When American feminist and social activist bell hooks (lower case, her personal preference) wrote or said these short but insightful words I like to think that she didn't just mean love for others, romantic love, or even familial love. But that she was also referring to the love we must give ourselves. At how we must work at loving ourselves.

It's so easy to always put ourselves down. It can be a pro-active choice, get in there with the negs before somebody else does, or it can come from a sense of personal disappointment that we have not become the perfect person, the perfect lover, the perfect parent, the perfect child, or the perfect friend we would have hoped to have grown into.

Last year's Rock My Soul exhibition at the Victoria Miro Gallery on Wharf Road in London saw the British artist and film maker Isaac Julien borrows its title from hooks' 2003 book, Rock my soul:black people and self-esteem, in which the author investigates how self-esteem within black communities, and within individuals of colour, can play an important role in both cultural and political empowerment.

Lynette Yiadom Boakye - A Clay Herald (2019)

hooks writes "without self-esteem everyone loses his or her sense of meaning, purpose, and power". So what's obviously required here is a white, heterosexual, middle aged, man's perspective on the exhibition. We all know we don't get nearly enough of that these days!

Fear not though. I'm not one of those who like to claim that white men are the most oppressed group on the planet just because the political world, the art world, the worlds of music and television, and the world in general is finally waking up to the fact that having stories and narratives presented from different backgrounds might give a fairer representation of what people think and like. I totally get that the wider the net is spread the better it is for all of us. It's not a zero sum game, ffs, you knuckleheads.

I also feel safe that I'm not treading on any one's toes by writing this because it's a blog, anyone can write one, and I'm not getting paid for it. I'm doing it for the love of it, a distorted sense of duty to myself, and in the vain hope that someone, somewhere, might read it, get some pleasure out of it and, maybe one day, just maybe, give me some money to write. I need to eat!

Fear not though. I'm not one of those who like to claim that white men are the most oppressed group on the planet just because the political world, the art world, the worlds of music and television, and the world in general is finally waking up to the fact that having stories and narratives presented from different backgrounds might give a fairer representation of what people think and like. I totally get that the wider the net is spread the better it is for all of us. It's not a zero sum game, ffs, you knuckleheads.

I also feel safe that I'm not treading on any one's toes by writing this because it's a blog, anyone can write one, and I'm not getting paid for it. I'm doing it for the love of it, a distorted sense of duty to myself, and in the vain hope that someone, somewhere, might read it, get some pleasure out of it and, maybe one day, just maybe, give me some money to write. I need to eat!

Frida Orupabo - Untitled (2019)

Karon Davis - Hair Peace (2019)

But there I go again. Banging on about myself. As if this is all about me. Let's get back to the art. Some of it is great. None of it is terrible. I've been a fan of Lynette Yiadom Boakye for a few years now so I was very pleased to see one of her works in the show. Although not as excited as when I came across a painting by the London born painter in galleries in Seattle and San Francisco four years ago. It's good to see a fellow Londoner make it in America.

Yiadom Boakye's paintings, like 2019's A Clay Herald, aren't flash. They aren't offering up a revolutionary new way of painting but they're imbued with a quiet dignity, a pensive pride, that draws the eye to them and holds one's attention as we imagine their back stories. Her sitters seem to be caught in a private moment and, as such, they disarm our gaze in a gentle, but powerful, way.

Julien's curation aims to look at how artists respond, either via abstraction or figuration, to established art movements and how they find themselves a place in the canon, and the artists gathered together at the Victoria Miro come from a wide range of backgrounds, countries (I spotted the UK, the USA, Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, and Norway but I could easily have missed something), and age groups.

Whilst Frida Orupabo's untitled meditation on fatherhood and the pride it can instil in a person and Karon Davis' Hair Peace were distracting and touching, I was drawn more to the works of Howardena Pindell, Sonia Boyce, and Tschabalala Self initially. Pindell (who's cropped up in previous reviews I've written of Stephen Friedman Gallery's Painting on the Edge of Elasticity, Victoria Miro Mayfair's Surface Work collection of female abstraction, and even Tate Modern's 2017 blockbuster Soul of a Nation:Art in the Age of Black Power) is slowly winning me over. Her Slavery Memorial:Lash may be abstracted and hard to read but its intent, quite clearly - the title alone is enough, is overtly political and the points she's trying to make seem, to me, about how the historical crime of slavery has left scars that may still take many generations to heal.

Howardena Pindell - Slavery Memorial:Lash (1998-1999)

Sonia Boyce - Talking Presence (1987)

Tschabalala Self - Princess (2017)

Longer still, if racism continues to not just fester but is actively encouraged by the new breed of populist world leaders for who, sometimes, even a dog whistle isn't enough. London's Sonia Boyce takes her home town as her inspiration, America's Tschabala Self the black female body. Both are full of colour and movement and both seem vitally alive. Big Ben, St.Paul's Cathedral, Tower Bridge, and a red London bus create a body from the city and Self's Princess seems to create a city from a body.

