"It's not what you are that counts. It's what they think you are" - Andy Warhol

Campbell's soup, Brillo pads, Burger King, Coca-Cola, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, race riots, suicide, and the electric chair. Andy Warhol gave Americans what they already had but, for some reason, were unable to see clearly, It took Warhol, like so many Americans the son of immigrants, to look at all these things with fresh eyes and it didn't matter, least of all to him, if he glorified or critiqued America. He simply showed America to America.

Soup Cans (1962)

In Andy Warhol's America (BBC2/iPlayer) we get a look at both Warhol's life and career and one at how that reflected American society. It's a story that takes in a huge large of contributors (artists, writers, "superstars", mentors, gallerists, poets, art dealers, friends, collaborators, photographers, former police chiefs, Warhol's biographer, Warhol's nephew, Jerry Hall, Eve Ensler, Larry Gagosian, Bianca Jagger, and even Burger King's Head of Global Marketing) and is soundtracked, as you'd imagine Warhol would have approved of, by a range of pop music from different eras:- Shirley Temple, Dr John, Lene Lovich, The Cars, The Temptations, Magazine, Suicide, The Velvet Underground (of course), Sylvester, MIA, China Crisis, and New Young Pony Club with special mentions for both Donna Summer's Love's Unkind and Lou Reed and John Cale's Small Town.

Oh, and there's even time for a quick run through of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer which was good because I watched it over Xmas. Warhol was born in Pittsburgh. In 1928, in the black and white days, to Slovak immigrant parents. Pittsburgh was a city of fire, of smoke, of furnaces, and of industry. Soot fell from the sky all day and all night long. It was not the American Dream that Andy Warhol wanted.

So he got out of Pittsburgh and moved to New York in 1949. As a promising, and humorous, illustrator New York was a good place to be. It was also a good place to be an artist and an exceptionally good place to be a queer artist. On Madison Avenue, he made himself rich with illustrations, especially of shoes, but the money wasn't making him happy.

He couldn't get laid, he constantly felt betrayed, and be began to feel so low that he could sometimes not be left on his own. He refused to hide his homosexuality and, in fact, flaunted it by painting (not for the last time) huge dicks, sometimes with ribbons wrapped round them as if to signify they were gratefully received gifts.

Penis (1977)

Five Coke Bottles (1962)

In 1962, he painted an image of a Coke bottle and, eventually, mass reproduced silk screens of that Coke bottle and indeed multiple Coke bottles. Next up it was the infamous Campbell's soup cans. To Warhol, and to his family, these products symbolised freedom from labour, they symbolised not being poor. They were part of the American Dream he so lusted after.

But more even than Coke bottles and soup cans, that was personified in the form of Marilyn Monroe who died, aged 36, in 1962. Warhol, of course, made Marilyn the subject of his art - time and time again.

Marilyn Monroe (1967)

It's possible that Warhol even, in a way, identified with Monroe. She'd had 'work' done and so had he. There was also the wigs he'd wear. It's possible that Andy Warhol's greatest ever artwork was himself. He was ever keen to keep an air of mystery about himself as it helped keep that profile up. We see him on a television chat show refusing to speak and instead whispering his answers into the ear of Edie Sedgwick who replies to questions on his behalf.

By the mid-sixties Pop Art was huge and Warhol was the face of the movement, he was its most famous proponent. He used his commission at the New York's World's Fair to add silk screens of the thirteen most wanted criminals in America to Philip Johnson's New York state pavilion. Much to the anger of New York governor Nelson Rockerfeller.

13 Most Wanted Men (1967)

"Everything is beautiful" - Andy Warhol

Electric Chair (1964)

Warhol didn't differentiate between that which might please and that which might offend. To him it was all part of the big American picture. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Vietnam, and dogs set on black people in Birmingham, Alabama (in which he uses, as source material, Charles Moore's photos from Life magazine). He described electric chairs as "beautiful" (if "everything is beautiful then surely that includes execution devices?) and made art of the one from Sing Sing prison where the Rosenbergs were executed in 1953.

Violence hadn't gone away in America since then but it never seemed clear exactly what, if anything, Warhol was saying about it all. In works like Pink Race Riot (and Mustard Race Riot), some felt him to be supportive of the civil rights movement. Others felt he was simply exploiting it to promote himself and his art.

