"White's gonna take control" - White, Birdland.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler's Thames nocturnes are among my favourite works of art in all the world. James Abbott McNeill's Whistler more famous Woman in White is not. But there is one thing that the two of them very much have in common and the clue comes in the title that Whistler gave to the below painting of his lover Joanna Hiffernan.

Symphony in White, No. 1:The White Girl (1861-72)

Symphony in White No. 1! It sounds a bit formal, doesn't it? I'm sure that to be described as a symphony is very romantic but I think Whistler's reason for choosing that name isn't entirely down to his feelings of love for Hifferman. Instead, Whistler is, in his strangely modern way, trying to show that figurative art can also have abstract qualities.

It can be as much about the paint as it is about the sitter. Or, for that matter, river. Hiffernan seemed to understand and appreciate this. She said of the painting:- "some stupid painters don't understand it at all" before adding that "Millais, for instance, thinks it splended, more like Titian and those old swells than anything he has seen".

Jim, as Hiffernan refers to Whistler, was worried that "the old duffers" at The Royal Academy may refuse it altogether and that's exactly what they did. It eventually hung at Salon des Refuses along with other rejected artworks. But now it's back at the RA and it's the central piece of an exhibtion, Whistler's Woman in White, that is entirely dedicated to it.

Purple and Rose:The Large Leizen of the Six Marks (1864)

Or at least purports to be. There a few tenuous links and the odd curveball has been included to flesh the show out but overall the curators have done a good job of showing how a work that perhaps looks unremarkable to our modern eyes was once considered (almost) shocking. It also delves back into Whistler's life, Hifferman's life (though less so - she was, of course, primarily a "muse"), and the general milieu of the time as well as how other artists interacted with, copied, or riffed on Whistler's Woman in White.

I've included names of the artists beneath the images when possible. If there is none, that means it's a Whistler. The exhibition also includes pretty much every known image of Hifferman but either they or, more likely, Wikipedia are wrong about something. The RA say Hifferman died prematurely in 1886 (she'd have been in her early forties) while the free encyclopedia says she lived until 1903. If that's correct she died the same year as Whistler who was nine years her senior.

The exhibition claims she was born in 1839, Wikipedia goes for 1843, but what seems to be certain is that she was born and baptised as a Catholic in Limerick but moved, with her family - at a young age - and along with thousands more poor Irish immigrants, to Victorian London. Whistler was an immigrant too, but a rather different one.

He'd come, via Paris - where he studied art, from Lowell, Massachusetts. When Hifferman was in her late teens, and Whistler his late twenties, they met on Rathbone Place and she became his friend, his lover, and his confidante. Friends remarked he could not do without her.

Purple and Rose, from 1864, shows Hifferman as both artist and merchant. Though she seems to have been made up to look more Chinese (different times) the painting is intended as much to show off her intelligence and artistic curiosity as it is her beauty. Although, more than anything it is intended to show off Whistler's skill as an artist. Of course it is.

Utagawa Hiroshige - Etchu Province, Toyama, Pontoon (1853)

Utagawa Hiroshige - Suruga Province:Miho Pine Grove (1853)

Unknown - Plate (1662-1722)

There's some lovely Japanese prints, including some from Hiroshige, and Chinese porcelain on loan from the V&A and the Hunterian in Glasgow so we can see the sort of stuff that was inspiring and influencing Whistler and his fellow modernists at the time (the three above items were all, at one point, owned by Whistler) and there's an image Whistler painted of himself in his studio with Hifferman posing, and looking tired, in a white dress.

The figures appear natural, as if unposed, but Whistler could not but help include a little bit of Japonisme in the form of the unnamed woman's fan. It's believed to be inspired by Diego Velazquez, specifically his 1656 painting Las Meninas, which makes for a neat link with Francis Bacon whose Man and Beast exhibition was showing downstairs while I visited the Whistler show.

Whistler - The Artist in His Studio (1865-1895)

Sea and Rain (1865)

I'd be back to look at the Bacon soon enough. He's another favourite of mine. But, for now, my mind was turned to yet another artist I'm an admirer of. I can't help that thinking man of Whistler's coastal paintings have something of the Turner about them. Like Turner, you can almost feel the refreshing droplets of sea water in the air, the gentle breeze, and the feeling of satisfaction, possibility, and awe you get when you stare out into the endless sea.

It's as if Whistler was the (not so) missing link between Turner and the later Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters. His landscapes don't aim for the dramatic. They are dramatic already so can just be. The music I put on to write this blog is by Debussy and I can recommend it should you be one of the few people who bother to read it.

