord Tokugawa Yorinobu for relaxation and reflection. A holiday home, basically. It's very different to the Baroque palaces going up around Europe in the 17c and it's beautiful both outside and in. Inspired by Zen Buddhism, it has an open plan with no clutter, paper walls, soft light, and rice straw mats on the floor.

But that's not always been the case. Just a century ago 85% of Japanese lived in the countryside. Many in vernacular houses called minka. These days only a few remain. Minka were designed to cope with the extreme (at either end) temperatures that Japan has and also built mainly of wood - which brought with it the fairly obvious problems of living in a wooden house in a forested area that can suffer extremely hot summers.

But stone buildings brought worse problems. Not least the chance of being crushed to death following one of Japan's, quite common, earthquakes. Whole houses were made without the use of screws, nails or even glue. Shinto demanded that wood be treated with reverence. Hammering a nail into it would be disrespectful.

On the outskirts of Yokohama, built in 1649, stands Rinshunkaku. Built by the samurai lord Tokugawa Yorinobu for relaxation and reflection. A holiday home, basically. It's very different to the Baroque palaces going up around Europe in the 17c and it's beautiful both outside and in. Inspired by Zen Buddhism, it has an open plan with no clutter, paper walls, soft light, and rice straw mats on the floor.

Rinshunkaku

Rinshunkaku (interior)

Ma is a Japanese concept that celebrates the space in between things. Be that the emptiness of rooms or the silence between sounds. Charles and Ray Eames, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius, like Lloyd Wright, were all inspired by this graceful concept and the fantastic buildings it helped create.

One place in the Japanese home was reserved for extravagance (relative extravagance, very relative extravagance) and decoration. The tokonama is a built in recess where scrolls and floral arrangements are displayed for artistic appreciation. It's both a hobby and a highly personal form of expression.

The floral arrangements are known as ikebana and there are over one thousand schools in Japan today dedicated to this art, an art that had begun in a Buddhist temple in Kyoto as far back as 1462. Ma, when applied to ikebana, refers to the space between the branches and there are quite specific guidelines on how the viewer looks at ikebana!

One must sit face to face with the ikebana and be fully composed before beginning by looking at the base of the plant (the origin of life) and then following the line of the plant(s) upwards. Finally, readjusting one's focus and taking in the ikebana in its entirety. It is, of course, a hugely meditative process. One it would do many of us no harm to take some time out for now and then.

One place in the Japanese home was reserved for extravagance (relative extravagance, very relative extravagance) and decoration. The tokonama is a built in recess where scrolls and floral arrangements are displayed for artistic appreciation. It's both a hobby and a highly personal form of expression.

The floral arrangements are known as ikebana and there are over one thousand schools in Japan today dedicated to this art, an art that had begun in a Buddhist temple in Kyoto as far back as 1462. Ma, when applied to ikebana, refers to the space between the branches and there are quite specific guidelines on how the viewer looks at ikebana!

One must sit face to face with the ikebana and be fully composed before beginning by looking at the base of the plant (the origin of life) and then following the line of the plant(s) upwards. Finally, readjusting one's focus and taking in the ikebana in its entirety. It is, of course, a hugely meditative process. One it would do many of us no harm to take some time out for now and then.

Ikebana

Ikebana

Ikebana

The calligraphy that makes up the tokonoma takes many forms. One, shodo, resembles (to an untrained eye such as mine) the paintings of Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. We see Tomoko Kawao making one and, again, her technique is not so different to that of Pollock. She certainly put a lot of effort and energy in to it. She looked like she needed a nice relaxing cup of ceremonial tea once she'd finished.

Shodo

Tomoko Kawao - Shodo

Kawao is keeping old traditions alive (and investing them with new blood) but, elsewhere (even as other Asian tourists play act in kimonos in Kyoto) native Japanese traditions are under threat. The celebrated Japanese architects Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito, and Kengo Kuma were, despite keeping some traditional Japanese ideas, more celebrated for their modernity and their internationalism than their predecessors. Their works a rather splendid mix of Zen and minimalism.

Zenimalism they called it (of course they did) and it was exported to the world! Toyo Ito built the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in 2002. The average Japanese person, however, could not expect to live in a building designed by Ando, Ito, or Kuma. In fact, the average Japanese home these days lasts only thirty years before it is torn down. Inheritance tax is so high it's often cheaper to bulldoze the family home and start again. Couple that with Japan's relaxed planning regulations and you can see why Japan has more architects per capita than any other nation on Earth.

Tadao Ando - The Church of the Light (1989)

Toyo Ito - Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (2002)

Kengo Kuma - GC Prostho Museum Research Center (2010)

'Zenimalism' was for the rich but since 1980 Muji has made Zen design more affordable to everyone. They've made it 'off the peg'. You can buy, in their stores, anything from stones to sofas to aromas. You can buy some Zen - which hardly seems the point - and isn't. Muji is about as realistic a Japanese experience as Laura Ashley is a British one. It's a Japanese experience but it's hardly the Japanese experience.

Muji

Kyoichi Tsuzuki - ?

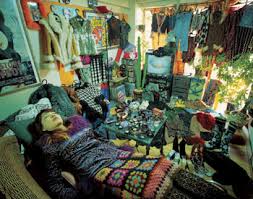

The real Japan is full of clutter, strewn with power cables and with often limited space available for Tokyo's citizens it demands both experimentation (some flats have no windows, others no walls, concrete and post-modernism designs dominate) and inventive use of storage. Photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki rebelled against the idea of Japanese Zen and compartmentalism by producing photographs of the young people of Tokyo crammed into their tiny apartments stuffed full of 'storage'.

Often the residents of the blocks seem like little more than storage themselves but in other instances these cramped spaces have been personalised to a wonderful degree. There's no space for ma in these apartments, no space for space, but the inhabitants have still given them a personal flourish.

Kyoichi Tsuzuki - ?

Kyoichi Tsuzki - Tokyo a certain style (1999)

Kyoichi Tsuzki - Tokyo a certain style (1999)

Traditionally minded critics complain that these living quarters show everything that is wrong with modern Japan but Tsuzuki disagrees. He says rich people's house are boring and say more about their decorators and their architects than those that dwell in them. Eventually they all start to look the same.

In 1999 Tsuzuki produced a series called 'Tokyo a certain style' in which he removed residents from their flats but still created portraits of them just by showing their empty rooms. Full of clutter - yes - but full of character - also.

Architect Terunobu Fujimori could not be accused of lacking character. His creations appear bizarre at first sight and, to be fair, some of them are. Fujimori wanted to channel Japan's prehistoric past. He put dandelions on the walls and roof of his own house. Other, later, houses saw leeks and grass growing out of them (ideas that have been widely copied following initial bemusement).

Terunobu Fujimori - ?

Terunobu Fujimori - ?

Terunobu Fujimori - Dandelion House

His Too High Tea House looked out to magnificent views of the mountains AND the city but he wasn't just looking out to nature, he was bringing nature into the home, a home in the city, and, therefore, Fujimori's were the ideal creations to end a wonderful, informative, and strangely relaxing series with. He combined nature, the city, and the home (as did the series) in a whole that at first appeared odd but with closer scrutiny proved to make a very beautiful kind of sense.

If I ever get to visit Japan that's exactly the sort of experience I'll be looking for. Sayonara!

Terunobu Fujimori - The Too High Tea House

No comments:

Post a Comment