Pierre Bonnard appears to have lived something of a charmed life. A life of naked women, red wine, dining in front of panoramic views of the south of France, and, most of all, colour. Greens, blues, oranges, reds, purples, any colour you want as long as it's not black. As long as it's bright, bold, and, at the same time, both redolent of nature and, yet, almost completely full of unnatural light. For Pierre Bonnard, it seems, colour was a substitute for light. Perhaps it's why so many paintings, instead of being traditional landscapes, feature windows open to reveal landscapes.

While Tate Modern's concurrent exhibition of Dorothea Tanning paintings drills down deep on her fascination with doors, the Bonnard show features a remarkable amount of windows. In fact there's nearly as many windows as there are paintings of naked women - and there are a lot of paintings of naked women. They don't seem to me, a man, as prurient as the wank fantasies of Edgar Degas or even as titillating as the high end grot of Louis-Leopold Boilly and they certainly aren't as problematic as Gauguin's latent, sometimes blatant, celebrations of paedophilia.

Open Window Towards the Seine (Vernon) (c.1911)

Man and Woman (1900)

Sometimes there's a naked man in them too so it all looks very consensual, sensual even. 1900's Man and Woman shows Bonnard and his girlfriend Marthe de Meligny. Girlfriend, not wife - they were bohemians and this painting shows it. They met in 1893 and did not marry for another thirty-two years.

It's gorgeous too. Saturated with dimmed lights and warm reds. It looks quite a blissful scene. In Young Women in the Garden, de Meligny has been relegated to a vague profile on the right and the centre space of the dazzling orange and candy striped painting features Renee Monchaty whom Bonnard had been having an affair with. It's not clear if de Meligny was aware of Bonnard's involvement with Monchaty but. again, bohemianism!

Young Women in the Garden (1921-3/1945-6)

In the Bathroom (1907)

Sometimes it's all boobs, legs, and bums - quite often women washing and dressing which is both more natural than the contrived forms other artists would use and also a bit more erotic. At the same time the occasional work can give Bonnard the air of a peeping Tom. The curators of Tate Modern's retrospective claim these casual non-poses reflect Bonnard's interest in photography which they may well do but they also suggest a full and open appreciation of the unclothed female form.

At the same time he imbues the painting of jugs (not those ones) and bowls with all the gravitas and patience of a Chardin or a Morandi. A simple cup of coffee on a red and white checked tablecloth can be as heavy with sexual tension as a woman towelling herself off in her boudoir.

Mirror above a Washstand (1908)

Coffee (1915)

Dining Room in the Country (1913)

Dining Room in the Country shows Bonnard's appreciation of the landscape around his house in Normandy, The Mantelpiece manages to get two nudes in for the price of one (one admittedly a reflection) and was so important to Bonnard he chose to show at two prestigious international exhibitions (in Pittsburgh and Venice), while Lane at Vernonnet and Town in South France are perhaps more typical of earlier Impressionist painters like Pissarro and Sisley than Bonnard's own generation.

The Mantelpiece (1916)

Lane at Vernonnet (1912-14)

Town in South of France (Saint-Tropez) (1914)

View from Uhlenhorst Ferry House on the Outer Alster Lake with St.Johannis (1913)

Bonnard liked to capture bustling crowds as much as he did intimate moments. His brushwork had an energy that gave those crowds that bustle. He travelled to Hamburg with his friend, and fellow painter, Vuillard at the invitation of Alfred Lichtwark, the Director of the Kunsthalle,and infused northern Germany with the light he'd filled his native France with.

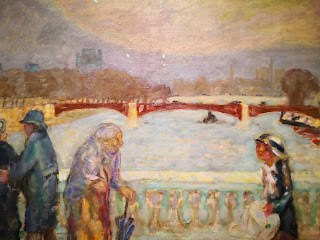

More even. The Pont de la Concorde in Paris looks positively gris in comparison to his Hamburg work, the pedestrians crossing it hunched and beaten down. It's quite an outlier. More typical is the loving Donkey in the Garden; Le Grand Lemps showing the family home in the Dauphine. Each summer Bonnard would revisit for family holidays and, of course, a bit of painting. The tranquility seems incongruent when you consider that the horrors of World War I were taking place only a few hundred miles away at the time.

Pont de la Concorde (1913-15)

Donkey in the Gardens; Le Grand-Lemps (c.1917)

A Village in Ruins near Ham (1917)

That's not to say Bonnard was ignorant of, our chose to ignore, events at the time. A Village in Ruins near Ham could be by a completely different painter. Gone are the life affirming colours, replaced by rust browns and muted pale blues. An overcast sky possibly the strongest hint of all that all was not well in Europe.