Low Tide at Trouville (1865)

Calm Sea (1866)

Green and Grey:Channel (The Sea) (1865)

Gustave Courbet - Jo, la belle Irlandaise (1865-66)

The paintings of Trouville in Normandy were created when Whistler and Hifferman were staying with the Realist French painter Gustave Courbet and though Courbet also painted the sea, he seemed even more enamoured with Hifferman whom he called a "superb redhead". In a letter to Whistler, more than a decade later, he wrote:-

"Do you remember Trouville and Jo who played the clown to amuse us? In the evening she sang Irish songs so well because she had the spirit and distinction of art. I remember the hotels by the sea where we took baths in the icy water and the salad bowl of prawns in fresh butter without counting the cutlet at lunch. I still have the portrait of Jo which I will never sell. Everyone admires it".

Steady on, old boy! Though Courbet's painting of Hifferman, in light of his later quote, seems a little lustful, Whistler's feel more loving. More tender. If, because of their technical nature, strangely removed at times. You can even see, as the years go by, that the paintings of her start to feature ever more expensive looking accoutrements in the background. Whistler having moved to Chelsea during this period.

Symphony in White, No.3 (1865-67)

The Royal Academy began to accept his work but it's not sure if they'd come round to his artistic vision of if they'd mistakenly thought there was some link between Whistler's painting and Wilkie Collins's recently published 'sensation' novel The Woman in White.

Whistler was adamant in his denial:- "I had no intention whatsoever of illustrating Mr Wilkie Collins's novel. It so happens, indeed, that I have never read it. My painting simply represents a girl dressed in white standing in front of a white curtain". The publicity did him no harm though. But it's quite different to Frederick Walker's dramatic gouache (below) that was made to advertise a play based on Collins's' book that was shown in London in 1871.

Frederick Walker - The Woman In White (1871)

Weary (1863)

The Boy (Charlie Hanson) (1875-76)

James McNeill Whistler's last will and testament (1866)

As if to thank Hifferman for her role in his success, Whistler (on his mother's advice) amended his will to leave everything to her when he died - and then he shot off to Chile. For some unexplained reason - but one that left her in charge of his affairs while he gallivanted around South America.

Whistler and Hifferman never married so this event does mark a significant commitment on both their parts. There's a small portion of the exhibition given over to paintings that Whistler made of London in the 1860s, particularly around the docks in the East End - where he lived before moving out West, which give you a feel for what Whistler and Hifferman's life in the city was like.

There are sailors in Rotherhithe, pubs, boats, and other assorted characters. Some of them, quite possibly, ne'er do wells. Hifferman's there of course. That's her sat next to the French artist Alphonse Legros on an alehouse balcony in Wapping. They're delightful and evocative images and you can, if you try hard enough, relate them to the slightly more gentrified Wapping, Battersea, and Rotherhithe of our times.

Battersea Reach (1862-63)

Wapping (1860-64)

Rotherhithe (1871)

Ratcliffe Highway (1861)

The Little Rotherhithe (1861)

While, random visit to Chile aside - the story is he intended to fight against Spain in a war for Chile's independence though that is heavily disputed, Whistler remained in London, his paintings of his woman in white started to travel around Europe and North America where they were widely admired. Not least by other artists. Many of whom had a crack at their own take on it.

Some were more successful than others. Albert Herter's Portrait of Bessie could almost be a direct tribute, the hard to pronounce Fernand Khnoff takes a more formal, almost starchy, approach, George Frederic Watts's Lady Dalrymple looks pensive and sad, and Gustav Klimt, of course, adds a bit of sparkle. Though remains relatively restrained by his own standards.

Albert Herter - Portrait of Bessie (Miss Elizabeth Newton) (1892)

Fernand Khnoff - Portrait of Madeleine Mabille (1888)

George Frederic Watts - Lady Dalrymple (1850-51)

Gustav Klimt - Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904)

Millais, despite comparing Whistler to Titian, goes against Whistler's ethos by implying a narrative in 1871's The Somnambulist (possibly, we're told, inspired by a romantic opera by Vincenzo Bellini), Rossetti went even further by including some slightly muddled moral message along with his interpretation, and Andree Karpeles provides a little bit of titillation for the viewer by allowing a cheeky little boob to pop out of his subject's white dress. In the case of Frederick Sands's Gentle Spring there's no need for that. The dress is completely see through. I've got a feeling he enjoyed painting that one.

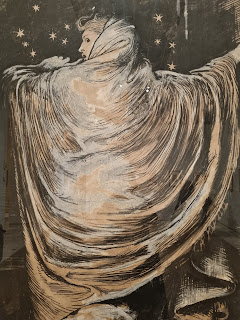

John Everett Millais - The Somnambulist (1871)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti - Ecce Ancilla Domine! (The Annunciation) (1849-50)

No comments:

Post a Comment