Jesus Christ is everywhere in the National Gallery's current Mantegna and Bellini exhibition. There are dead Christs, living Christs, Christs that are somewhere between life and death, baby Christs, adult Christs, realistic looking Christs, unrealistic looking Christs, and Jesus in a Limo.

Well, not the last one - obviously. But, Christ on a bike, that is one hell of a lot of son of Gods to have to take in on a Monday afternoon. I reckon 15c Venice would have been even busier Christwise though. They were religious times - and Venice was a religious city, as most (all?) were in Europe at the time. Far be it from me to chat shit about Renaissance art but there are times when you begin to wonder if they didn't overdo the God a little bit. Renaissance complacence is a thing, you know.

Anyway, this particular Renaissance tale begins when Padua's new sensation Andrea Mantegna marries Nicolosia Bellini, daughter of Jacopo, sister of both Giovannia and Gentile, and, as such, joins one of the most respected and established of Venetian art dynasties.

There's a couple of Jacopo's works early on but there's nothing by Gentile and nothing even about Nicolosia. This show is all about the relationship between Andrea Mantegna and his brother-in-law Giovanni Bellini. How they influenced each other, what each of their strengths was, and what happened when, eventually, they went their own separate ways? What marks did they make on each other and the way they painted? I'll 'fess up straight away that I won't be able to tell you. I'm not E.H.Gombrich.

Andrea Mantegna - Presentation of Christ at the Temple (c.1454)

There's a lot of comparing and contrasting works of, and about, the same subjects that both artists made and, in the first instance, there is the somewhat bizarre example of Bellini 'tracing' round one of Mantegna's earlier works, Presentation of Christ at the Temple, and then bunging a couple of extra figures in on each flank. Bellini's Jesus has got a smaller head, Joseph's coat (of not so many colours after all) is more purple but, other than that, it's uncertain as to why this work was executed - and there's little here to tell us. There's a Saint Jerome by each of 'em too. Marginally more different than their Christs but hardly to a noteworthy degree.

I suppose when dealing with Christianity (as with all other religions) looking for logic is beside the point. Religious art is bonkers, surely, for the simple reason that religion is utterly bonkers. That doesn't make it uninteresting. As a confirmed atheist of many decades standing, I appreciate churches for their architecture, gospel music for the way it makes me feel, and religious art for its skill. What underpins them all, for me, is not so much God, as the human capacity for invention. In fact, I'd go so far as to say the invention of God is perhaps one of the greatest, and sadly one of the most deadly, pieces of art us humans have ever come up with.

I digress, it's my blog -I'll do as I please. We're informed on entry to the exhibition, and we can soon see for ourselves, that Mantegna was big on invention, storytelling, and bringing 'life' to classical antiquary whereas Bellini had a less showy talent. Light, colour, and working up of the landscapes were where his strengths lied.

I digress, it's my blog -I'll do as I please. We're informed on entry to the exhibition, and we can soon see for ourselves, that Mantegna was big on invention, storytelling, and bringing 'life' to classical antiquary whereas Bellini had a less showy talent. Light, colour, and working up of the landscapes were where his strengths lied.

Giovanni Bellini - Presentation of Christ at the Temple (c.1470)

Andrea Mantegna - Saint Mark the Evangelist (c.1448)

Perhaps being born into virtual aristocracy gave Bellini the confidence, and the security, to work with small gestures and, perhaps - just perhaps, Mantegna's more lowly birth made him more determined to make grand statements. When nobody is listening to you, it's easy to see why shouting may seem the only viable option. Or, more likely - though no good for the word count, they were just both good artists with different styles.

Though not that different. That's the thing when you go back to this era. Unless, you've got a very very discerning eye (and, sadly, I do not - I fake it) it's really difficult to tell your Leonardos from your Michelangelos, your Piero della Francescas from your Fra Angelicos, and, indeed, your Mantegnas from your Bellinis. I soldiered on in the hope of the kind of divine revelation it seems likely both these artists would have cited as behind their work.

It didn't come with Mantegna's Saint Mark the Evangelist, just a bloke with a beard, but I was more impressed with both his, and Bellini's, take on The Agony in the Garden. It's hard to tell with my crap photos taken off a computer screen (photography was not permitted in the exhibition, unlike in the same gallery's recent Courtauld Impressionists exhibition) but you can probably just about make out that Bellini left much more room for the background whilst Mantegna focused more on the figures.

Though not that different. That's the thing when you go back to this era. Unless, you've got a very very discerning eye (and, sadly, I do not - I fake it) it's really difficult to tell your Leonardos from your Michelangelos, your Piero della Francescas from your Fra Angelicos, and, indeed, your Mantegnas from your Bellinis. I soldiered on in the hope of the kind of divine revelation it seems likely both these artists would have cited as behind their work.

It didn't come with Mantegna's Saint Mark the Evangelist, just a bloke with a beard, but I was more impressed with both his, and Bellini's, take on The Agony in the Garden. It's hard to tell with my crap photos taken off a computer screen (photography was not permitted in the exhibition, unlike in the same gallery's recent Courtauld Impressionists exhibition) but you can probably just about make out that Bellini left much more room for the background whilst Mantegna focused more on the figures.

Andrea Mantegna - The Agony in the Garden (c.1455-6)

Giovanni Bellini - The Agony in the Garden (c.1458-60)

They're both good paintings and I'd find it hard to pick a winner. But when it comes to their take on the crucifixion, Mantenga wins hands downs. Bellini's crucifixion (which I've not included) is a fairly bog standard affair, a skinny Christ looking a bit forlorn. But Mantegna's really gone to town with his. Spectacular hills and skies frame the sight of Jesus and the two 'robbers' nailed up as crowds in spectacular robes, and even a horse, mourn or observe their death. On the ground sit a group of what I presume to be guards, or some other minor officials, who are so disinterested in the death of Jesus Christ they're having a game of dice. If you think it's a shame they're missing such a pivotal event then don't worry. Remember, he would rise to die again. Repeats. Even back in those days.

