"Would you rather watch six hours of Teletubbies or six hours of porn?"

It's not a question I've ever heard asked before. Nor is it one I've ever pondered. But it was the final question of the Q&A section in last night's Skeptics in the Pub - Online talk, Ban this sick filth! Behind the scenes at the British Board of Film Classification, and it was one that former BBFC examiner and speaker Jim Cliff was unable to answer.

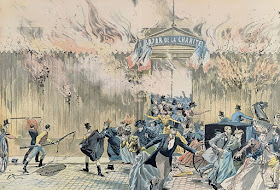

It was the only time in the evening Cliff struggled for words. A knowledgeable, articulate, and enthusiastic speaker, helmed by host Dave Jenkins of Coventry Skeptics, Jim Cliff began by taking us to Paris, back in May 1897. Eighteen months after the Lumiere brothers, Auguste and Louie, had staged the first public screening of a motion picture there was a charity event, the Bazar de la Charite, that ended in disaster and the loss of 126 lives when one of the key attractions, a cinematograph installation, caught fire.

Fires in the early days of cinema were not uncommon though rarely, if ever, this deadly. Two factors were at play. Firstly, cellulose nitrate - then used for film - was actually an explosive. Secondly, there were no custom cinemas yet built in those early days of the movies so films were screened in fairgrounds, shops, and, in Paris 1897, a large wooden warehouse decorated with cardboard and cloth.

This tragedy was still in the forefront of minds when, in 1909, in the UK, the Cinematograph Act was passed in which buildings that intended to show films to the public needed to be licensed. It seems that some councils chose to interpret this new law in more inventive ways than others and soon they were deciding not just where films could be shown but what films and when.

When, in 1912, the Daily Mail got its knickers in a twist about Sidney Olcott's From the Manger to the Cross, a film that told the life story of Jesus and received excellent reviews elsewhere, some got worried that the government would bow to pressure from the Mail and others and start intervening in film censorship. So one year later the industry formed its own board - the British Board of Film Censors - or BBFC.

Local councils were still ultimately in charge of what was, and wasn't, shown in their regions but, for the most part, decisions by the BBFC were simply rubber stamped - and that's still how it works today. For the most part. Exceptions are so noteworthy they become famous. Torbay Council banned Monty Python's Life of Brian from its release in 1979 until 2008 and David Cronenbourg's 1996 adaptation of J G Ballard's erotic psychological thriller Crash was banned by Westminster Council.

Forcing those who wanted to see it to walk nearly one hundred metres to the borough of Camden. These anomalies aside, things worked quite smoothly. Initially there were two categories for films. U for 'universal' - anyone could go to see it, and 'A' for adults - although still anyone could see those films too. The classifications were advisory only.

The release, and huge popularity, of James Whale's Frankenstein and Tod Browning's Dracula in 1931 caused a rethink and the next year a new H (for 'horrific') category was added. Decisions on what films were U, A, or H were, however, hardly scientific. They were made on the whims of examiners as were cuts to films and rejections of films outright.

Germaine Dulac's The Seashell and the Clergyman was a piece of experimental cinema, surrealist nonsense essentially but surrealist nonsense that was later recognised by the BFI as one of the most important feminist films ever made, but when the examiner saw it he decided that even though he had no idea what was going on, whatever was going on was probably objectionable.

Joseph Brooke Wilkinson had been Director of the BBFC from its instigation in 1913 until he died in office in 1948 and was replaced by Arthur Watkins. Watkins' main concern, in the post-war era, was teenage violence and juvenile delinquency. He rejected Laszlo Benedek's 1953 The Wild One (with Marlon Brando) as a "spectacle of unbridled hooliganism".

It wasn't until 1967 that the film was certified for viewing by a British audience beyond specialist film societies. Under Watkins, the H category was replaced by X and became mandatory rather than advisory. Following Watkins in the job was John Trevelyan who held the position of Director from 1958 to 1971 and, unsurprisingly perhaps, he was in position throughout the entire sixties, he presided over an era of liberalisation.

Under Trevelyan, audiences were treated to the first use of the word 'fuck' in films (Joseph Strick's 1967 Ulysses, loosely based on the James Joyce book), the first full frontal female nudity (Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup, 1966), and the first full frontal male nudity (Ken Russell's Women in Love, a 1969 adaptation of the D.H.Lawrence novel).

