About a month back I wrote about attending my first LAAG (London Atheist Activist Group) meeting and how much I enjoyed the evening. Since then I'd been looking forward to Jon Stewart's talk Inside AA:Can a non-existent God cure alcoholism? I wasn't to be disappointed.

Jon was born in Sheffield in the late 60s, had a fairly normal childhood, and was intelligent enough to go to uni in Manchester where he met Louise Wener and formed the band Sleeper. They had 5 top 20 singles and 3 top 10 albums so they did pretty well. Jon recounts the apex of their career being supporting REM (then a serious contender for biggest band on the planet) at Milton Keynes Bowl. Eventually the band split. Jon drifted into session work playing on unsuccessful albums by Mel C & k d lang and ended up living in America. Throughout all this he'd been drinking. It was showbiz. Everyone was drinking. But, in retrospect, he was hitting it harder than most.

Finally reaching rock bottom he dragged himself (I assumed not literally) into Alcoholics Anonymous on his doctor's advice. He sobered up. They helped save his life for which he remains eternally grateful. He found a sponsor (someone to help you through the early stages of sobriety). He intentionally chose a guy he thought was 'sciencey' as he wasn't looking to be converted to Christianity, or worse, some sort of woolly Spiritualism. The science guy turned out be a fully signed up believer and, eventually, so did Jon.

He tried to rationalise his new found beliefs by saying to himself that the God he believed in was a god of nature. Little things, like buses turning up on time to take him to AA meetings, would cement these beliefs in his head. Eventually, however, he came to feel he was lying to himself and it ate away at him. Another visit to the doctor. This time the advice was - get out of AA for your health. Those two medical visits neatly bookending Jon's time in AA. He still doesn't drink but he doesn't need AA anymore - and he doesn't need religion either.

There are probably as many theories as I've had drinks as to what causes alcoholism but the one Jon briefly ran through was the theory of a no longer useful evolutionary advantage. Our ancestors needed to fend off rivals for berries and to make sure they ate the best ones. The best ones were the shiny colourful ones. The shiny colourful ones had some kind of alcohol in them. It wasn't a tasty Rioja or a double malt but it was booze, of a sort, nonetheless.

It's worth noting that current thinking sees alcoholism as a continuum. You're not either an alcoholic or you're not. Theres's a scale but at one end of that scale there are people with serious problems. It's always been thus. There's a few dipsomaniacs in the bible. Noah gets epically pissed after the flood although it could be argued that he'd done well to live to 950 anyway. Lot got so drunk he impregnated his own daughters. In Judges 9:13 even God himself is 'cheereth' by wine.

So with all these biblical boozebags bouncing about it's something of an irony that AA, without any doubt the most well known service for alcoholics, sprang out of an American Christian missionary organisation. The Oxford Group. Founded by Dr Frank Buchman, a Pennsylvanian Lutheran minister of Swiss descent. Like a lot of nascent religious organisations popping up in the new country they believed in a fair bit of mumbo-jumbo although most of their aims were honourable. They wanted to stop wars and they were against racism - which was quite radical at the time. The copybook was not so much blotted, as completely ruined, when they decided to announce their support for Adolf Hitler as a bulwark against communism which was the thing they really really didn't like. The AA, to their credit, cut their ties with the Oxford Group on this. So at least twelve steppers aren't required to be goose steppers.

Alcoholics Anonymous were formed on June 10, 1935. Why so specific a date? It's the day that co-founder Bill Wilson (or Bill W if you're with the programme) had his last drink. There's a huge thing, within AA, made of the back-story of its founders. Bob Smith, a surgeon from Vermont, had drank all the way through prohibition but the more colourful story belongs to Bill W who'd done the same.

Also from Vermont, and sixteen years younger than Bob, he became a stock speculator. A naturally shy man, alcohol put him at ease which I'm sure most us can recognise. By the age of 40 the drink had got the better of him and he wanted to stop. He met an old drinking buddy, Ebby Thacher, who'd become sober (though not for long) with the help of the Oxford Group. Bill went for treatment, claimed he had a 'hot flash' of spiritual conversion, and never drank again.

