Pete Keetman - Steel Pipes, Maximilian Smelter (1958)

Tate Modern's excellent Shape of Light:100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art tells the story of how two seemingly opposing mediums met in the middle, inspired each other, and helped move the story of art in new and unexpected directions. I'd often considered that part of the reason abstraction became so dominant in modern art was the rise of photography and how the camera was able to capture reality with more veracity than the paintbrush.

Shape of Light rips that notion in half, screws it into a crude ball, and lobs it into the nearest waste paper basket. For once the premise of the exhibition, that it "invites the viewers to challenge their conventional perspectives" is both met and bettered. In the words of French snapper Pierre Dubreuil "why should the inspiration that comes from an artist's manipulation of the hairs of a brush be any different from that of the artist who bends at will rays of light?".

We learn how sometimes photographers would follow painters and sometimes painters would follow photographers. Often they'd simply inspire each other, push each other forward in unexpected and exciting ways. What Piet Mondrian did with a paintbrush, German Lorca did with a camera.

Shape of Light rips that notion in half, screws it into a crude ball, and lobs it into the nearest waste paper basket. For once the premise of the exhibition, that it "invites the viewers to challenge their conventional perspectives" is both met and bettered. In the words of French snapper Pierre Dubreuil "why should the inspiration that comes from an artist's manipulation of the hairs of a brush be any different from that of the artist who bends at will rays of light?".

We learn how sometimes photographers would follow painters and sometimes painters would follow photographers. Often they'd simply inspire each other, push each other forward in unexpected and exciting ways. What Piet Mondrian did with a paintbrush, German Lorca did with a camera.

Piet Mondrian - Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue (1935)

German Lorca - Mondrian Window (1960)

Wyndham Lewis - Workshop (c.1914-5)

Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticists used hard angles, clashing colours, and daring diagonals to express the confusing geometry of modern life. Kandinsky employed triangles, circles, and grids to a similar, even more brilliant, affect. Photographers like Alvin Langdon Coburn and Marta Hoepffner were inspired by these canvases, as well as some of the modernist composers who were emerging, and using stencils and photographic paper they created pieces that appear to be more homage than individual art in its own right. This exhibition tells how that would change.

Wassily Kandinsky - Swinging (1925)

Marta Hoepffner - Homage to Kandinsky (1937)

Georges Braque - Mandora (1909-10)

About the same time Picasso and Braque were pioneering Cubism, American photographer, and lover of Georgia O'Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz was launching Camera Work, possibly the first journal that promoted photography as a fine art, as well as opening the 291 gallery in New York to provide a platform for these new fine artists. He'd juxtapose photography with sculptures by already established, and revered, artists like Constantin Brancusi as if to say there really is no difference. Photography can be art in its own right rather than something that pays homage to art. Paul Strand even went as far as to name his photographs 'abstractions'.

Paul Strand - Abstraction (1916)

Constantin Brancusi - Malastra (1911)

Brancusi's interest in photography, initially as a device to promote his work, was piqued after a meeting with Man Ray and when the US authorities, in 1927, decided that Brancusi's Bird in Space was not sufficiently artistic to be considered art, it didn't look enough like a real bird, and classified it, bizarrely, under 'Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies' the photographer Edward Steichen testified in a court case that saw that decision reversed and the US courts, legally at least, recognising that now artists were as free to 'portray abstract ideas' as they were to 'imitate natural objects'.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy claimed we had been "enormously enriched" by the advances in photography and film to the degree that we now "see the world with different eyes" and he was right. In Weimar Germany the Bauhaus school opened in 1919 and, along with similarly motivated movements in Russia, they had no hesitation in accepting that photography stood on an equal footing with both painting and architecture.

Moholy-Nagy was one of the Bauhaus' most influential teachers and together with his wife Lucia, who'd been the one to introduce him to photography, he set about demonstrating just how suitable the medium was for capturing the tropes of modern life:- skyscrapers, machinery, etc; New inventions needed new perspectives and through experimentation, extreme close ups, tilted horizons, and fragmentation Moholy-Nagy and others, for example the Bauhaus trained Iwao Yamawaki and Jaroslava Hatlakova, were able to provide those new perspectives.