Perhaps to facilitate this, you now had to be eighteen, rather than sixteen, to view an X certificate film. Two new categories were brought in as well. AA and PG. AA would be, roughly, a 15 rather than an 18 and PG stood for Parental Guidance. The next notable Director of the BBFC was James Ferman whose reign spanned two and half decades from 1974 to 1999.

A year before Ferman started the job, the Bruce Lee film Enter the Dragon had started a Kung Fu craze and some of the weapons featured became, and remained for some of the time, popular with teenagers. Ferman introduced a blanket ban on both nunchucks and throwing stars in films. Even the scene in 1991's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II:Secret of the Ooze which featured Michelangelo using sausages as nunchuks was banned.

Ferman changed the C in BBFC from Censors to Classification and he brought in the system we still have now for ratings:- U, PG, 12, 15, and 18. Tim Burton's 1989 Batman being the first film to be awarded a 12 rating. The biggest change in Ferman's tenure though was, by far, the rise of the VCR. I can still remember the excitement when my dad brought our first Sony VCR back home and we slowed down Albert Tatlock on Coronation Street and made him walk backwards.

Not everyone's video fun was quite so innocent. With no restrictions on videos, soon films like 1980's Cannibal Holocaust were released. The makers of the film, looking to promote it as spectacularly as possible, sent a copy of the film, and a letter complaining about it, to Mary Whitehouse, the reactionary Christian activist who was a household name from the sixties to the eighties and railed against what she saw as falling standards in entertainment, social liberalism, and the permissive society.

They'd hoped, of course, to rile Whitehouse enough to get media coverage for their film and, to a degree, they succeeded. When Whitehouse was joined in her disapproval by another even more indefatigable campaigner for moral uprightness, the former Nazi supporting Daily Mail, the film, and others like it, became a major part of the national conversation.

The term 'video nasties' was coined, police raided video shops, seized video cassettes, and, in some cases, destroyed them. How it was decided which film was, or was not, a video nasty was unclear and most likely left to the whim of individuals. Which could not last. So, soon enough the BBFC started classifying videos too.

In 1999, Robin Duval took over as Chief Examiner at the BBFC and one of his first initiatives was to instigate a still ongoing public consultation process to find out what the public deemed offensive and what they deemed acceptable. These things are never static and the BBFC needed to move with the times. That could only be done with public consultation.

It was a smart move. When Jim Cliff joined, during this era, much of his training consisted of watching films that had set classification precedents and learning why they set those precedents. Parents, especially parents of small children, want to know what a U or PG film might feature and they need to be confident of consistency in the ratings.

Work, for Cliff and others, would consist of six hours randomly decided viewing each working day. An average day could see a session of Teletubbies, a session of pornography, a session of wrestling, and finally a few episodes of The X-Files. Almost all viewings would be done in pairs (potentially awkward with the grot) so that discussions could be had before final decisions were made.

Over the last twenty years, what we can see on our screens has been, for the most part, more overt. The only cuts made, now, for 18 certificate films are for scenes that break, or breach, the law. That's not always easily spotted. Pedro Almodovar's 2002 Talk to Her featured a bullfighting scene and though bullfighting is, sadly, legal in Spain, it is not in the UK. If you were to host, or partake in, a bullfight in the UK you would find yourself in fairly serious legal trouble.

A bullfight in the film would have been okay if Almodovar had simply filmed a bullfight in Spain and included it but because it appeared that the actress Rosario Flores had partaken in a bullfight specially for the film it fell foul of the censors. A cut was advised but Almodovar's team were able to get the decision reversed by proving that technology had been used to superimpose Flores' face on the face of an actual bullfighter. Bulls had been harmed but not to make the film. This fine point was enough to allow the scene to stand.

Sometimes nuance is even subtler. Alejandro Amenabar's 2001 film The Others was very creepy but it contained no sex or violence. It could have been a 15 as easily as it could a PG but was eventually passed as a 12 due to the 'tone' of the film. Tone is very important but it's hard to quantify. Some people are offended by swear words. Others couldn't care less.