He did, however, spend most of the next five years tripping his nuts off on LSD and indulging in creepily predatory behaviour towards the growing AA's young clients. It's said that on his deathbed, in 1971 he screamed, cursed, and demanded booze. Which those around him, his AA friends, wouldn't allow him. There's a whole game of Scruples right there.

Jon didn't just relate these stories for background colour. They're, or at least some of them are, relevant now because the twelve step programme that the co-founders devised has not changed at all since 1935. It's hardly in keeping with modern medical thinking. Either with regards to mental or physical health.

That's not the only issue with AA. There's the whole God thing, of course. Which both deters atheists and agnostics from seeking treatment and asks people at their lowest ebb to submit themselves to a higher power. There's also the claim that AA is 100% successful. This is justified on the basis that anyone who returns to drinking has failed as a person. AA are not to blame for people's weaknesses. Alcoholics should just believe more, pray harder.

There are lots of pros. They genuinely do stop somewhere between 5% and 20% of those who sign up drinking (it's difficult to say exactly as there's no precise definition of how long you'd need to not drink for before you can be included in the statistics). There is a sense of community. You can make friends in the group who understand what you've been through and don't look down on you. A vital psychological component of recovering from any addiction.

There are alternatives to AA though and very few people know about them because AA has dominated the agenda for so long. That's who everyone mentions when joking about people who drink too much. There are atheist groups dedicated to recovering sobriety, Jon claimed CBT had been a great help to him, and there's also something called the Sinclair method where those seeking treatment receive a drug called Naltrexone which blocks the positive reinforcement effects of ethanol in the brain. Success for this is rated anywhere up to 80% with a few patients reporting being able to drink moderately afterwards with no problems. Again, statistics and definitions are hard to verify or even obtain in the first place. But surely this option should at least be more widely known.

Jon Stewart wasn't there to try to destroy AA, there are much fiercer critics out there, but to try to encourage them to modernise and work with other organisations to help people. He disagreed with many of their techniques but he tried, and succeeded, in not being disagreeable. As he said, they saved his life and they continue to save lives today so there was no sledgehammer required to crack this nut.

He ended on a positive note and suggested that many health organisations were coming round to progressive methods and more secular sobriety groups were being formed. It was an absolutely fascinating talk and I'd recommend, if you get a chance, you get along to see it. I think it really helped some people there. There were other alcoholics, ex-alcoholics, recovering alcoholics (shall we just say people) there who movingly and bravely shared testimonies of their experiences. At one point it was getting like Alcoholics Anonymous Anonymous.

As Jon was packing his laptop up I accidentally caught his gaze. Perhaps I read too much into it but it seemed to me he smiled the smile of a contented man, a man who knew his self and was happy with who that self was, a man who'd visited some very dark places and didn't want to go back. Later I thought of his friends and family who, surely, on occasions, wondered if he'd drink himself to death. I thought how that smile must light up their hearts and I thought it was worth listening to this man - and it's worth living.

Thursday, March 10, 2016

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

A polydactyl cat walks into a bar

Eleven times a year on the first Monday of the month in a pub in Camden (The Monarch, near Chalk Farm) an assorted group of scientists, cynics, non-believers, believers, and the plain curious meet to hear a talk about subjects that include anything from creationist schools to drug taking in sport, artificial intelligence, the science of taste, ghost hunting, the Alpha course, anti-vaccination and the urban myths behind London's parakeet population.

The talk lasts about three quarters of an hour. There's a break for about fifteen minutes into which you're encouraged to lob £3 in to a pint pot to cover expenses, and then there's usually a Q&A session with the speaker. It's an amicable evening all round. People occasionally disagree but I've never witnessed anyone get heated. It's a decent pub with friendly bar staff and a good range of ales and food. Although some nights it's hard to get a seat. Testament to the growing popularity of the event.

