Woah, steady on old boy (or old Beuys, okay that's that joke done twice now, I'll knock it on the head). What about music? What about friendship? What about telling stories? What about love? There are lots of ways of freeing, or trying to free, humankind from repression, even ALL the repressions.

Art definitely is one though. Creative endeavours are one of the things that lift us above most animals. Even things like the invention of refrigeration, darts, and the chip butty involve a level of creation that would be beyond a dog, cat, fox, or your average terrestrial mollusc but is Joseph Beuys, the fedora clad art theorist and pedagogue of North Rhine-Westphalia, the kind of artist who frees us?

Filzanzug (Felt Suit) (1970)

It's difficult to say if your only evidence is a visit to Beuys' Utopia at the Stag Monuments in Mayfair's Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac where, spread out over two floors and several rooms, you can find a selection of Beuys silkscreens, pencil drawings, aggregated sculptures, and assorted readymades dating from 1948 to 1986, the year of his death.

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac proudly announce, on the free pamphlet you can pick up at the desk on arrival, that this is "the most important UK exhibition of Beuys' work in over a decade" and that may well be the case but for somebody dipping a toe into the deep waters of his oeuvre it's all rather confusing. I felt like should've attended a crash course in Fluxus and 'happening' before I rocked up.

Of course there are things that even dilettantes such as myself will already know about Joseph Beuys. His installation has long been one of Tate Modern's most immediately eye catching, there's that time he spent three lots of eight hours in a cage with a coyote in a New York performance piece called I Like America and America Likes Me, and there's the story he liked to tell, possibly apocryphal, of when the Stuka dive bomber he was serving as rear-gunner in during World War II crash landed on the Crimean front in Ukraine and he was nursed back to health by Tatar tribesmen who covered his broken body in felt and animal felt. That's why the iconic suit is made of felt and why he uses fat in his art. It's a kind of thankyou to those that saved his life.

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac proudly announce, on the free pamphlet you can pick up at the desk on arrival, that this is "the most important UK exhibition of Beuys' work in over a decade" and that may well be the case but for somebody dipping a toe into the deep waters of his oeuvre it's all rather confusing. I felt like should've attended a crash course in Fluxus and 'happening' before I rocked up.

Of course there are things that even dilettantes such as myself will already know about Joseph Beuys. His installation has long been one of Tate Modern's most immediately eye catching, there's that time he spent three lots of eight hours in a cage with a coyote in a New York performance piece called I Like America and America Likes Me, and there's the story he liked to tell, possibly apocryphal, of when the Stuka dive bomber he was serving as rear-gunner in during World War II crash landed on the Crimean front in Ukraine and he was nursed back to health by Tatar tribesmen who covered his broken body in felt and animal felt. That's why the iconic suit is made of felt and why he uses fat in his art. It's a kind of thankyou to those that saved his life.

Kunst ist wenn man trotzdem lacht (Art is when you laugh despite everything) (1971)

Ecology and Socialism (1980)

But it's also a playful dig at conventions, a scrape on the surface of the art world's pretensions that Beuys only too happily replaces with further levels of pretension. Joseph Beuys wants his cake, or his animal fat, and he wants to eat it.

Utopia at the Stag Monuments is now the work that's actually wooing visitors to Tate Modern so this show is a collection, for the first time, of the 'original elements' that went in to it as well as 'pivotal works' that inspired it or were inspired by it. Beuys saw creativity as a 'universal principle that extended beyond traditional artistic activities into all areas of human production' so if you thought that bit about darts and chip butties was facetious it wasn't. There's some work goes into these blogs, you know! Not a lot - but some.

He felt art could transform society as keenly as he felt he could free us from repression but he felt this needed to be backed up by actions, lectures, and sustained political activism - all of which were, of course, absent from a rather upmarket Mayfair gallery. Is it okay to think a Beuys show would work better somewhere like the South London Gallery between Camberwell and Peckham where it's more likely to be visited by those in need of transformation and freedom from repression than in Mayfair?

