"My relationship to time is that of perhaps anyone who's never felt particularly fixed anywhere" - Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

"I write about the things I can't paint and paint the things I can't write about" - Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

No Such Luxury (2012)

I first encountered the work of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Serpentine Gallery about six years ago and, then again, back in July 2016 when she was featured in a show, Making and Unmaking, curated by the Nigerian fashion designer Doru Olowu at the Camden Arts Centre alongside artists as disparate as Dorothea Tanning, Alighiero Boetti, Claude Cahun, and Yinka Shonibare.

That was the first time I wrote, briefly, about her. Describing myself as 'entranced' by her work. But it was when I discovered her work in museums in both Seattle and San Francisco during an American holiday later that year that I realised she was far from being my own little secret, my own personal discovery.

In 2018 I attended All Too Human:Bacon, Freud, and a Century of Painting Life at Tate Britain and she held her own not just with Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud but with Frank Auerbach, David Bomberg, Paula Rego, Walter Sickert, and Stanley Spencer too so I was delighted that my first post-lockdown proper paying exhibition at a major gallery was Yiadom-Boakye's Fly In League With The Night at Tate Britain.

Black Allegiance To The Cunning (2018)

Any Number Of Preoccupations (2010)

It didn't disappoint. Even if, because of Yiadom-Boakye's relatively young age (still in her forties) and the lack of discernible narrative in her work over the years, it felt far more loose than a typical Tate retrospective. You don't look at her early work, her middle work, and then her later work and see how she changed and developed as an artist. You just get eight or so rooms each containing a selection of her rather wonderful paintings.

I say "lack of discernible narrative" because any narrative the viewer brings to the work is their own. The art of Yiadom-Boakye, it seems to me, demands that of us. In 2012's captivating No Such Luxury, a lady with brown hair and a brown top on looks back at us over a cup of tea. Her expression neither intense nor vacant. She is lost in a moment and we have no idea what that moment can possibly be.

A penny for her thoughts? Animals, too, feature alongside Yiadom-Boakye's imaginary sitters. You'll see foxes, dogs, and birds in this account alone. Animals are friends that never judge us and Yiadom-Boakye chooses not to judge her sitters either. They just exist - if only in hers and our minds. Sometimes alone. Sometimes in pairs. Sometimes in groups. Sometimes sat upright but often in relaxed poses. The double portrait Pale For The Rapture features two sitters who could either be tired, resigned, or simply kicking back.

Pale For The Rapture (2016)

Daydreaming Of Devils (2016)

To Improvise A Moutain (2018)

Some subjects assert their personality, the camply glamorous hero of Daydreaming Of Devils stands proud in front of an abstract background as if to dare us to pass comment. To Improvise A Mountain, one of the works that to my mind is most influenced by Rego, tells a less certain story. The lady on the floor is paying full attention to the person stood in front of her but is that attention earned or has it been demanded?

Yiadom-Boakye, you will have noticed, makes portraits of black people. There are no white faces on show at all in this exhibition and, of course, there is nothing wrong with that. She is not obliged to make portraits of anyone except those she chooses to. But I did notice it. Revisiting my account of a visit to a Lucian Freud exhibition at the Royal Academy last year, I note that the lack of black or Asian faces was not something I felt compelled to remark upon.

For Yiadom-Boakye there is a simple explanation:- "it isn't so much about placing black people in the canon as it is about saying we've always been here, we've always existed, self-sufficient, outside of nightmares and imaginations, pre and post "discovery" and in no way defined or limited by who sees us".

Six Birds In The Bush (2015)

11pm Tuesday (2010)

6pm Madeira (2011)

Her images are of people who are not real but are informed by real experiences. She omits almost anything that may place an image in a specific era or locale. Backgrounds are often fuzzy and unclear, abstracted, clothes are of classic or at least basic design, and shoes are mostly avoided.