Further evidence of the same can be found in the fact that these evenings have spread out from London into Dundee, Aberystwyth, Lewes and Tunbridge Wells. Even overseas with events springing up in places like Brussels, Paris and Leipzig.

I started going over a decade ago on the recommendation of my friend and colleague Richard Sanderson who now runs the well worth investigating Linear Obsessional record label. It was a more shambolic affair those days and many of the speakers who were invited to its then London Bridge HQ were believers in the paranormal or some such who were summarily debunked.

That was fun for a while but I guess the organisers got fed up of stealing candy from babies or decided that it'd be far more edifying to learn something on a night out rather than get into slanging matches with flat Earthers etc;

Other things happened in my life and I pretty much forgot all about Skeptics in the Pub. A few years back I got to thinking about them and wondered if they were still going on. Obviously I found out they were so I popped along to see what'd changed. I was glad I did. I now try and get along to every event if possible and have even branched out into visiting the Greenwich and Soho branches. We have to have more of everything in London. We're greedy.

It's rare I join in the Q&A, I'm mostly content to simply listen and learn, but I always come away feeling energised. If I've had a shitty, or just a mind-numbing, day at work I find a couple of hours in such company really blows the old cobwebs off. There's been so many good evenings, and very few disappointing ones, I wish I'd started blogging earlier so I could've bent your metaphorical ears about them sooner.

Monday gone's was an excellent example of everything that's so right about the format. Dr Kat Arney is a science communicator and award winning blogger (there are awards for this!?) for Cancer Research. She's just written a book about how our genes work called Herding Hemingway's Cats.

Being virtually illiterate scientifically I was wary of going. I thought I might not have the faintest clue what she, or anyone else, was talking about. It happens to me sometimes. Quite often if truth be told.

I needn't have worried. She's taken the pop science route with both her book and the talk. It's a method that works. After a brief explanation of what genes are, to the level that anyone knows, and how DNA works she got into the good stuff. You need to buy her book if you want 'the science bit' but a couple of anecdotes that interested and, in the latter case, amused me were about sticklebacks and the human penis.

Sticklebacks have elaborate breeding behaviour. Though they live in sea water they'll only breed in fresh water. Not cheap dates it appears. Something like 10,000 years ago a load of sticklebacks were all busy enjoying their annual fishy fuckfest when they got so carried away they didn't notice they couldn't get back to the sea afterwards. So they stayed put and slowly, but not by evolutionary standards, became a different species. The sea water sticklebacks have little spikes protruding from their undercarriages. The freshwater ones don't. One little DNA switch didn't go off one day and from there a whole new species evolved.

It's the same with willies. Yes, actual men's cocks. Our primate ancestors all have spiky members as do many other animals as anyone who's heard foxes rutting away beneath the silvery moon will testify. One day a child was born with a smooth dick. That child grew up to have, hardly surprisingly, an evolutionary advantage. Now we've all got them, well 50% of us, and, quite frankly, no-one wants to go back to spikes. It's the very definition of a win-win.

It wasn't all fun, but interesting, stories. There were ethical questions raised about eugenics and that hoary old chestnut nature versus nurture (both, btw) but for those I'd recommend you buy the book. It's got some lovely stuff on Ernest Hemingway's polydactyl cats that now roam huge swathes of America's Eastern seaboard.

For further enlilghtenment I'd recommend you get along to a future Skeptics event. The next one is about the ins and outs of being in or out of Europe. It's one I really ought to attend as, once again, I'm pretty baffled by it all.

The talk lasts about three quarters of an hour. There's a break for about fifteen minutes into which you're encouraged to lob £3 in to a pint pot to cover expenses, and then there's usually a Q&A session with the speaker. It's an amicable evening all round. People occasionally disagree but I've never witnessed anyone get heated. It's a decent pub with friendly bar staff and a good range of ales and food. Although some nights it's hard to get a seat. Testament to the growing popularity of the event.

