It wasn't easy to find the With Graphic Intent exhibition in the Courtauld Gallery. I'd been up and down several spiral staircases and I'd been round a fair bit of their permanent collection (checking out Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Degas, Rubens, Modigliani, Seurat, and Lucas Cranach the Elder) before I noticed a small sign pointing to a very small side room, about the size of a child's bedroom, where the exhibition was.

Oskar Kokoschka - The Girl Li And I (1907)

It was a bit of a mixed bag of a show too (but it was free with my Art card so I'm not complaining). The basic gist is that it's a show of paintings, and drawings, from German and Austrian artists of the early 20th century. When those artists began the supposedly 'radical' process of painting on paper rather than canvas. That doesn't seem enough to hang a show on in its own right. Or at least the curators seem to think so as they've tied it in with what seems to me an entirely different topic.

That of the cultural attitudes towards women shown by artists, and society itself, during that era. That's an interesting, and worthwhile, story to tell. But I'm not sure that the two stories really go that well together. I don't want to accuse the curators at the Courtauld of trying too hard to force a woke agenda but, er, that does seem to be what's happened here.

It might have worked better if they'd made the whole exhibition about that but to be fair to them, some of the artworks on display definitely seem to dwell on fragile masculinity and the perceived threats it was facing during this era. Or, it seems, any era from thereon in.

Oskar Kokoschka - The Sleeping Girl (1907)

Oskar Kokoschka's series of paintings convert what would appear to be a fairly innocent fairy tale into a meditation on sexual awakening. Kokoschka was twenty-one at the time and had, we discover, fallen in love for the first time. The Sleeping Girl is surrounded by bright red, and rapacious - we're told, fish and in The Girl Li And I we have a version of Adam and Eve who seem to be near but not in (possibly unable to get in) the Garden of Eden where snakes copulate and birds kiss.

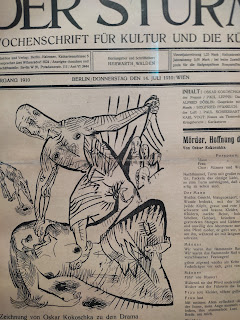

Three years later, in a drawing for Der Sturm, Kokoschka's sexually frustrated males were stabbing and killing their former objects of desire. An early treatise on toxic masculinity? An inspiration for Adolescence? Or simply exploitative titillation to sell a magazine? All of the above?

Oskar Kokoschka - Drawring for order, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer, Hope of Women) from the periodical Der Sturm (1910)

There's a wall hanging that talks about the advancement of female emancipation in the first decade of the 20th century, the bourgeois moral codes of the time (as expressed, it seems, in Frank Wedekind's 1891 play Spring Awakening), Sigmund Freud's work on repressed desires, and the increasing presence of women artists.

In 1903, the Austrain philosopher Otto Weininger released his misogynistic and anti-Semitic book Sex and Character that would, decades after Weininger's suicide in 1903 at the age of 23, be mined for propaganda by the Nazis. In it, Weininger proposed a pseudo-scientific argument for the preservation of what he saw as male genius. He believed that all of us are made up of both male and female qualities and that male aspects were productive, active, conscious, moral, and logical. While the female aspect is passive, amoral, alogical, and unproductive. It sounds like repellent bunk of the worst kind to any sane person now but Oskar Kokoschka, a once - and still - celebrated artist, was a fan.

Otto Dix - Lament (1913-15)

It's not impossible to see Weininger's influence in some of Kokoschka's, otherwise aesthetically impressive, work. Otto Dix, in his pen and ink Lament, is a bit more difficult to read. Lament features naked, anguished, women and because we know he would also go on to make a series of 'lust muder' paintings (depicting sexual homicide) it's hard to completely exonerate him from the same charges levelled at Kokoschka and Weininger. The Nazis weren't so keen on Dix though. He was displayed in their infamous 1937 Munich exhibition of 'degenerate art'.

Georg Baselitz, now 82 years old, is still with us. The curators of With Graphic Intent ponder if his untitled and hirsute looking ouroboros alludes to a sexual dominatrix or a primeval goddess of fertility but it's certainly got an uncomfortable sexuality about it. It's definitely not erotic and nor, one suspects, is it intended to be.

