Pain, anger, fear, loneliness, anxiety, dread, broken heartedness, internal bleeding, and external bleeding. None of these things are specifically female, everyone can suffer them, but the Royal Academy's current show, Tracey Emin/Edvard Munch:The Loneliness of the Soul, looks at all these things through a distinctly female perspective.

Through a female lens. Specifically, that of Tracey Emin. Though Munch is billed co-headliner, make no mistake - Emin's the star here. The view of Munch we get is an Emin's eye view of Munch and it's a very favourable one. Emin, who was born in 1963 - a full century after Munch, has always cited Munch as a huge inspiration on her work and a fellow traveller when it comes to creating art that explores the complexities of the human condition, art that interrogates the emotional landscape of our souls.

Edvard Munch - Consolation (1907)

Tracey Emin - Ruined (2007)

Unlike other observers of Munch's art, Emin believes his work shows deep respect for women. Hell, sometimes they're even allowed to wear clothes. But not often. The Loneliness of the Soul features nude after nude after nude. By the end of the show I was almost bored of tits. I didn't even think that was possible.

I am, of course, being facetious. The necessity of taking an online virtual tour of the exhibition (accompanied by some rather intrusive muzak) meant my 'visit' to the RA was neither as extensive nor as 'real' as I would have liked. But it was long enough for me to gather that the themes that Emin works round, heartache, blood, and the damage done to our bodies and souls by this thing we call life, are the very themes she sees, quite correctly, in Munch's work.

Tracey Emin - You Were Here Like The Ground Underneath My Feet (2016)

Edvard Munch - Seated Female Nude With Blue Stockings (1919-24)

Edvard Munch - Reclining Female Nude (1917-20)

We are all, after all, damaged goods - and both Emin and Munch articulate that with a deeply held passion. But while Munch looks on it, a curious if emotionally invested bystander, Emin lives it. Munch may be the more accomplished technical artist, it'd be hard to make a claim otherwise, but the personal experience Emin brings to bear on her work ensures, in this show at least, she is his worthy equal.

Munch's reclining and seated nudes are Fauvist explosions of colour, almost soft in focus, whilst Emin's self-portraits are scratchy, scribbly, and possibly in some form of deep emotional trauma. Often they are menstruating or suffering some other deeply personal physical privation. To turn this into art would, if about the other, run the risk of lacking dignity but to make this art about yourself is to invert the shame that women are made to feel about their bodies and imbue them, faults and all - no body is perfect, with a cautious pride.

Tracey Emin - Because You Left (2018)

Tracey Emin - My Cunt Is Wet With Fear (1998)

Tracey Emin - There Is Nothing Left But You (2013)

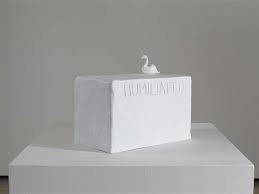

Tracey Emin - Humiliated (2013)

These drawings are among Emin's best work but, at the RA, she lets us know she's no one trick pony. There's no unmade bed but there's neon lit works (My Cunt Is Wet With Fear is, for sure, an arresting title but these works have been so overdone they start to look tired) and there are rectangular white bricks etched with slogans like There Is Nothing Left But You and Humiliated and topped either with de Chirico style mannequins or displaced swans.

Emin does, I suspect, have a tendency to let her titles do a lot of the heavy lifting but that's not necessarily a problem. They're not didactic. They don't tell you what to think of the art. They give you a gentle nudge in the direction of that but, more so, they encourage you to adopt a certain emotional state before you take the work in.

Munch does this with colour rather than words. Model By The Wicker Chair features a rolled up rug of red, a shock of purple hair, and further purple in the mirrored reflection. The room, and the painting, almost throbs with pent up energy. It's both erotically and emotionally charged. Weeping Woman, on the other hand, uses muted greys and browns to produce a more sombre and reflective portrait. This is not a sexualised sitter but one that needs looking after.

Edvard Munch - Model By The Wicker Chair (1919-21)

Edvard Munch - Weeping Woman (1907-09)

Edvard Munch - The Death Of Marat (1907)

Edvard Munch - Women In Hospital (1897)

Tracey Emin - It Was All Too Much (2018)

No comments:

Post a Comment