Even if I could remember something it'd probably just be lying in a cot crying or shitting my nappy (not much changes eh?) because that was my lived reality. Oh, and getting burnt so badly by a pan of boiling milk that the scars still show to this day.

I've never really got the fascination/fetishisation of this decade above all others. I'm sure it was great at the time and all that but this wilfulness to peer back through rose tinted spectacles at a past that never was is one of the English people's less appealing traits. In the same way, and for the same reasons, as a Keep Calm and Carry On poster, a young man dressed as an Edwardian strongman, or a Brexit campaigner posing in a pub with a pint of nut brown ale.

But in the name of research I found myself digging out my best Austin Powers fancy dress outfit and having the Mini Cooper sprayed up like a Union Jack. I'd even taken the trouble to get a helicopter to film me driving over Tower Bridge from a jaunty angle to a John Barry soundtrack. Groovy!

Obviously I didn't do this really (lol, soz 4 the epic bantz!) but, instead, I wore my normal clothes on the 63 bus to Elephant & Castle and took the Bakerloo line to Oxford Circus and then walked down to The Photographers' Gallery where they were hosting Terence Donovan:Speed of Light. Which hopefully explains my somewhat lengthy preamble. As a major chronicler of the era Donovan can take a lot of credit (or, indeed, blame) for the way we view it now.

He was born in 1936 and committed suicide (seemingly after reacting badly to prescribed drugs) sixty years later. He lived in Stepney all his life and knew the area better than most cabbies. In 1959, aged 22, he opened his first studio in West London. His first commission was a still life photograph of a sponge cake. Very disappointingly it's not in this show.

Donovan claimed his eye, as restless as the great metropolis itself, scanned at the speed of sound. Quite a boast yet he was entitled to feel pleased with himself. His ascendancy as a fashion photographer coincided with a more overt, more sexual, certainly more heterosexual gaze. Whereas earlier practitioners had been borderline aristocracy and predominantly homosexual Donovan, along with his contemporaries David Bailey and Brian Duffy, were working class and, to use the parlance of the time, fond of the birds.

Walls of contact prints attest to both this and the cool jazz crowd they were down with. They feature Jean Shrimpton, Susan Hampshire, Joanna Lumley, Roland Kirk, and, er, Michael Heseltine. Yes, that one.

Tom Wolsey was art director of Man About Town magazine and he gave Donovan one of his first big breaks working together with Don McCullin the much respected photojournalist whose images of war and urban strife portrayed a very different world to the leisured classes Donovan both observed and mixed with.

He wasn't completely isolated in an ivory tower of haute couture and beatnik bliss though. Whilst his colour works for Elle, Vogue, London Life, and Brides magazine raked in the cash his black and white photography hewed closer to McCullin's documentarian and realistic oeuvre. Strippers and self-confessed 'layabouts' aren't quite Biafra or the Vietnam War but they do point to a greater versatility than I'd previously been aware of.

He formed a close bond with fellow working-class-London-boy-made-good Vidal Sassoon and took the hairstylist's advertising shots from the sixties and beyond. Other fashion shoots made good use of unlikely locations. Here's Grove Road Power Station in St.John's Wood. It was demolished in 1973.

He was just as happy working in a grey Victoria Park or in the bleak evening light of Deptford as he was with the stars of the era. Contrast the power station above with the shots, below, of Jimi Hendrix, Cathy McGowan and Kenny Lynch, Sarah Miles, and Julie Christie.

Unlike some once the sixties were over he moved on. The seventies and eighties saw portraits of characters as disparate as Roald Dahl, Max Wall, Norman Wisdom, Ian Dury, Jimmy Greaves, Elvis Costello, and Henry Cooper.

Country Life, Harpers & Queen, Tatler, and Cosmopolitan all came calling. Princess Diana sat for Donovan four times and he adapted, seemingly and unsurprisingly with great enthusiasm, to the supermodel era. Both Naomi Campbell and Cindy Crawford posed for him.

He turned his hand to pop videos too. Malcolm McLaren's Madame Butterfly and Robert Palmer's Addicted to Love being his most widely recognised works in that genre. There's a very sexy picture of Vicky Ferda in the Park Lane Hotel, Piccadilly from that time and, perhaps a little less titillating for you, shots of both Donald Sinden and Kenneth Williams.

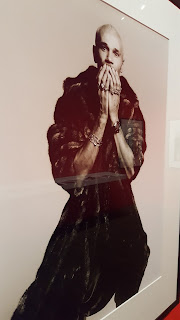

In 1996, for GQ magazine, he took the series National Anthems focusing attention on the musical heroes of the day. It turned out to be one of his last commissions and The Photographers' Gallery have a room devoted to his prints of Jarvis Cocker, Jazzie B, Sean Ryder, Terry Hall, Mark E Smith, Goldie, Lemmy, Wilko Johnson, and Underworld.

Terence Donovan's not responsible for the ongoing obsession with the sixties. He was, clearly, a man very much cut from the cloth of the era but he was talented enough to adapt and to continue at the top right up until his untimely demise.

The Photographers' Gallery show is a fitting reminder of a career cut short and a major talent to boot. Despite my earlier protestations I thoroughly enjoyed it.

No comments:

Post a Comment