Georg Baselitz - Untitled (from the Whip Woman series) (1964)

It's a bit of a strange outlier, in a slightly strange show, in that it comes from about half a century after everything else on display. I suppose it helps the curators of the show tell the story that they want to tell. One name that crops up a few times is that of the Viennese writer Karl Kraus (1974-1936) who was widely regarded for his ridicule of the hypocrisy in Viennese society.

He campaigned for women's education and reform and for the decriminilisation of prostitution yet at the same time was also a fan of Weininger and believed that an effeminate modern society was a mark of cultural degeneracy. He feared he was living in what he called a 'vaginal era'. The pussy! He compared the 'hysteria' of women to mould growing in a damp room, and said that "to be seen on the street with a respectable woman may be compromising but to conduct a conversation with a young woman about literature borders quite simply on exhibitionism".

The Andrew Tate of his era, he nonetheless was taken seriously and admired by the likes of Oskar Kokoschka. How these ideas were allowed to go unchecked and even propagate makes for an interesting cultural study and one sadly still relevant to the era of culture wars we find ourselves living in. So it's a confusing pivot that only one half of the show is dedicated to it and the rest is given over to, admittedly impressive and pioneering, woodcuts and graphite drawings that aren't even remotely about that subject.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Dr. Ernst Gosebruch (1915)

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff - The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1918)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were, along with Max Pechstein and Emil Nolde, at the heart of the Die Brucke (The Bridge), a group devoted to the creative potential of printmaking. Dr Ernst Gosebruch, who looks here like a flayed C3PO auditioning for a role in Hellraiser, was a director of the Folkwang Museum in Essen and an early patron of Kirchner.

What he thought of Kirchner's startling depiction of him I don't know. Schmidt-Rottluff's The Miraculous Draught of Fishes was inspired, like Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon from eight years earlier, by African masks the artist had seen in museums and uses a block cut from planks of fir found in the forests of Lithuania where Schmidt-Rottluff had served in World War I. The image shows St Peter and his fellow fisherman being recruited as apostles of Christ.

Wassily Kandinsky, usually seen as a Russian artist, was born in Moscow in 1866, but he spent many years working in Germany and no doubt inspired, and was inspired by, art and artists there. His brush and black ink Untitled work is, clearly, far more abstract than anything else on display but, much as I like Kandinsky, I'm more taken by Paul Klee's Children and Crows from 1932.

Paul Klee - Children and Crows (1932)

Klee, famously, liked to 'take a line for a walk' and loved to celebrate childlike innocence and joy. Like other Expressionist artists, he believed that children were uncorrupted by the materialism of the modern world and while working as a teacher at the Bauhaus art and design school he encouraged his students in childlike play as a way of honing their creative instincts.

The srcibbly characters in Children and Crows look like a potentially terrifying, or possibly friendly, army of soft toys that have come to life and are marching forwards into an uncertain future. After all, it was made in 1930s Germany!

Conrad Felixmuller - Portrait of Walter Kunzel (1922)

Peter Trumm - Portrait of Reinhard Piper (1924)

Compared to the free, and experimental, approaches of both Klee and Kandinsky, the two portraits by Conrad Felixmuller and Peter Trumm are all a bit meat and potatoes. They're well made, especially - I think, Trumm's Reinhard Piper - a man who published Kandinsky, but they serve, for me, more as examples of what woodcuts used to look like and not what woodcuts could be.

They'd have been an underwhelming way to end this blog so I've opted for Heinrch Campendonk's Nude with Rooster because it manages to combine the two slightly disparate themes within With Graphic Intent. There's a tiny bit of female objectification (or so it initially seems) to it but it's also a pioneering piece of art made not in the case of paper but on a postcard.

It seems to find the lost ground between Picasso's Cubism and Kandinsky's total abstraction and it was actually used as something of a love letter. Campendonk sent the postcard to his future wife Adda Deichman with, on its reverse, the inscription "if I could just tell you once how much I love you ... I must come soon!". A nice message to end on I think.

No comments:

Post a Comment