Edward Steichen - Bird in Space (1926)

Jaroslava Hatlakova - Untitled (1936)

Iwao Yamawaki - Untitled (Textile Abstraction) (c.1930-3)

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy - K VII (1922)

Moholy-Nagy's own K VII, painted in Berlin in 1922, owes a debt to Mondrian but also to his own developments regarding line, shape, and form in photography. The K in the title represents the German word konstruktion, one you probably don't need me to translate for you. As if to acknowledge its debt to both these sources it's been hung near one of Moholy-Nagy's own, admittedly later, photos that renders the view from the Berlin Radio Tower as almost geometrically abstracted and a piece by Mondrian's compatriot and contemporary, and founder of De Stijl, Theo Van Doesburg. It's said, and repeated often by me, that Mondrian was so horrified when Van Doesburg included a diagonal line in his work they didn't speak for years. Artists!

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy - View from Berlin Radio Tower (1928-30)

Theo van Doesburg - Counter-Composition VI (1925)

Man Ray, also, was less interested in capturing reality than creating his own. Each room in the exhibition is prefaced with a quote and Man Ray's offering is "I think that, instead of producing a banal representation of a place, I'd rather take my handkerchief out of my pocket, twist it to my liking and photograph it".

Much like Moholy-Nagy the Philadelphian son of Russian Jewish immigrants, born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, Man Ray was starting with something quite normal, something you may see almost every day, and using his camera to make it seem strange, or otherly. In fact much of his work wasn't even made using a camera but by simply laying objects directly on to photosensitive paper.

Others, like the amateur Chinese photographer Luo Bonian, the Milanese scenographer Luigi Veronesi, and the Hawaiian born Japanese-American Kira Hiromu, used similar techniques utilising views of construction sites and the detritus of everyday to life to make images that both appease and wrongfoot the eye.

Hiromu's Circles plus Triangles uses both shape and shadow to evince a delightful, and somewhat melancholic, image. It's one of many really quite simple delights in this extensive show and it's worthy of a place next to the paintings of Polish Constructivist Karol Hiller and Strasbourg's Jean Arp.

Luo Bonian - Untitled (1930s)

Luigi Veronesi - Untitled (Spiral) (1938)

Kira Hiromu - Circles plus Triangles (c.1928)

Karol Hiller - Heliographic Composition XXIV (1938)

Jean Arp - Constellation According to the Laws of Chance (c.1930)

Man Ray - Rayograph - 1922-7

The Hungarian-French photographer and medalist Brassai (Gyula Halasz to his parents) was in accordance. He opined that "there is nothing more surreal than reality itself" before, warming to his theme, following with "if reality fails to fill us with wonder, it is because we have fallen into the habit of seeing it as ordinary".

Andre Breton's Surrealist Manifesto had been launched in 1924 and the Surrealists embraced photography as a tool for rejecting rational visions in favour of the celebration of dreams, the unconscious, and the downright weird. Brassai's 'Involuntary Sculptures' series, often captioned by Salvador Dali, contained images of toothpaste, soap flakes, and rolled up bus tickets presented as if they were monumental. Budapest born Andre Kertesz and the Hamburg born British photographer Bill Brandt used the human form, distorted or seen from an unusual angle, to create disconcerting images, almost as if viewed from a hall of mirrors. I'm not totally buying that their painted equivalent is Joan Miro but Miro's work is lovely so it's made the cut anyway.

Brassai - Involuntary Sculptures (1932)

Andre Kertesz - Distortion 88 (c.1933)

Joan Miro - Painting (1927)

Bill Brandt - East Sussex Coast (1960)

The word photography, I am reliably informed, comes from 'photos', the Greek for light, and 'graphe' meaning drawing, and the examples on show from William Klein (who'd studied under Fernand Leger) and Saarbrucken's Otto Steinert really illustrate this. The Surrealists believed that applying chance to the creation of art freed the artist from the constraints of rational thought and you can see how Klein, and more so Steinert, despite neither of them being strictly Surrealists, had taken these lessons on board.

Steinert's Luminogram 2 from 1952 looks as if it's been taken from a moving car using a slow shutter speed yet it's oddly beautiful and somewhat reminiscent of the large Abstract Expressionist paintings of both Clyfford Still and Jackson Pollock. Pollock, like Steinert, was not a Surrealist but in his technique of Action Painting he, more than any artist before him, found the most convincing way to move away from the dictatorship of the rational mind. The fact they're also a pleasure to look at is almost a bonus. Putting Steinert and Pollock together in the same room was one of the great successes of an exhibition that had very few outright disappointments.

