If you're the sort of person who perceives the adjective 'flowery' in the pejorative then the Royal Academy's new show Painting the Modern Garden:Monet to Matisse may not be the one for you. Entering the first room is like being part of Diana's cortege as pelargoniums, lilacs, and other assorted Morrissey back pocket accessories immediately assault your vision.

The RA are attempting to tell the story of art, or even life itself, from the 1860s to the 1920s through the prism of botanical paintings and they've assembled a cast of some of the biggest names of the era's art world to do it. Starting with the Impressionists seems reasonable enough. Often the view taken is that a retreat into the wilderness of the garden was a refuge from the industrialisation of the time. Though it could also be said that some artists' new found wealth enabled them to live in bigger properties with larger gardens and enjoy more free time in them.

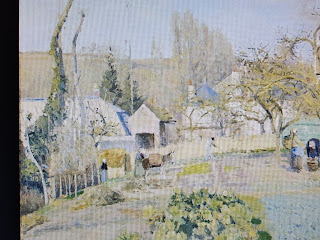

There are works in the first rooms from Cezanne, Manet, Bazille (who leaves our story early having died in 1870 in the Franco-Prussian war). My favourite is a piece by Camille Pissarro, a man who sported an even longer beard than Monet, called Kitchen Gardens at L'Hermitage from 1874. It's very yellow and that shines out amongst the greenery surrounding it.

Gustave Caillebotte was an artist I'd previously known very little about but as we move deeper into the circle it's his paintings that make the biggest impact. His Nasturtiums (1892) appears almost abstract from the right distance.

Caillebotte also stepped away from pure flower painting to depict workaday vegetable gardens, rendering walls as beautiful as the greenery. You can also witness Berthe Morisot's looser brush strokes pointing the way for later developments.

By the 1880s gardens, and their depictions, were getting more tropical. Monet's particularly. Not least because they were painted in the Italian seaside village of Bordighera. This paves the way, the curators hint, for garden painting to leave France and go international. John Singer Sargent's rather stuffy works pale next to those of Joaquin Sorolla (who had a very cushy job travelling around the gardens of his native Spain). You may wish to avoid his portrait of Tiffany, the jeweller, in his whites though. Unless you possess either a pair of shades or a strong stomach. It's a bit icky.

Childe Hassam shows up from across the Atlantic, painting poppies in Maine. Max Liebermann's ur-Auerbach oily splodges compete with his Nordic looking trees in his Wannsee gardens works. They're pretty good if a little surprising in the context they're presented in. Johan Krouthen's family portrait from Linkoping brings both Sweden and a sense of narrative into the genre. There's two sets of chrysanthemums and Dennis Miller Bunker's seem very different to Tissot's. It could be down to the latter employing the inclusion of a very Victorian lady and the former showing an empty path. Something that crops up often in this exhibition.

Scattered amongst the paintings there are books about dahlias, pictures of the stars painting plein air, seats for the expected older patrons to relax, and a room on how to make your own garden. This contains catalogues of aquatic plants, nursery delivery slips, photos of Monet in his big hat from a 1933 issue of Country Life, and, best of all, some exquisitely beautiful Hiroshige and Hokusai woodblocks. Japan, at the time of the show, having only recently opened up trade with the West. It's easier to see how these influenced garden design than the art itself . Not least in Monet's Giverny (his Japanese footbridge from 1899 below) which has an entire room devoted to it.

His water lilies too of course. Pink ones. Green ones. Dreamy ones. Serene ones. Years and years worth. As we know the effect of light on the given subject was one of Monet's great gifts to the art world. After all that his peonies look almost brutal. Which set you up for the Gardens of Silence.

Joaquin Mir Y Trinxet's The Artist's Garden from 1922 hints at an aura of mystery and is contrasted well with Santiago Rusinol's Spanish palaces. Rusinol's use of colour lights up the room which has been, oddly, if effectively, darkened. It's a score draw between Spain and Catalonia here.

Not all the curator's party pieces come off so well. The avant-garden pun was one they clearly couldn't resist. The room's good though. Dufy's tropical tones play off against Nolde's fauvist smudges. August Mache's menacing garden path echoes those of Bunker earlier. Matisse brings a sense of naivety to the party, Van Gogh turbo-charges Impressionism, and Munch's childlike, yet frantic, expressionism is a delight. There's even a Klimt. Klee, as ever, has something of the East about him. Klee loved to paint plants and made about 10,000 works in the discipline. Roughly 10% of his entire output.

The Nabis, Bonnard, and Denis seem like they've stepped back in revulsion from the flowering of the avant-garde(n?) and, in retrospect, appear too safe and cosy. Vuillard is an honourable exception but at the end you're thrown straight back into the revolution happening in art. Which is where this show is at its best. When it follows a narrative it works well. When it deviates it's trickier. Luckily the script is stuck to more often than not.

The final rooms are devoted to Monet and Monet alone. Many water lilies and some rather dark canvases. Compare his Japanese Bridge of 1923, below, to the one from only 25 years before and you'll wonder if contemporary critics thought he'd gone senile.

Perhaps he had. He was certainly very old and had become deeply affected with World War I raging across Europe. The memorials for which would find flowers reverting back to one of their more traditional uses.

Thanks to Kathy Smith for enabling this cultural outing.

No comments:

Post a Comment