The rule used to be you couldn't say 'fuck' in a PG film and one single f-bomb was permitted in a 12. Now, context is considered. The King's Speech (2010) sees Colin Firth stuttering out several 'fucks' but they're uttered in a non-aggressive way and are unlikely to offend or upset. The 1998 film version of The Avengers with Ranulph Fiennes and Uma Thurman was initially awarded a PG. They'd been hoping for a 12, they wanted at least some edge, so added a 'fuck' to the dialogue to get it bumped up.

Horror films that have not been scary enough to get an 18 rating have been known to throw in a gratuitous sex scene to get that all important X rating. Nobody, they wrongly imagine, wants to see a horror film that's got a 15 rating. Even though Poltergeist is a 15 (downgraded from an X) and is pretty damned creepy.

The on screen taking of drugs will get a film an 18 certificate if that drug taking is not seen to have a negative effect (quite unfair, drugs can be great fun). The 2003 Catherine Hardwicke film Thirteen featured a scene of solvent abuse in which nothing bad happened to either of the leads partaking so that, of course, had to be an 18.

Violence, too, has nuances when it comes to classification. Christopher Nolan's 2008 The Dark Knight featured lots of very impressionistic, cartoonish, violence that didn't look remotely real and couldn't realistically be copied by those viewing the film so it was given a 12 certificate. The Daily Mail (are you spotting a theme?) weren't happy and instigated a campaign of angry letters from their readers. Most of whom, of course, had not even seen the film.

Violence often comes hand in hand with gore and gore, too, relies on context. The Saw and Hostel films are almost pure gore and, of course, have 18 certificates but the silly, though very real, gore in Edgar Wright's 2007 Hot Fuzz was judged to be as comedic as it was horrific, bringing the rating down to a 15.

Another area of concern are 'imitable techniques'. That's things in films that, if you copied them, could be harmful to you and/or others. When David Fincher's Fight Club (1999) showed the audience how to make napalm it was fine. Because they showed the audience incorrectly. Another film that showed the audience the correct way to make napalm couldn't be allowed a release.

Which is fine. There are bound to be parts of the Internet where you can discover how to make weapons that can be used in terrorist acts but putting that up on the big screen for public entertainment isn't right. Although, in trying to doing the right thing in his job, Jim Cliff confesses, tongue only slightly in cheek, that he may have inadvertently been responsible for the Pizzagate shootings in Washington D.C.

These shootings were the result of a barmy conspiracy theory that claimed high ranking US politicians were abusing children in a basement of a pizza restaurant (a pizza restaurant, incidentally, that had no basement). When Cliff was certificating the Disney film Lilo & Stitch (2008) he noticed a scene where Lilo hides in a tumble drier.

Cognisant of the tragic fact that a small number of children die each year after somehow getting in tumble driers, Cliff advised a small change. When the film was released on Disney+, instead of hiding in a tumble drier, Lilo hid under a table and used a pizza box to cover the gap between the table legs. Conspiracy theorists don't need a lot of evidence (or, often, any) to 'prove' their theory true and this was enough.

Why had this, of all scenes, been cut? And replaced with, of all things, a reference to pizza? It could only mean that Disney were sending out a message that they were part of a global paedophile ring. Luckily, the anger went no further than a few blowhards shouting on the Internet for a few days (this time) but it shows the dangerous tightrope a film examiner walks.

A Q&A touched on the time consuming classification of video games, how boring classifying pornography is (it's 25% of the job and who would watch hours of it each day in their right mind?), subliminal messaging, depictions of Muhammed in film, and the sex references (designed to go above children's heads and straight to adults) that are slipped in to Carry On films, pantomimes, and Mrs Doubtfire.

People asked about the support networks and therapy that are available to people whose job may involve watching hours upon hours of sex, violence, or sexualised violence and though Jim Cliff said this can be a problem his worst two days at work were, it seems, having to turn away from a scene in Jackass where the cast intentionally give themselves paper cuts and, worse still, spending three entire working days watching the Blu-Ray of Pixar's Cars and wishing, instead, that he was watching something horrible and depraved.

An evening with Jim Cliff was anything but horrible and depraved and it was far more edifying than six hours of either pornography or Teletubbies. His job managed to sound simultaneously fascinating and also incredibly monotonous. It sounds like a job you'd not want to do for too many years but, for an evening in March, still in lockdown, sat at home, it was great entertainment. He used the word 'fuck' a few times but it was non-aggressive and as the 'tone' of the evening was jovial, I'll give it a 12 rating.

No comments:

Post a Comment