Animals and musical instruments change much less with time so they are more often permitted to make the journey from imagination to canvas. When Yiadom-Boakye, the daughter of NHS nurses who emigrated to Britain from Ghana, attended Central St Martins College of Art and Design in London, the city of her birth, she didn't enjoy it. So she moved to Falmouth College of Art and there, in more remote Cornwall, she felt liberated and freer to express herself in a way that was true to her heart.

Which was to invent people that, to my mind, could, in their uncertain expressions, represent any one of us. Their thoughts and conversations are closed to us, as surely as the things they may be looking at - either directly or, in one case, through binoculars, but it is our human nature to try and interpret them. A lesser artist would nudge us in an obvious direction but Yiadom-Boakye leaves room for multiple readings.

Accompanied To The Kindness (2012)

The High-Mind And Disrepute (2020)

The paintings are, on the surface, deceptively simple - yet the passion and thought that underpins them are deep. Yiadom-Boakye aims to express universal feelings, to show both the surface and, in the eyes or the expression, what is beneath that surface. In Accompanied To The Kindess, the parrot's owner looks sad but defiant, The High-Mind and Disrepute, which reminds a little of Chris Ofili, depicts two friends enjoying music together, one of the finest bonding experiences two people can share.

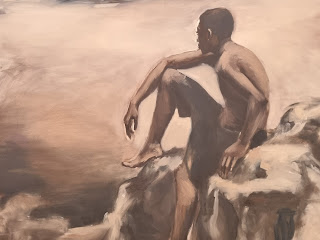

These are, of course, my interpretations. I can't attend a show of art that asks for interpretation and not at least interpret some of it. The Counter has a sense of the sublime, of awe, it could come from a rich tradition harking back to JMW Turner and Caspar David Friedrich while also reminding me of the paintings of Yiadom-Boakye's American contemporary Kehinde Wiley.

Amaranthine (2018)

The Counter (2010)

Hard Wet Epic (2010)

Hard Wet Epic has a classicist feel, its cast could be walking across a beach but they could, equally, be walking on the surface of Mars (even though they're clearly not dressed for it). A Bounty Left Unpaid looks like a still from a gritty movie, something by Cassavetes, and the russet coloured geometric blurs in the background of that painting could stand for an industrial part of a city or they could, just as easily, be a figment of our protagonist's imagination, a reflection of his mental state.

A Bounty Left Unpaid (2011)

No Need Of Speech (2018)

Few Reasons Left To Like You (2020)

The Woman That Watches (2015)

Geranium Love Sonnet (2010)

In Geranium Love Sonnet, a confident red haired lady in jeans and a pink vest top tilts her head to one side and looks out to us from between a table and a red wall. She could be having a friendly chat, she could be about to give someone a dressing down, or she could, for all we can tell, be waiting for someone to serve her a drink.

Songs In The Head shows two gentlemen chinking champagne flutes. Is it a business meeting, a wedding, or even a funeral? Similar questions could be asked of the group portrait Diplomacy I in which a group of men, women, and children stand suited and booted in an ill-defined landscape. Confusion is only added by the inclusion of someone in very different attire whose back is turned to the viewer.

Songs In The Head (2012)

Diplomacy I (2009)

All Manner Of Comforts (2016)

Complication (2013)

It's hard to work out what the 'complication' in Complication is (unless it's the fact that one guy's gone and wore white pants on black pants day) and it's even more difficult to read a more recent, and seemingly darker in intent, work from last year called The Stygian Styx in which a young man with his hounds meets our gaze via a cracked and distorted image that borders on the uncanny.

It's a painting that shows that Lynette Yiadom-Boakye's work can, and surely will, branch off in new directions as she continues her career but it is also one that asserts that Yiadom-Boakye is already, now, fully developed as a major British artist. As such this exhibition was timely and compelling and, for me, a great return to visiting London's major art galleries after way too long an absence.

The Stygian Silk (2020)

No comments:

Post a Comment