Race Riot (Pink) (1964)

Race Riot (Mustard) (1963)

Twelve Jackies (1964)

Following John F Kennedy's assassination in Dallas in November, 1963, Warhol turned his attention to JFK's widow Jackie in works like the following year's Twelve Jackies but then he turned inwards, at least by his standards, and instead of looking out at the world he had the world, or at least what he saw as the world that mattered, come and visit him at his Silver Factory.

There he did 'screen tests' for the likes of Lou Reed, Bob Dylan,

Dennis Hopper, and

Salvador Dali as well as local drug dealers and pimps. They also played Russian roulette and did A LOT of drugs there (one man ended up living in the toilet) but that hardly made them stand out in American society during that era as, by 1967, it was estimated that 31,000,000 Americans were on amphetamines.

"Buying is more American than thinking" - Andy Warhol

Out of the Silver Factory, or simply Factory, sprang The Velvet Underground, the band Warhol turned into his own studio band but who would have been nothing without the songwriting genius of Lou Reed and

John Cale. It was Warhol, though, who brought Nico in and it was Warhol who got The VU to play a gig at a psychiatrist's convention.

Something I'd like to have witnessed! Continuing to expand his remit, Warhol began to make experimental films. The Chelsea Girls was nearly four hour longs, Tub Girls featured young girls in the bath with their boobs out, and both Sleep and Blow Job are pretty self-explanatory.

Chelsea Girls (1967)

Tub Girls (1966)

Sleep (1964)

Blow Job (1963)

They were pretty much unwatchable and they were certainly, defiantly, uncommercial. The whole scene around the Factory, those there report, was 'vicious', 'competitive', and even 'coercive'. In some ways it comes across as a precursor to reality TV as volatile people desperate for fame, for meaning in their life, compete for attention.

With that already toxic atmosphere and then the introduction of ever stronger drugs the inevitable happened and there was a suicide. Warhol was so upset that he refused to talk about it but it wasn't just Warhol who was upset, some people were upset with Warhol.

Not least Valerie Solanas. She had strong ideas about Warhol just as she had strong ideas about all men. As the author of the SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto, she'd written a script called Up Your Ass and given it to Warhol to have a look at with the idea that he might be able to make a movie of it. He was a busy man and hadn't got round to it. Even going so far as to mislay it. So she shot him.

"The idea is not to live forever. It is to create something that will" - Andy Warhol

A five hour operation saved Warhol's life but he remained weakened for years after. Possibly for the rest of his life. The man who had almost celebrated death had nearly experienced it first hand for himself and he began to move away from the freak scene and into the safer folds of high society.

Though not necessarily because of the shooting. But because he was becoming more business like. Because the world was becoming more business like. Warhol started to make what they called "business art". Which, of course, sounds rather terrible - and much of it was.

But not all of it. Warhol's first major series since being shot was inspired by President Nixon's visit to China to meet Chairman Mao. Warhol, of course, painted Mao and some of the paintings were big - 12/13ft tall - as if to echo the huge portraits of Mao that could be found around Beijing's Tiananmen Square.

Mao (1973)

Warhol's portraits were, however, a little camper than those endorsed by the Chinese state. As the 70s and 80s rolled on, much of Warhol's work was made on the advice of his dealers and was made, quite simply, to make money for them and him.

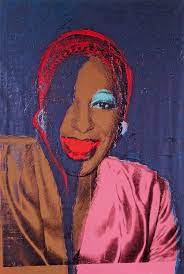

But, again, not all of it. Warhol started to paint drag queens (including Wilhelmina Ross in the Ladies and Gentlemen series) who, back then, were marginalised even within the gay community, he painted the Native American sovereignty movement, its leader Russell Means, and the occupation of Wounded Knee in South Dakota, and he hung out in Studio 54 but, by most reports, he never danced. He did business and by that we're not talking 'rough trade'.

He loved the 'immortality' that fame appeared to give a person but he knew that though his art would be able to live on he would one day die. As he aged he painted what are described as a Hallowe'enish self-portraits including the below one from 1986.

Warhol, of course, had no babies, no children, but the art he left us perhaps acts as enough of a legacy as it is. On top of that, it seems to me that we are, all of us, now - with our obsession with celebrities and labels and our gawping fascination with death and violence, very much Warhol's babies anyway. He saw that long before the rest of us.

No comments:

Post a Comment