For sure, it's another outlier. As soon as Bonnard had visited the war zone near Ham he started work on Summer which is either an expression of his longing for peace and safety or informed by a simple relief to be away from death and destruction and back in the comfort of nature.

Summer (1917)

The Checkered Tablecloth (1916)

The Fourteenth of July (1918)

Bathing Woman, Seen from the Back (c.1919)

Nude Crouching in the Tub (1918)

The Bowl of Milk (c.1919)

House among the Trees (1918)

Piazza del Popolo, Rome (1922)

He even travelled to Rome where he painted a very pinkish picture of the Piazza del Popolo. His passion for nature, and for colour, was back and it didn't matter if it was something as humble as a basket of bananas or as awesome as a Mediterranean landscape. Even a fence. 1923's The Violet Fence certainly lives up to its name. The uneven fence posts are a joy but so is everything else in the painting. The medley of leaves, the yellowing sky, and even the brown of the wood on the trees.

Basket of Bananas (1926)

Landscape in the South of France (1920-1)

The Violet Fence (1923)

Terrace in the South of France (c.1925)

The Window (1925)

Terrace in the South of France gives so much of the canvas over to a sun bleached wall that it borders on abstract expressionism, The Window looks out at an unnamed city and seems to have something of the Cezanne or the Van Gogh about it, the blocky houses almost stepping stones towards Cubism, whereas 1925's The Bath seems harsher, more mortal, and more corporeal than many of Bonnard's nudes. It's almost a precursor to the portrait paintings of later British artists like Lucian Freud, Euan Uglow, and William Coldstream.

The Bath (1925)

Landscape at Le Cannet (1928)

Standing Nude (1928)

The show repeats itself with yet more lovely landscapes and nubile nudes yet it never becomes boring. Each painting is a pleasure in its own right, it's hardly a surprise that the curators at Tate Modern were encouraging 'slow viewing' of the show. 1931's The Boxer is a rare self-portrait and odder still when you consider that Bonnard seems to have defined himself much more a lover than a fighter.

Equally peculiar, Bonnard looks uneasy. Quite a different image, a changed perspective, from the younger, carefree, man we thought we knew earlier. Now in his sixties, Bonnard was getting old and finding more time for self-reflection. He'd been called "a painter of happiness" but had replied that "he who sings is not always happy".

Yet his art continued to inch forward. The irregular composition suggests the sexagenerian sex addict was keeping abreast of new developments in the art world. Note how the model is offset to the right of the painting as the flowers and the mantelpiece take centre stage. Bonnard, it seems, clearly was one who DID look at the mantelpiece when he was stoking the fire.

Yet his art continued to inch forward. The irregular composition suggests the sexagenerian sex addict was keeping abreast of new developments in the art world. Note how the model is offset to the right of the painting as the flowers and the mantelpiece take centre stage. Bonnard, it seems, clearly was one who DID look at the mantelpiece when he was stoking the fire.

The Boxer (1931)

Nude in the Mirror (1931)

Flowers on a Mantelpiece in Le Cannet (1927)

Nude in an Interior (c.1935)

A similar trick was repeated, and improved upon, in 1935's Nude in an Interior - and now Bonnard was bringing mirrors into the equation to add unusual angles and perspectives. The colour continued to intensify and become ever less realistic (see Large Dining Room Overlooking the Garden) in some paintings while in others, like In the Bathroom, he'd pared down both the brightness, the contrast, and even the components of the painting. It's just a few cupboards, an old unvarnished wooden door, and some fading paint and yet Bonnard makes this as beguiling to the eye as an ultramarine dining room looking out to a deep blue sea.

Large Dining Room Overlooking the Garden (1934-5)

In the Bathroom (c.1940)

Marthe de Meligny died in 1942, Renee Monchaty had taken her own life in 1925, leaving Bonnard without his long term companion(s), World War II had broken out, and Bonnard was reaching the end of his life. He would die in the French Riviera in 1947 aged 79 but even in his final years he was still consumed by, and still had daily encounters with, nature.

The steps in his garden gave him solace and provided him with subject matter and in the last year of his life he made his final painting, Almond Tree in Blossom (which is also the final painting of this exhibition), of the view from his bedroom window. Too weak to change the colour of a patch of ground he got his nephew, Charles Terrasse, to do it for him.

It's a frail, skeletal painting by Bonnard's standards. In that it possibly reflects his own physical deterioration but in its love of nature and its passion for colour it is wholly typical of his work. Pierre Bonnard had lived, loved, travelled, and seen two world wars in his lifetime but in his dying days it was the nature that he came from and the nature he was soon to return to that remained, as ever, his over-riding passion. What a wonderful artist. What a gorgeous show.

Steps in the Artist's Garden (1942-4)

View of Le Cannet (1927)

Almond Tree in Blossom (1946-7)

No comments:

Post a Comment