"No African artist has done more to enhance photography's stature in the region, contribute to its history, enrich its image archive or increase our awareness of the textures and transformations of African culture in the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st than Malick Sidibe" - Robert Storr, MoMA curator.

Malick Sidibe died in Bamako last year. It's not certain if he was 80 or 81 years old at the time of his death but it does seem apt that he passed away in Bamako, the largest city and capital of Mali, which had been at the very centre of his work since he opened his first studio there back in 1962. It also makes Somerset House's current exhibition of his work very timely, if perhaps a little overdue.

Despite, or perhaps because of, being blind in one eye Sidibe became known as 'The Eye of Bamako' and in this guise he managed to immerse himself in the city's action whilst, simultaneously, retaining an almost invisible presence. With his Kodak Brownie he was Mali's only travelling photographer and, in a pleasing parallel with William Eggleston (who I wrote about last year), he made his subjects the things that were around him anyway:- graduation ceremonies, beach parties, and nightclubs. Here we can see two young music fans proudly brandishing their vinyl in 1964's Les fans en James Brown.

The above and below shots, Danseur meringue and Au mess garnison, both come from 1964 too. They're from Sidibe's Tiep a Bamako/Nightlife in Bamako series which ran from '63 to '65. They capture something of the innocence of youth but also the thrill and excitement of living in a new nation, Mali having achieved independence only in 1960.

Sidibe would cycle around town taking his photos during the afternoon and evening and then stay up all night printing them out so that a selection would be hanging on the walls for perusal when his subjects arrived a day later to choose their favourite.

During the seventies Sidibe worked on his Au Fleuve Niger/Beside the Niger River series. Again these photos speak of youth, possibilities, and fun. The group photo, Un soiree a la chaussee was taken in '76 and the young lads, once more, proudly showing of their vinyl in Pique-nique a la chaussee come from '72. With all this music on show it's apt that the shop at the end of the exhibition stocks records.

Even more welcome, in fact an absolute joy to listen to, was the soundtrack as you walked through the gallery. Rita Ray has curated a selection appropriate to the time. Not just from Mali but from other African countries like Senegal, Cameroon, Ghana, South Africa, and Nigeria. To hear the likes of Ali Farka Toure, Youssou N'Dour, Miriam Makeba, Boubacar Traore, Manu Dibango, Fela Kuti, Salif Keita, ET Mensah, and the Rail Band doesn't detract from the photography at all. In fact it complements it, helps you to imagine what sort of music these young men and women would have been listening to on their pique-niques. There's even recordings of The Jackson 5 playing live in Dakar.

Sidibe has been quoted as saying "Music was the real revolution. Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close."

Sur les rockers a la chaussee (1976, below) is one of the very best shots in a very good collection. The couple in this photo look happy and proud. No doubt part of this is because they're having a fun day out by the riverside. But I like to imagine, also, that in Mali, in the 70s, it was quite a rare opportunity to get your photo taken and one they were only to pleased to take advantage of. The smile of the young lady and the gleaming belt buckle of the young man draw your eyes to the centre of the photo. It's very simple but often beauty is found in simplicity.

Sidibe wasn't always out at parties or hanging around the Niger river. He also ran his own studio in Bamako from the sixties to 2001. Studio Malick was based in the Bagadadji quarter of the city for the expedient reason that it was one of the few areas to have electricity.

The photos he took there were, necessarily, more posed than natural. Some sitters took the chance to get dolled up in their glad rags. Ten gallon hats and seriously loud shirts feature strongly. People would even bring in their donkeys and goats to pose alongside. Even if they didn't bring clothes or props with them Sidibe kept two dressing up boxes, one full of hats, the other ties, in the studio for his subjects to put to use.

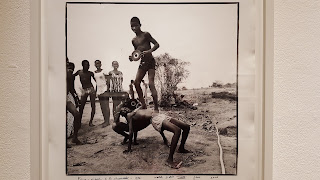

Sidibe said "It was like a place of make believe. People would pretend to be riding motorbikes, racing against each other. It was not like that at the other studios". What exactly was going in Yokaro (1970, below), however, I've no idea but it's certainly a very strong look.

Amis du Espagnols from '68 is almost as eye-catching. The guy at back left surely sporting the largest, if not the nattiest, sombrero in all Bamako. Below them, in Les jeunes bergers peulhs (1972) the gentlemen in the middle proudly shows off his state of the art boombox. Despite the rather stiff poses it wonderfully captures the time. As does all Sidibe's work.

With the Western hegemonic as it was (and, in many ways, still is) it hardly comes as a surprise that worldwide recognition didn't come until the 90s when Andre Mangin, the curator of this show, met Sidibe in Bamako. By 2007 Sidibe had won the Golden Lion in Venice, the first African to do so. It was one of many awards he went on to reap.

This was a neat little exhibition - and a free one to boot - so if you find yourself anywhere near The Strand or Fleet Street pop into Somerset House. There's an ice rink there at the moment and there's a beautiful, serene, courtyard as well as views across the Thames at all times. Sidibe's snaps won't delay you for very long but they will definitely be worth your time.

No comments:

Post a Comment