William Klein - Untitled (Rotating Painted Panels), Milan - 1952

Otto Steinert - Luminogram 2 (1952)

Jackson Pollock - Number 23 (1948)

Steinert wasn't only an innovator and taker of impressive photographs. Keen, post-war, on reviving the innovative spirit of Bauhaus, he formed a group called fotoform and arranged a touring exhibition, Subjective Photography, that featured artists from around the world and was intended to show how broad and encompassing the world of photography could be.

That's an honour that could have been heaped upon Steinert, Pollock, Ishimoto, Yamomoto, or, indeed, any of Keetman's other works on show at Tate Modern. Makarius's view of Buenos Aires' Art Deco Kavanagh building obscured by both fog and overhead cables is masterful, de Barros's blurred chair a delight, and Keetman's Chiemsee at Breitbrunn evocatively sad. These works seem to be stretching out into the future of photography much like the stone path in Yasuhiro Ishimoto's untitled piece.

Geraldo de Barros - Untitled (Sao Paulo) Composition II (1949)

Sameer Makarius - Kavanagh Building under the Fog (1954)

Geraldo de Barros - Granada, Spain (1951)

Yasuhiro Ishimoto - Untitled (c.1950)

Iwase Sadayuki - Concrete Edge and Water (c.1940)

Kansuke Yamamoto - Title Unknown (1940)

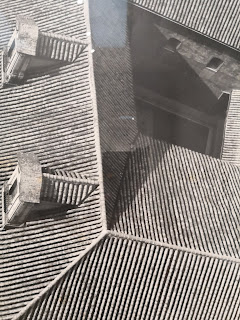

Pete Keetman - Window Frame (1937)

Pete Keetman - Chiemsee at Breitbrunn (1958)

The future it looked forward to was a messy, scrappy uncertain one full of peeling paint, peeling posters, scratched surfaces, and faded glamour. These 'found paintings' were, again, symbiotic with the Abstract Expressionists. You can see echoes of Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning in Brassai's 'Graffiti' series, there's no little similarity between Jacques Mahe de la Villegle's 1961 Jazzmen and the psychogeographical decollages of Italian Ultra-Lettrist Mimmo Rotella.

Mahe de la Villegle wanted to emphasize the actions of anonymous passers by who'd pick away, tear, and strip posters from walls in an action that he considered to be spontaneous, unconscious even, art. In some ways it was the next logical step from Jackson Pollock. Pollock felt the artist's hand no longer needed to touch a brush or even a canvas. Mahe de la Villegle felt the artist hardly needed to be involved in the creation of the work at all. Echoes of the Duchampian readymade, sure, but also, as with Pollock, delivering stunning, eye catching, results,

Brassai - Graffiti (c.1950s)

Brassai - Graffiti (c.1950s)

Jacques Mahe de la Villegle - Jazzmen (1961)

Aaron Siskind - New York (1930)

Aaron Siskind, often described as 'a painter's photographer', taught, in the early fifties, at Black Mountain College in North Carolina with Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg and had his work exhibited in New York alongside paintings by De Kooning and Franz Kline. He'd mount his work on blocky Masonite hardboard as if to underline that these were to be treated with the same reverence, the same awe, as the paintings of his contemporaries.

While some photographers were influenced and inspired by, or were influencing and inspiring, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Cubism, or even Dada others had thrown their lot in with the Op Art movement, which saw the likes of Bridget Riley, Victor Vasarely, and Franco Grignani use optical illusions in their work to create the impression of movement.

Photographers responded to the swelling and throbbing dots and lines of the painters by employing turntables, filters, and oscillographs to both produce striking images and, once more, to remove the curatorial hand of the artist themselves from the artwork.

Bridget Riley - Hesitate (1964)

Gottfried Jager - Pinhole Structures (1967)

Some of these pieces, for instance Gottfried Jager's Pinhole Structures, used mathematical formulae in their creation as if now freed from direct human interference they still sought order. Minimalist artists like Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, and Donald Judd would develop these techniques by reducing what our eyes see and process down to the bare essentials.

Minimalism claimed that 'art should have its own reality and not be an imitation of anything else'. It seems to me to be more of a development of the ideas of Abstract Expressionism than a completely new form but, like Abstract Expressionism before it, it certainly divided the critics as anyone who remembers, or has read about, the furore concering Andre's pile of bricks at the Tate will know.