I love her use of purples, reds, and dark blues in a portrait that seems just as inspired by Picasso as it does the Harlem Renaissance. Njideka Akunyili Crosby's Remain, Thriving is even better. For me, it's the best work in the show but I'd find it hard to articulate why. The Nigerian artist has used collage to create a peaceful looking family scene, check out the nipper in the pistachio green romper suit, that manages to suggest both domestic bliss and a sense of remove that comes from displacement.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby - Remain, Thriving (2018)

Wangechi Mutu - She Walks (2019)

Zanele Muholi - MaID III, Philadelphia, 2018 (2018)

The likes of Wangechi Mutu, Zanele Muholi, and Betye Saar go in harder. The people in these works don't look so comfortable. Anything but. Wangechi's She Walks seems to suggest recovery from setbacks and oppression while Muholi's pair of Philadelphian portraits featuring sitters with their hair restrained by unnecessarily strong clips and what looks like a mesh shopping bag suggest subjects still oppressed. Or, at the very least, being made to feel a great deal of discomfort at, being both female and black, as something other. Something exotic.

They're not real people but I could barely meet their eyes! Betye Saar, now ninety-three years old, was the only artist to be given an entire room to her self in the aforementioned Soul of a Nation show at Tate Modern and despite all the wonderful art included in that show that didn't seem unfair. Her co-opting of novelty items to include racist motifs from (mostly, hopefully) the past has a soft power that can unnerve and move the viewer.

It's just my take but what I think she's doing here is showing us that historical racism, and the racism we still have now, is not to its practitioners some kind of outlier. It's not one odd thing they believe but it's at the very heart of their thinking. Many of us will know a racist relation who, on occasions, it's not possible to avoid being in a room with. We'll have tried most things.

We'll have tried confronting them. We'll have tried rationally explaining to them the ludicrousness of their position. Eventually we'll try to ignore either them or the subject of race entirely (which is only possible if you're the same race as them of course) but, you'll have probably noticed, that's not enough for racists. They choose to highlights their prejudices even when you're trying to steer the conversation on to safer ground. How's your health? I can't get an appointment at the doctors because all the foreign scroungers are prioritised. How was the traffic? Terrible, all the roads are clogged up because there are too many immigrants here on benefits.

We'll have tried confronting them. We'll have tried rationally explaining to them the ludicrousness of their position. Eventually we'll try to ignore either them or the subject of race entirely (which is only possible if you're the same race as them of course) but, you'll have probably noticed, that's not enough for racists. They choose to highlights their prejudices even when you're trying to steer the conversation on to safer ground. How's your health? I can't get an appointment at the doctors because all the foreign scroungers are prioritised. How was the traffic? Terrible, all the roads are clogged up because there are too many immigrants here on benefits.

Betye Saar - We Was Mostly 'Bout Survival (Inning) (1997)

Zanele Muholi - Cebo II, Philadelphia, 2018 (2018)

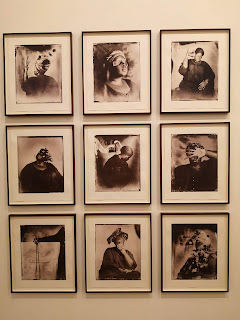

Khadija Saye - in this space we breathe series (2017-18)

Those last two examples are both things that have, more or less verbatim, been said to me by people in the last few years. More than once. These people wouldn't identify as racists but their words undoubtedly are. In showing that racist behaviour and racist words are as everyday as kitchen, or even, novelty items, Betye Saar shows us how these seemingly minor infractions slip under the radar and create a racist, xenophobic environment that those of us not victim to may even find easy to ignore.

Saar's work highlights the dangers of everyday racism using everyday items and if I felt Njideka Akunyili Crosby's work was the most aesthetically pleasing in Rock my Soul then Saar's was the most interesting. The most powerful, however, has to be the one I've left until last. Khadija Saye's "in this space we breathe series" from 2017-18.

The British-Gambian Saye was just twenty-four years old when she died, on 14 June 2017, along with 72 others, in the Grenfell Tower in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. She'd achieved some recognition as a talented artist and it seems highly likely she would have gone on to much better things.

We'll never know that for certain, though, because the system that allows immigrants, people of colour, and poor people to live in accommodation that would never be deemed safe for rich, white people to live in is still in place. With the election of an openly, and unashamedly, racist Prime Minister last December the system is not just still in place but has more power than it has done in my life time.

Khadija Saye described her work as a means to explore "the deep-rooted urge to find solace in a higher power". I suspect she meant in a religious way and though I'm not religious that's probably for the best because I think we all know we have a government now that is far more committed to pushing more people into poverty, and danger, than it is to lifting them out of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment