"If you put frightening things into a picture, they can't harm you. In fact, you end up becoming quite fond of them" - Paula Rego

Paula Rego's art, or at least most of it - when you first look at it, isn't frightening so much as it's disquieting, even a little disturbing in places. Seemingly innocent things are happening in many of her paintings but there always seems to be an undercurrent of tension. Either political, violent, or, perhaps most effectively of all, sexual.

The Policeman's Daughter (1987)

In 1987's The Policeman's Daughter it's all three and, because of that, it is, to my mind, a perfect example of what Rego does best. The young girl in a white dress, denoting innocence or virginity?, cleans her father's, the policeman's, boot. Police, not least in Portugal which only fifteen years earlier had still been a dictatorship, are both political players and violence workers and the way the girl's arm is wedged firmly into the boot is both sexually charged and sexually ambivalent.

Is she enacting her own desires or is she pliant in men's, or the state's, desires? The inclusion of a curious black cat in the foreground offers no answers but opens the painting up for yet more interpretation. These paintings, and others made in the mid-late eighties, are, to most fans of Rego, her most iconic. Yet her story is deeper and more interesting than just one high watermark over thirty years ago.

In her career, it seems to me, she honed down familiar themes over decades. Early works were hectic and colourful, latterly her palette has been more sombre. She began demanding a revolution in the land and now, as an octogenarian, she focuses more directly on the revolution we all must undergo in our own minds if we are to make sense of life as a human being in strange strange times.

Interrogation (1950)

Rego was born in Lisbon in 1935 at a time when Portugal was under the Estadio Novo (New State) dictatorship, one that would last until 1974. Political freedom was suppressed, Christianity was enforced, colonies like Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were forcefully maintained, and the rights of women were dramatically limited under the reign of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. Girls were expected to grow up to become obedient, and unquestioning, wives. This didn't play well with Rego's anti-fascist parents who wanted their daughter to grow up in a liberal country.

As Anglophiles, they enrolled her in a finishing school in Kent at the age of sixteen. One year later, she moved to the Slade School of Fine Art in Bloomsbury, London and there she met, and later married, fellow painter Victor Willing. After graduating she lived between Britain and Portugal, not settling in London permanently until 1972.

Early paintings, and 1950's Interrogation predates her ever attending art school, take inspiration from Rego's formative experiences in Portugal as a girl. They address the abuse of state power and they do it from a female perspective. Initially the work she made was intentionally grotesque as if to parody the brutality of the Salazar regime.

Interrogation looks at imprisonment and torture and aims to show not just the physical damage done to those suffering these two indignities but also the psychological pain. The head in the hand, the closed body, and the faceless prison guards all speak of despair and hopelessness but even at an early age Rego was aware that suffering could come from inside as well as outside.

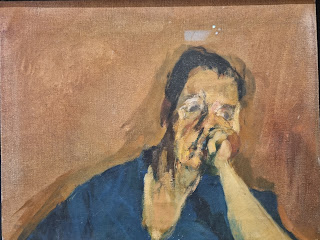

The portrait of her much loved father, Jose Figueiroa, shows him in the depths of the depression he was known to suffer. At his lowest ebb he would barely eat or speak and, instead, sit listening to the radio, to the BBC overseas service as they were the only ones reporting on what was really happening in Portugal at the time.

Portrait of Jose Figueiroa Rego (1954/5)

Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960)

How badly the political situation affected his mood can never be known but it seems highly unlikely that it was of negligible effect. The title of one work, 'When we had a house in the country we'd throw marvellous parties and then we'd go out and shoot black people', tells us how racist and murderous the fascists ruling Portugal were.

Rego's response was not always subtle. In Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, the dictator can be seen chucking his guts up next to a crudely drawn woman with exaggerated pubes. It's suggested that Rego felt that female sexual liberation was one of the best ways of dealing with the vomitous nature of the state. When it was displayed in Lisbon in 1972, Salazar's name was omitted from the title - even though he'd been dead two years.

Victor Musgrave, a supporter of Rego's early work, and his Gallery One in London refused to even display it. Other works meditated on eroticism in ways that were less capital P political. 1960's Turkish Bath is a mixture of painting and collage that caricatures the sexualisation of female bodies and, specifically, Oriental female bodies. Next to an advert for a late 1800s French medication said to enhance women's breasts there are scenes that represent, and poke fun at, the fetishised Orientalist paintings of Eugene Delacroix and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and it was made nearly two decades before Edward Said released his famous book on the same subject.

Turkish Bath (1960)

Always at Your Excellency's Service (1961)

Other works took inspiration from French 'art brut' Jean Dubuffet and she found humour the easiest, or at least safest, way to ridicule and attack the Portuguese dictatorship. Throughout the sixties and seventies much of Rego's work consisted of brightly coloured, busy, and humorous, if often hard to decipher, collages that bear witness to institutionalised injustice and express Rego's anger and anxiety about the state of Portugal as well as the wider world.

There's a surrealist tinge to these works as well as a folk art sensibility (Rego claimed she was as influenced by children's songs and events on the street as she was by her artist forebears) and, I learned at the Tate, they also reflect her experience of Jungian therapy. Something Rego had personally undergone herself, claiming it had awoken her desire to investigate human behaviour, and motivations for that behaviour, more deeply.