Ohne Titel (Untitled) (1960)

Thor's Hammer (1961-62)

Although it's highly likely that those theoretical visitors, much like me, simply won't be steeped in enough Celtic mythology, German folkloric tradition, or primitive Christian symbolism to make head nor tail of what Beuys was trying to say or do.

Everyday, somewhat prosaic it has to be said, items stand in for animals. Hirsh (Stag) incorporates an ironing board, Ziege (Goat) a wheeled cart and pickaxe, and Schwane (Swans) is nothing more than some feint pencil and blue pastel marks on a translucent sheet of paper. Elsewhere materials such as blankets, metal clamps, dried grass, moss, tissue paper, a bed, and a 'wet battery' are employed to make bewildering, chin-strokingly so, points about the blurred lines between humanity and art.

Schlitten (Sled) (1969)

Hasenstein (Hare Stone) (1982)

Certainly lines are blurred but does it build a bridge between humanity and art? If it does it's a shaky rope bridge like in a Scooby Doo cartoon, a fun one to go over but not a particularly sturdy, or solid, construction. This show, and these works, are described elsewhere as 'a manifesto of hope for the future' but it's hard to really see them as meaning very much at all unless you've been given some kind of back story.

I can work out that the sled refers to a sled his Tatar rescuers towed him to safety on when he was serving in the Luftwaffe, I get that the felt suit serves as a kind of signifier, cypher, or signature even for Beuys himself, and I can just about see how the crudely carved crosses are intended to point an arrow in the direction of some kind of shared, and ancient, European history.

But I'm not a Christian (because it's bullshit) and I was never part of the Luftwaffe (not being German and being born more than twenty years after the end of World War II - and also because it's bullshit) so they don't really mean much to me. It seems to me a lot of Beuys' art is about one person and one person only - himself.

Evolutionaire Schwelle (Threshold of Evolution) (1985)

Feldbett (Campaign Bed) (1982)

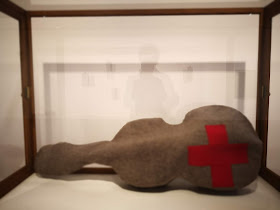

Infiltration-homogen fur cello (Infiltration-homogenous for Cello) (1966-85)

I doubt that's his intention but there's enough narcissism knocking around these days and I find myself longing for an art that is more giving, more sharing. The earth caked telephone and the felt covered cello are fun, riffing on the idea of the Duchampian readymade, but works like Kunst ist wenn man trotzdem lacht (Art is when you laugh despite everything) and Ecology and Socialism are just a bit dull really. It's like a school detention where they don't even set you a proper task. How long are you supposed to look at this stuff for when you don't have the foggiest notion what it means and it's not even aesthetically pleasing. Can I go home now?

Erdtelefon (Earth Telephone) (1968)

Kleines Kraftwerk (Small Power Station) (1984)

Tisch mit Aggregat (Table with Aggregate) (1958-85)

Hirsch (Stag) (1958/1982)

Boothia Felix (1958/1982)

Ziege (Goat) (1958/1982)

Urtiere (Primordial Animals) (1958/1982)

Gekreuzigter Christus (mit Sonne) Crucified Christ (with Sun) (1949)

Maybe I'm an imbecile who doesn't get one of the greatest artists of the last century, I never claimed to be an educated art blogger - just an art blogger, or maybe I'm not - but Beuys himself said art, presumably his art, could serve as "a genuinely human medium for revolutionary change in the sense of

completing the transformation from a sick world to a healthy one" and while that's a noble, and admirable, thing to try to do if I'm not even sure how many art pills I need to take and when I need to take them my world, in terms of the art of Joseph Beuys, remains a sick one rather than a healthy one.

Some things, admittedly, do look great when you're sick but, in the Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, unfortunately not enough for me, or society (quite clearly at the moment), to be transformed. Maybe I'll get it when I grow up.

1 Kreuz (1 Cross) (before 1953)

No comments:

Post a Comment