Further evidence of the same can be found in the fact that these evenings have spread out from London into Dundee, Aberystwyth, Lewes and Tunbridge Wells. Even overseas with events springing up in places like Brussels, Paris and Leipzig.

I started going over a decade ago on the recommendation of my friend and colleague Richard Sanderson who now runs the well worth investigating Linear Obsessional record label. It was a more shambolic affair those days and many of the speakers who were invited to its then London Bridge HQ were believers in the paranormal or some such who were summarily debunked.

That was fun for a while but I guess the organisers got fed up of stealing candy from babies or decided that it'd be far more edifying to learn something on a night out rather than get into slanging matches with flat Earthers etc;

Other things happened in my life and I pretty much forgot all about Skeptics in the Pub. A few years back I got to thinking about them and wondered if they were still going on. Obviously I found out they were so I popped along to see what'd changed. I was glad I did. I now try and get along to every event if possible and have even branched out into visiting the Greenwich and Soho branches. We have to have more of everything in London. We're greedy.

It's rare I join in the Q&A, I'm mostly content to simply listen and learn, but I always come away feeling energised. If I've had a shitty, or just a mind-numbing, day at work I find a couple of hours in such company really blows the old cobwebs off. There's been so many good evenings, and very few disappointing ones, I wish I'd started blogging earlier so I could've bent your metaphorical ears about them sooner.

Monday gone's was an excellent example of everything that's so right about the format. Dr Kat Arney is a science communicator and award winning blogger (there are awards for this!?) for Cancer Research. She's just written a book about how our genes work called Herding Hemingway's Cats.

Being virtually illiterate scientifically I was wary of going. I thought I might not have the faintest clue what she, or anyone else, was talking about. It happens to me sometimes. Quite often if truth be told.

I needn't have worried. She's taken the pop science route with both her book and the talk. It's a method that works. After a brief explanation of what genes are, to the level that anyone knows, and how DNA works she got into the good stuff. You need to buy her book if you want 'the science bit' but a couple of anecdotes that interested and, in the latter case, amused me were about sticklebacks and the human penis.

Sticklebacks have elaborate breeding behaviour. Though they live in sea water they'll only breed in fresh water. Not cheap dates it appears. Something like 10,000 years ago a load of sticklebacks were all busy enjoying their annual fishy fuckfest when they got so carried away they didn't notice they couldn't get back to the sea afterwards. So they stayed put and slowly, but not by evolutionary standards, became a different species. The sea water sticklebacks have little spikes protruding from their undercarriages. The freshwater ones don't. One little DNA switch didn't go off one day and from there a whole new species evolved.

It wasn't all fun, but interesting, stories. There were ethical questions raised about eugenics and that hoary old chestnut nature versus nurture (both, btw) but for those I'd recommend you buy the book. It's got some lovely stuff on Ernest Hemingway's polydactyl cats that now roam huge swathes of America's Eastern seaboard.

For further enlilghtenment I'd recommend you get along to a future Skeptics event. The next one is about the ins and outs of being in or out of Europe. It's one I really ought to attend as, once again, I'm pretty baffled by it all.

Monday, March 7, 2016

'86 in '16

If The June Brides really were looking forward to getting married in the flaming month it'd probably end up pissing down on their wedding day. They haven't enjoyed the best of luck in their on-off career. Not signing to the fledgling Creation label because it would've been too obvious and turning down an appearance on the influential (to a certain demographic) C86 cassette given away free with the NME thirty years ago.

It's a pity because they deserved more. Having Oxford Street's 100 Club three quarters full 31 years after their only album came out, and that was a mini one, is fairly impressive. Lots of bands from the same time would struggle and some of their posters are on the stairs as you descend into the basement for an evening of pints in plastic glasses, bogs with no locks on the doors, and men (and they are mostly men) of a certain age.