So we see northern Portuguese men in straw costumes dancing barefoot in the snow outside a fire station in Alijo - to celebrate their culture rather than the one being forced on to them, we see a martyr (based on Rego's long suffering father who died the year the painting was made) surrounded by ominous and incomprehensible forces, and we see the might of the military that oversees all of this.

The Firemen of Alijo (1966)

Manifesto (For a Lost Cause) (1965)

Military Manoeuvres (1975)

Self-Portrait in Red (c.1966)

But none of it we see clearly. Even a self-portrait, in Red, of the artist herself is partial, obscured, and abstracted. It's not that Rego didn't like making self-portraits (although perhaps she didn't, there's not many of them about) so much as this was her early style. Figurative, abstract, and surreal could all combine to create one image. It's as if she's telling a story in one image and, as such, there's times when it's a bit too much to take in.

To underline Rego's fondness of storytelling she developed a cast of animal characters whom she would use to illustrate her thoughts on the darker behavioural aspects of the human animal. 'Naughty' Red Monkey beats his wife and offers a poisoned dove to the more innocent, and gullible, Bear. Who, it seems, has walked straight in from an old Cresta advert ("it's frothy man" - one for the older readers) and would probably prefer a Fox's glacier mint anyway.

Red Monkey Beats His Wife (1981)

Red Monkey Offers Bear a Poisoned Dove (1981)

Untitled (1986)

Girl Lifting Her Skirt to a Dog (1986)

The Vivian Girls as Windmills (1984)

Truth be told, I think all explanations are equally valid and, possibly, intended. Rego capitalised on the ambiguity and after what feels like a fairly barren period in the seventies, no doubt sidetracked by that tricky business of raising three children, she began to hit her stride as a mature artist and as the artist we now celebrate.

This was done with a selection of paintings, included the aforesaid Policeman's Daughter, that have become the most iconic works she has thus far made. Large canvasses demand a large room and the Tate curators have been generous in giving one over to these works. In an exhibition that was never weak, this was, for me, the finest room in the entire show.

They were made up to and around Willing's death in 1988 and, unsurprisingly considering that event, they are deeply personal yet they are, as ever - perhaps more than ever, open to interpretation by the viewer. Multiple interpretations can and, I think, should be given. The position of the goose in The Soldier's Daughter, the girl about to murder - or pretend to murder at least, the family dog, another young girl kneeling deep into her father's crotch as she helps her mother undress him, and the innocence of sleep.

The Soldier's Daughter (1987)

The Little Murderess (1987)

Sleeping (1986)

The Family (1988)

The Dance (1988)

What dreams must they have? These works look at a woman's lot. Domestic duty, chores, constant sexual assessment by older men, and in 1988's The Dance (possibly Rego's most famous work) the process of ageing and how that is different, and made more difficult by both society and nature, for women than it is for men. They look curiously and passionately at a woman's life from childhood years to dotage and they show that these lives, though they may sometimes be mundane, are also full of magic and mystery.

As Rego's paintings are too. One of the things I like about them is that they make me complicit in my interpretation of them. For years, I would consider The Family and wonder if it was just me, pervy old me, that thought there was something a bit wrong about the level of intimacy between the characters that dominate the painting. The shadows, initially so reminiscent of Edward Hopper, loom out at peculiar angles to give the paintings a metaphysical characteristic found in the unsettling, but magnetic, works of Giorgio di Chirico.

I loved seeing these paintings and it was a pleasure to do so with my friend Sanda who, if anything, is an even bigger fan than me. I also enjoyed reading the legend of the pelican (seen in 1986's Sleeping) that pierced its own heart to feed its young with blood. All mothers have to sacrifice their selves in a degree to look after their children but that's a suitably grisly and fantastical demonstration.

Which makes it something Rego would, of course, be drawn to. If there was a fear that, following this large room, the exhibition would in some way drop off, it proved, thankfully, to be unfounded. The nineties found her delving back into the world of nursery rhymes and stories like Peter Pan, Pinocchio, and Snow White. Not so much the Disney versions of them but the disturbing Ladybird book versions.

The Barn (1994)

Island of the Lights from Pinocchio (1996)

Wooden boys, children that can't grow up, and beautiful women who fall into a deep sleep, effectively a coma, after taking a bite from a poisoned apple. These are children's stories? In the story of Pinocchio, naughty children are taken to a magic island to be punished by being transformed into donkeys and then sold into forced labour to either work in salt mines or perform in the circus.

Rego paints some Bosch like hellish vision of this in Island of the Lights from Pinocchio. Though, to me, the prone young lady with her dress hitched to flash her black knickers in a cowshed, while seemingly being whipped by two youngsters, is the more disturbing work. It is, an information board informs us, inspired by the gothic short story Haunted by the American writer Joyce Carol Oates.

When she wasn't looking to authors like Oates and Thomas Hardy, as well as nursery rhymes, Rego was producing paintings inspired by historical European painters like Diego Velazquez, William Hogarth, and Carlo Crivelli. With the notable difference that her works have been repopulated by females. Both to address a long standing imbalance and to give visual representation to the lived lives of women.

