Crikey! Don Letts has lived quite the life. It's quite remarkable how much of it William E. Badgley manages to cram in to his (roughly) ninety minute Rebel Dread but the fact he does means the film zooms along at breakneck speed. There's barely enough time to take stock. Which, you suspect, is exactly the way Letts likes it.

His life has been one lived fast and lived, often, impetuously. It's also been one of quite remarkable success and one full of enough fantastic anecdotes, often hilarious, sometimes poignant, that you find yourself hooked on every single word he says.

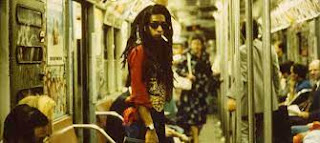

Which, in Rebel Dread, are quite a few. Letts sits in a kind of director's chair, with THE DON stencilled on the back, smoking, swearing, and taking calls from his daughter Liberty as he tells a story that begins in Brixton in 1956 and moves through the punk scenes of Chelsea and the ganja heavy post-Roxy parties of Forest Hill (my manor) to eighties Jamaica at the time of civil war and New York City around about the time that hip-hop was being born.

During that time Letts has been a DJ, a film maker, a musician (of sorts), a lyricist, a dancer, a dandy, and, more than anything else, an enthusiastic liver of life. A man who does not let an opportunity escape him. He's also been a lover of many women and a father of a few kids and, on these final points, he admits that sometimes he's been a bit of a dick.

Footage, and photographic evidence, show Letts to be a kind, caring father but his career, his lust for creativity, have, in the past, made him an absent father and an unfaithful lover. These are things he apologises for with no equivocation whatsoever but when it comes to his film making and his love of music he, it would appear, has no regrets at all.

Helping Badgley, and Letts, tells Letts' story there's an impressive collection of talking heads. Former Clash men Mick Jones and Paul Simonon, John Lydon, Jazzie B, Norman Jay, Daddy G of Massive Attack, and the journalist Vivien Goldman share screen space with less celebrated figures like Leo Williams of Dreadzone, former NME journo Chris Salewicz, Letts' brother Des McCoy, and Letts' first girlfriend Jeanette Lee.

Lee, who went on to become a member of Public Image Ltd, is Letts' gateway into the punk subculture. Before that he'd been a Beatles obsessive and a Bowie fan unafraid to rock an androgynous look on Brixton's frontline, Railton Road, in the mid-70s.Much to the consternation of his brother Des and others.

But it is in the world of The Sex Pistols, The Slits, and, most of all, The Clash that Letts found his true calling. In the early punk days there were no British punk records for DJs to play between bands so Letts filled the space with dub and reggae tunes, creating a bond between the two movements that lasts until this day and, for me, helping ensure that most punks took a firm anti-racist stance.

There's some of the stock punk footage you'll have seen a hundred times before (Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones swearing at Bill Grundy, Shane MacGowan pogoing in his Union Jack jacket) but there's also great footage of The Slits pissing around on tour with The Clash and Siouxsie and the Banshees playing a discordant live version of the Captain Scarlet theme tune.

Letts tips his very big hat to the influence of Lee but also to Strummer, Jones, Simonon, Lydon, Malcolm McLaren, and Vivienne Westwood (Letts worked at Acme Attractions on the Kings Road in Chelsea, a shop inspired by McLaren and Westwood's Let It Rock boutique). When The Sex Pistols break up and Letts travels to Jamaica, for the first time in his life, with Lydon and Richard Branson he's approached by many of the leading reggae artists of the day (I-Roy, U-Roy, Prince Far I, Lee 'Scratch' Perry). All hoping to get signed and make some money out of their amazing music.

More than any of these though, it's Bob Marley who proves a major influence on Letts - and Letts on Marley too. When Marley first encountered the 'dirty' punks of London he wasn't too impressed and it was Letts who explained to Marley how these (mostly) white kids were as disaffected and disenfranchised as Marley and his fellow reggae musicians were back in Jamaica.

As early as 1977, Marley (with Lee Perry on production duties) had released Punky Reggae Party. Reggae remains a mainstay in Letts' life (and still makes up the bulk of his DJ set) and he talks, passionately, about the effect Perry Henzell's 1972 film The Harder They Come had on him as a teenager. In a country, the UK, where black people rarely appeared on television, where sus laws saw people of colour specifically targeted by racist police forces, where crude National Front graffiti could regularly be seen daubed on walls and fences, where just four years earlier Enoch Powell had delivered his Rivers of Blood speech, to see a film that told the story of black people's lives was exhilarating and woke Letts, and others, up to the possibilities available to them.

Having been all but electrified by witnessing The Who live, Letts knew that music, something he still calls the "elixir of life", was where he needed to be and when he bought his first video camera he found his niche. He'd be the man who'd go on to document, at first, the punk movement before going on to make films about such unique and inspiring figures as Gil Scott-Heron, George Clinton, and Sun Ra.

He was even invited to Namibia in 1990 to capture that nation's celebrations as they achieved independence from South Africa. When Mick Jones was kicked out of The Clash, Letts became a key member of Big Audio Dynamite and a pioneer of sampling. When he left B.A.D. he formed Screaming Target (named after a Big Youth tune) and though they only lasted for one album, 1991's Hometown Hi-Fi, two of its members, Leo Williams and Greg Roberts, went on to form Dreadzone.

Letts comes across as much an enabler of other's creativity as creative wellspring himself. From The Slits, Black Grape, and Musical Youth to New York graffiti artists and The Beastie Boys, Letts always seems to be lurking in the background somewhere. It's not bad for the boy who hated school so much he set fire to his desk, for the adolescent who exchanged his entire (and incredibly comprehensive Beatles collection) for a big "fuck off American car" at the height of punk, and for the reggae DJ who spent long evenings smoking weed with Billy Idol in SE23.

It wasn't the career path that his parents, his dad was quite remarkably called St Leger Letts - named after an annual horse race in Doncaster, would have expected for him but it is one that has brought him fame and respect and, more than anything else, has given him what appears to be a life full of joy and packed with rich and rewarding experiences. Despite one or two slightly odd dramatisations, Badgley's film manages to capture this and to give us greater insight into Letts than ever before. What his motivations are. What his methods are. As Letts himself puts it right at the end of the film:- he does what he loves, he doesn't worry too much about money or success, and tries his very hardest, at all times, to not be a cunt.

No comments:

Post a Comment