Andrea Mantegna - The Crucifixion (c.1456-9)

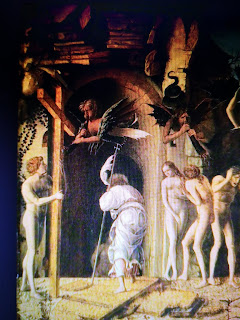

Giovanni Bellini - The Descent of Christ in Limbo (c.1475-80)

Religious scene follows religious scene and I start coming round to them, you can see how people get sucked in, but I think that's more down to the quality of the art than any 'message' inherent. We learn that although Mantegna was 'self-made' he studied Donatello intensely, we see in the Pieta - the Christ of constant sorrows - that Mantegna seemed to get more of a kick out of torturing Jesus than Bellini did, and some cat called Marco Zoppo keeps rocking up.

Zoppo was a Bolognese contemporary of Mantegna and he seems to be something of a third wheel in the bromance between Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini. A bromance that was to end, or at least to be continued from afar, in 1660 when Andrea Mantegna upped sticks and left Venice for Mantua (a beautiful, if rather dull, city I had the pleasure of visiting back in 2014) while Bellini stayed on in the City of Bridges, La Dominante

Giovanni Bellini - Pieta (c.1457)

Andrea Mantegna - Samson and Delilah (c.1500)

Andrea Mantegna - The Death of the Virgin (c.1460-4)

Here their art diverged too. Though traces of each other's influences remained, as they so often do. The 'triumphs' Mantegna painted to celebrate Julius Caesar's victory over Gaul in Mantua's Ducal Palace are so huge that there's barely enough room to stand back far enough in the gallery to take them all in. This is palatial art in all senses of the word and it features a parade of elephants, elaborate processsions, and golden candelabras.

Yet Mantegna, as if remembering Bellini, was turning his hand to smaller, more intimate, personal work to. Witness, for example 1500's Samson and Delilah. The classic statues of the lovers greyed out against a fiery, bright red background as if the passion has left their bodies and gone to nature. It was a landscape, us visitors were informed, inspired by the Early Netherlandish art of Jan van Eyck.

Bellini, it seemed, was casting an envious glance back - and in The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr we can see his canvases getting larger and his subject matter becoming grander. Although it was with The Resurrection of Christ that he seems to have really given free rein to his imagination. Look at the size of the Christ on that!

Giovanni Bellini - The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (c.1505-7)

Giovanni Bellini - The Resurrection of Christ (c.1475-9)

Andrea Mantegna - Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue (c.1500-2)

Giovanni Bellini - Doge Leonardo Loradean (c.1501-2)

He was still capable of small scale, contemplative, portraiture though and in the case of his famous Doge Leonardo Loradean he even allowed himself a rare lapse into the secular. Loradean was the 75th doge (chief magistrate) of Venice and, according to Wikipedia - you don't think ALL of this is stored in my brain do you?, the most important the city ever saw. I love the way the blue background juxtaposes against his solemn and sombre face.

Titian and Dosso Dossi were called in, after the fact, to add a few details to Bellini's Feast of the Gods which may have a 1930s Disney colour scheme going on but certainly seems to show one hell of a party going down. There are people balancing saucers on their heads, a woman helping herself to a libation, a pie eyed chap in a fetching red sash staring gormlessly out at us, and one dude seems to have the hind legs of an ass. We've all been there....

Giovanni Bellini (with later additions by Titian and Dosso Dossi) - Feast of the Gods (1514-29)

Giovanni Bellini - The Drunkenness of Noah (c.1515)

....and we've all woken up the next morning like Noah (above). He's gonna have a sore head - and it's still over four centures before ibuprofen will be discovered. A wasted pre-Flood Patriarch wouldn't normally be one of the most identifiable paintings in an exhibition but such is the sheer insanity of Christianity (I mean, at times you start to wonder if they just made it all up) that I found myself feeling quite tempted to get as messed up as Noah (and I hadn't even saved all the world's animals from drowning). I didn't though. I got the train home, scoffed a pack of Mini Eggs (that's an Easter thing so that makes me observant, right?), and then tried to fit a narrative around a story that really doesn't make any sense but has certainly thrown up some wonderful and intriguing art.

I was flippant in my assessment, and will continue to be rude about religion - I'm not killing religious people like they have (and continue to do so) with non-atheists, but out of respect for the 'faith' of those who do believe I'll leave the last paragraph to Giorgio Vasari. A learned scholar and respected source on Renaissance art no doubt, but also a brown noser of the highest order who, of Mantegna, has this to say:-

"Andrea was so kind and lovable that he will always be remembered not only in this country but all over the world. He was rightly praised by Ariosto at the beginning of Canto XXXIII where the poet places him among the greatest painters of his time: Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino".

Vasari did not give Giovanni Bellini a chapter. Ouch!

I was flippant in my assessment, and will continue to be rude about religion - I'm not killing religious people like they have (and continue to do so) with non-atheists, but out of respect for the 'faith' of those who do believe I'll leave the last paragraph to Giorgio Vasari. A learned scholar and respected source on Renaissance art no doubt, but also a brown noser of the highest order who, of Mantegna, has this to say:-

"Andrea was so kind and lovable that he will always be remembered not only in this country but all over the world. He was rightly praised by Ariosto at the beginning of Canto XXXIII where the poet places him among the greatest painters of his time: Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino".

Vasari did not give Giovanni Bellini a chapter. Ouch!

No comments:

Post a Comment