But for an act that managed to bridge the Postcard sound of Orange Juice and The Go-Betweens with later jangly bands like The Bodines and Mighty Mighty whilst marrying a nascent chamber pop element to the songwriting chops of a Roddy Frame or David Gedge it seems like a dollar short and a day late.

The youngest people in the room by some margin are Brighton quartet Clipper. Looks wise they're ticking some fairly standard indie boxes. The drummer, who according to their Facebook page calls himself The Edge and can look forward to a catch up with U2's lawyers if they ever get famous, sports a textbook stripey t-shirt. Sensible shoes and checked shirts abound and singer Noah Bisseker sports the sort of curtain hairstyle not seen since Ian Walker was between the sticks for Tottenham. The songs are punchy enough and there's enough going on to suggest that with time and confidence they can move away from supporting blokes the age of their dads.

The Wolfhounds may look like a pub darts team but there's no fat on the old tunes whatsoever. They've been back together for over a decade now so it'd be understandable, if less forgivable, if interest had waned. The go-faster stripe on Dave Callahan's guitar seems to act as a reminder to him to never let the pace slip. Which they don't. Anti-Midas Touch, the nearest thing they had to a hit and, alas, something Callahan seems to be suffering technically, even sees an outbreak of dancing. Well, two men. Lots of head nodding though. Both in confirmation and enjoyment. They are rather good.

While we're not being entirely complimentary about what bands look like The June Brides consist of Roger Lloyd-Pack in an ITV drama about a man living on a canal boat, a nervous geography teacher, Kevin Rowland in the clothes he uses to take the bins out, and a retired East End gangster who'd rather be floating on a lilo sipping a pina colada in the Costa del Sol.

None of which provides any clue as to how they sound. Which, initially, is not good. Problems with both the viola and the trumpet mean the whole aforementioned chamber music thing doesn't really come through during the first couple of songs including the excellent The Instrumental. It's fixed pretty speedily but it takes the band a few minutes to get their mojo back. Phil Wilson's sweet voice and pensive lyrics are a strange fit but a beguiling one. Every Conversation sees a singalong. This Town puts a worm in the ear that's still there two days later. In The Rain is the rediscovered gem of the night and Heard You Whisper and Sick, Tired And Drunk bring memories of years spent in teenage bedrooms flooding back. Which is a good thing. Occasionally.

It was more low-key triumph than resounding success but that was always on the cards and it'd seem a little harsh to suggest a gig by two bands from the so-called shambling scene was a bit shambolic even if it was. A fun evening. Thanks to Darren and Cheryl for joining me.

It's a pity because they deserved more. Having Oxford Street's 100 Club three quarters full 31 years after their only album came out, and that was a mini one, is fairly impressive. Lots of bands from the same time would struggle and some of their posters are on the stairs as you descend into the basement for an evening of pints in plastic glasses, bogs with no locks on the doors, and men (and they are mostly men) of a certain age.

But for an act that managed to bridge the Postcard sound of Orange Juice and The Go-Betweens with later jangly bands like The Bodines and Mighty Mighty whilst marrying a nascent chamber pop element to the songwriting chops of a Roddy Frame or David Gedge it seems like a dollar short and a day late.

The youngest people in the room by some margin are Brighton quartet Clipper. Looks wise they're ticking some fairly standard indie boxes. The drummer, who according to their Facebook page calls himself The Edge and can look forward to a catch up with U2's lawyers if they ever get famous, sports a textbook stripey t-shirt. Sensible shoes and checked shirts abound and singer Noah Bisseker sports the sort of curtain hairstyle not seen since Ian Walker was between the sticks for Tottenham. The songs are punchy enough and there's enough going on to suggest that with time and confidence they can move away from supporting blokes the age of their dads.

