"If there are those who want to remember the legacy of the Confederacy, if they want monuments, well, then, my body is a monument. My skin is a monument" - Caroline Randall Williams.

Four Nocturnes (2019)

The powerful words of the Nashville poet, academic, and author Caroline Randall Williams prick the disingenuous balloon of all those who say that statues, like the one of Edward Colston pulled down and thrown into Bristol Harbour last summer, teach us about the history of colonialism. They don't. They say nothing about what it really meant and, instead, celebrate slavers and mass murderers.

You don't have to open your eyes very wide to see that the history of colonialism, slavery, and racism are all around us. Certainly not in Bristol where roads like Blackboy Hill and Whiteladies Road exist (although there is a view that both these thoroughfares are actually named after pubs - though why did the pubs have these names?) and where the city's mayor Marvin Rees, who has spoken passionately, knowledgeably, and with consideration about the Colston statue and the city's history, is the son of a black Jamaican father and a white British mother.

A background he has eloquently delved into for BBC2's excellent documentary Statue Wars:One Summer in Bristol. The Ghanaian born British artist and theorist John Akomfrah has got a few years on Rees and his position, as an artist rather than as an elected official, is necessarily different. His role is not to provide direct answers to topical, yet depressingly evergreen, issues - but to ask questions and with his current exhibition, The Unintended Beauty of Disaster, at London's Lisson Gallery that is just what he does.

Four Nocturnes (2019)

Four Nocturnes (2019)

Four Nocturnes (2019)

What those questions are, however, is not always very clear. A handful of photo text works accompany two lengthy multi-screen video installations and though they're engaging to look at, it's uncertain exactly what message we are intended to take away.

So far, so art. While Akomfrah comes good on his promise to make us consider themes of post-colonialism, black British identity, and the climate crisis it's not always clear what point he is making about these things. Four Nocturnes, the longest and largest of the video pieces, use Africa's declining elephant population as a narrative, and allegorical, device to tell stories of how humans are destroying the planet, destroying each other, and, ultimately, destroying themselves.

Films of elephants majestically sweeping the plains or being put to use as working animals mix with meditations on nature, faded sepia photographs, and a lot of weather. At one point some dude shows up wearing an elephant mask which, aesthetically pleasing and somewhat amusing though that is, seems to underline the point that our future is tied up with that of the animals we share the planet with only too clearly.

We Are The Proof (2021)

Our Skin Is The Monument (2021)

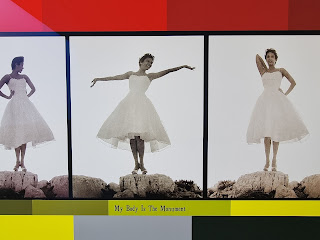

My Body Is The Monument (2021)

The next room is given over to some rather pleasant and colourful images of Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge in Otto Preminger's 1954 film Carmen Jones. Belafonte and Dandidge, Akomfrah seems to be saying, are the real life monuments we need. Not statues of slave owners.

It's a nice point and the two actors look, of course, young and indefatigable. "The Monuments of Being" went further and showed that black, and African, people have long been enshrined in statuary around the world and have long been celebrated. If, often, not in the places we think to look - and not in the places that modern society deems to be at the top of the hierarchy of imagery.

"The Monuments of Being" (2021)

"The Monuments of Being" (2021)

"The Monuments of Being" (2021)

"The Monuments of Being" (2021)

Triptych (2020)

Triptych (2020)

Finally, there is a film with the simple, matter of fact, title of Triptych that, like Four Nocturnes, has a lof of weather, a lot of sea, and a lot of nature - but is interspersed with a variety of people, and faces, who represent the multi-faceted experience of being black in the world right now. It's meant as a homage to Max Roach's radical jazz album of 1960, We Insist!, which prefigured the Civil Rights and anti-apartheid movements.

Though you'd unlikely be able to discern this were it not for the leaflet handed out on entrance to the Lisson. Akomfrah wants you to know that any of these friendly, curious, inquisitive, or even impenetrable faces could easily have been, or still become, the next George Floyd or the next Breonna Taylor. The fact that his selection of 'sitters' almost seems random seems quite apt - as police brutality and racism towards black people does not consider individuality either, only race.

Though the words of Caroline Randall Williams, Marvin Rees, and many many others speak louder and more powerfully than the work of Akomfrah, racism is a societal cancer that should have been removed a long long time ago. John Akomfrah's The Unintended Beauty of Disaster does its bit to address that and John Akomfrah, as an artist, has done more than his bit to address that throughout a long career. Until racism is extinguished, there can never be enough works of art addressing its poisonous nature and coming at it from all angles. If politicians won't lead (and with honourable exceptions like Marvin Rees, they won't) then it is falls on artists, poets, and every one of us to do so.

Triptych (2020)

Triptych (2020)

Four Nocturnes (2019)

Four Nocturnes (2021)

Four Nocturnes (2021)

Four Nocturnes (2021)

No comments:

Post a Comment