Ellsworth Kelly's art is colourful and bold but his photography seems to come from another place. It'd be hard to make a case for it being Minimal with a capital M, too figurative, but it's certainly minimal in its subject matter and it's a delight for the eyes. He's managed to coax so much beauty, so many feelings, out of a simple Los Angeles sidewalk and a wall in Majorca that I'm reminded of William Blake's Auguries of Innocence, "to see a world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower" and TS Eliot's Wasteland "I shall show you fear in a handful of dust". Inanimate objects tell dark and complex stories that often belie their simplicity.

Ellsworth Kelly - Sidewalk, Los Angeles (1978)

Ellsworth Kelly - Wall, Majorca (1967)

It doesn't seem as if the Californian photographer Lewis Baltz was looking for infinity in small images though. Baltz claimed that "photography is the only deductive art, every other art that I can think of begins with the topic tabula rasa, or a blank sheet of A4 paper. Photography begins with a world that's perhaps over full and needs to sort out from that world what is meaningful".

It's hard to claim that an air conditioning unit and the serrated marks of what look like a former doorway are particularly meaningful but they're certainly photogenic in surprising ways. So too Andre's Steel-Zinc Plain which wasn't roped off, almost inviting visitors to leave their dirty footprints on it. Ed Ruscha's work can range from the sublime (his gas stations) to the terrible (big lazy words) and his photography sits squarely in the middle of that. It's not that its bad, it's quite curious, but his Parking Lots series doesn't seem to have anything to offer that Laszlo Moholy-Nagy hadn't already done nearly four decades earlier.

Lewis Baltz - San Jose (1972)

Carl Andre - Steel-Zinc Plain (1969)

Edward Ruscha - Parking Lots (1967-2013)

Edward Ruscha - Parking Lots (1967-2013)

Jay DeFeo - Untitled (1973)

Jay DeFeo cropped up in the recent Surface Work exhibition of female abstract art at the Victoria Miro Gallery and I commented then that they'd not used one of her best pieces. Shape of Light did a bit better, her 1973 Untitled piece at least makes one think, but, again, she's made better stuff. Perhaps she's due a retrospective.

The exhibition concludes with photography's future as uncertain as ever. Divergent strands of the medium populate the last room as the battle, one that rages in all our heads, between control and order and chance, accidents, and, ultimately, freedom rage on. Digital cameras and mobile phones have democratised the process of picture making yet with such a wealth of it now available it is, in a world where any old tosser can be a content provider, an almost full time job sorting the wheat from the chaff. Some of the artists in the last room, alas, are chaffier than they are wheaty.

The Canadian artist Stan Douglas uses JPEG files and mixing desks to make vertical bands of colour and pretty patterns and he, like many contemporary photographers, sees the process of making the photograph as much, maybe more, the work of art than the results of that process. That's a little indulgent, a bit wanky even.

Stan Douglas JNNJ (2016)

Stan Douglas - QAAQ (2016)

These were the same problems I had with the work of Thomas Ruff when I visited his retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery back in January and those problems with Ruff's work still linger. If you're making art just to please yourself then why show it in a gallery? I find when having a conversation with someone it's often best if you ask them some questions and listen to what they're saying. Art too, I believe, works better as a dialogue than it does a monologue. That's why, for me, Andreas Gursky is so much better, so much more important, than Thomas Ruff.

Thomas Ruff - phg.10 (2012)

Daisuke Yokota - Inversion (2015)

If Ruff and Douglas don't look like, and hopefully aren't, the future of photography then the works of Aphex Twin fan Daisuke Yokota and Swiss lover of colour Maya Rochat may well be. Both still in their thirties, they operate at different ends of the spectrum (Daisuke's work is as dark as a Joy Division album, Rochat's a park on a summer's day viewed through a kaleidoscope) but both seem to be pushing the medium gently forward.

Yokota claims no meaning in his work other than a desire to interact with his public while Rochat asserts that her wish is to activate an ever changing show, a constant parade of people, colours, feelings, and moments. Like Douglas and Ruff, Yokota and Rochat consider the process to be as important as the end results but unlike Douglas and Ruff they've made sure the end results both capture something of the process and are interesting to look at and to me that's key. Make something in a novel, experimental way for sure but make sure people might like to actually see. It doesn't have to be figurative and this show both knows that and shouts it from the rooftop loudly and proudly. I'd had preconceptions shattered and I'd had preconceptions enforced. It was that kind of experience. The proverbial mixed bag. But there was way more good stuff than bad. I came. I saw. I learnt. I went home and wrote more than 3,000 bloody words about it.

Maya Rochat - A Rock is a River (2018)

No comments:

Post a Comment