The First Mass in Brazil has a painting in the background (a painting within a painting) and it is Rego's version of an 1860 work, with the same title, by the Brazilian artist Victor Meirelles. In Meirelles' work the arrival of the first Portuguese men in Brazil (in 1500) is treated as a harmonious encounter. Rego imagines the encounter to be far more one sided and focuses on the experience of Brazilian women who were either sidelined or exoticised by the colonial Europeans.

The First Mass in Brazil (1993)

Time - Past and Present (1990)

Target (1995)

Sleeper (1994)

Soon enough, Rego moved away from addressing historical, and gendered, abuses of power and looked at how little we'd moved on. In 1994 she embarked on a series of large pastel paintings of single female figures. Her intention, which I believed she succeeded in, was for her sitters not to 'perform' for the male gaze. They may be in pain, they may be angry, or they may be sexually aroused but they are always all these things defiantly on their own terms.

Or at least through the prismatic eye of Paula Rego. Using, often, her main model of recent decades, Lila Nunes, as a sitter (or even 'muse' if you must), these paintings can suggest vulnerability (Sleeper) or even submission (Target) but they do so not from the normal angles that we, the male half of society, normally look at them. It seems an unlikely a male artist would paint Lila from behind in Target.

Not in the way it's been done, anyway. The Dog Woman series is even fiercer and more aggressive. There's something very primal about the poses struck and captured. It's hard to be certain if these women are in pain or consumed by anger or lust. The ambiguity, I imagine, is the point.

Bad Dog (1994)

Dog Woman (1994)

The Cell (1997)

Untitled No.4 (1998/9)

Untitled No.1 (1998)

The paintings journeyed further into gendered injustices and a series of untitled works from the late nineties looked at women who had undergone illegal abortions (a referendum to legalise abortion in Portugal was narrowly defeated in 1998 but one nearly ten years later finally changed the law). Rego fully intended for her paintings to sway voters towards voting for a change in the law and they are, certainly, powerful.

The quietly defiant, yet somehow still defeated, face that looks out from Untitled No.1 is open to multiple interpretations but, perhaps, 1997's The Cell was the most contentious. A baby, or the body of a baby, lies beneath the bed and it is possible to imagine this being sezied upon as eagerly by pro-life campaigners as it could be by those in favour of women making their own choices about their own bodies.

It's a curious work as regards to campaigning but extremely poignant as an artwork. With Nunes again as a sitter, Rego, in 2004, created a series called Possession in which she looked back to the 19th century and to the indignities the medical establishment, or society in general, dished out to women then. The term 'hysteria' was a catch all term of the time that covered everything from the presumed mentally weak state of women to 'demonic possession'.

Possession (2004)

Possession (2004)

Rego's contention was that the images of women who had been diagnosed with hysteria were very similar to those seen in Roman Catholic religious paintings. In this series she looked to further blur those lines and it's possibly instructive to learn that, at the time of their making, Rego was herself suffering from depression and undergoing therapy.

Something that surely bled into the work. Not least in the inclusion, in all the paintings, of a psychoanalyst's couch. While Rego took this journey inside herself she kept an eye on the outside world, its horrors, its injustices, and, also, its beauty and strangeness.

It's hard to know exactly what to make of 2005's Scarecrow and the Pig except that it riffs on many of Rego's trademark images:- sleeping women, animals as characters representing humans, and uncanny distortions of scale. A work like War, from two years earlier, is a bit easier to process. At least as a concept. As a comment on reality, in this case the bombing of civilians in Basra, it's hard to get your head round how man can continue to exact such cruelty on fellow man.

Scarecrow and the Pig (2005)

War (2003)

The Cake Woman (2004)

Circumcision (2009)

Human Cargo (2007/8)

Rego had been upset and horrified by an image of a mother carrying a baby through the aftermath of the explosion, while a girl screamed nearby, and as if unable to comprehend the tragedy on a human scale she converted the image into animal form. A bunny rabbit, as if from some horrifically weird children's story, carries her baby through the carnage while a children's toy lies abandoned.

What's happened to its former owner is left to our grisly imagination. It shows that even as Rego was dealing with her own personal demons she still felt, and expressed, the pain of those around her. Especially those most marginalised in society. Be it those undergoing intrusive and unnecessary medical procedures, those forced into slavery and bondage, those made victims of a war not of their own volition, or those simply seeking to escape a hellish existence to a better place.

Often to find out that they're not wanted there either. Now in her eighties, Rego is fighting, with her art, as strongly as she ever has for a better world. A world that treats the people, all the people, that live in it better, a world of respect and decency, and a world where women have agency over their own bodies and their own lives. A world, too, full of really rather wonderful art.

Thanks to Sanda for the company (and the coffee, cake, and chat beforehand of course) and thanks to the Tate for putting on this fantastic exhibition. Thanks, most of all, for Paula Rego both for being a courageous and inspiring artist and for standing against injustice where and when she finds it.

Escape (2009)

No comments:

Post a Comment