The Wolfhounds may look like a pub darts team but there's no fat on the old tunes whatsoever. They've been back together for over a decade now so it'd be understandable, if less forgivable, if interest had waned. The go-faster stripe on Dave Callahan's guitar seems to act as a reminder to him to never let the pace slip. Which they don't. Anti-Midas Touch, the nearest thing they had to a hit and, alas, something Callahan seems to be suffering technically, even sees an outbreak of dancing. Well, two men. Lots of head nodding though. Both in confirmation and enjoyment. They are rather good.

While we're not being entirely complimentary about what bands look like The June Brides consist of Roger Lloyd-Pack in an ITV drama about a man living on a canal boat, a nervous geography teacher, Kevin Rowland in the clothes he uses to take the bins out, and a retired East End gangster who'd rather be floating on a lilo sipping a pina colada in the Costa del Sol.

None of which provides any clue as to how they sound. Which, initially, is not good. Problems with both the viola and the trumpet mean the whole aforementioned chamber music thing doesn't really come through during the first couple of songs including the excellent The Instrumental. It's fixed pretty speedily but it takes the band a few minutes to get their mojo back. Phil Wilson's sweet voice and pensive lyrics are a strange fit but a beguiling one. Every Conversation sees a singalong. This Town puts a worm in the ear that's still there two days later. In The Rain is the rediscovered gem of the night and Heard You Whisper and Sick, Tired And Drunk bring memories of years spent in teenage bedrooms flooding back. Which is a good thing. Occasionally.

It was more low-key triumph than resounding success but that was always on the cards and it'd seem a little harsh to suggest a gig by two bands from the so-called shambling scene was a bit shambolic even if it was. A fun evening. Thanks to Darren and Cheryl for joining me.

Sunday, March 6, 2016

Auerbach:A page torn from the book of life

Tate Britain's ambitiously priced Frank Auerbach exhibition doesn't contain much to read. Which is tricky for bloggers hoping to crib notes but great for those of you who want to view the work of this much loved, and much maligned, artist on its own merits.

Six rooms have been laid out by the octogenarian himself and a final one by the curator (and occasional sitter for Auerbach) Catherine Lampert. The first is given over to what, to these eyes, looks like classic Frank. Oily paint so thickly applied it'll look like a mess to some. Building Site, Earls Court Road, Winter from 1953, below, looks dirty, sooty, a volcanic aftermath, but its interest lies in its flirtation with abstraction. A relationship never quite consummated.

Some of the EOW heads (EOW being Estella West, Auerbach's first wife and former actor for Peter Ustinov) use a less muddier palate which lifts the gloom in the room and adds contrast. It's not like gloom's a bad thing per se but it shows a side to the artist I'd hitherto been unaware of.

EOW crops up again in the second room. The paint worked up and piled on to a frankly terrifying degree. It recalls Munch or Van Gogh if they'd, remarkably, gone a couple of steps further. Or, a cynic might say, the daubs of a chancer. The most aesthetically pleasing works here are his landscapes, if we're being liberal with the term, of Primrose Hill and his old favourite Mornington Crescent.

The above work from '67 is only barely recognisable as an actual place but the bold use of yellows, greens, and reds create depth and a sense of the hustle and bustle in south Camden's urban milieu.

In the 70s his paintings appear to have poured straight on to the canvas with no sense of composition whatsoever. But our Frank was no Jackson Pollock. Like Dolly Parton spending a million dollars to look that 'cheap' or Stewart Lee beavering away on a routine which gives the impression he's lost the plot it's an illusion of sorts. Auerbach toiled in his studio from morning to night every day endlessly working and reworking so every jerky diagonal line, every smudged mark, and each squeezy blob of paint is just how he intended it to be. Your five year old could've done it but, let's face it, they'd have got bored pretty quickly and gone off to play with Lego Transformers.

His portraits of the 80s were close, thematically, to Francis Bacon's work. Twisted, ghastly, ghostly fizzogs gawp back at us with a fierce intensity. Despite this and unlike, perhaps, Leon Kossoff's work it's hard to read much into them. Which is, possibly, a downside to this meticulous technique. A danger of overworking and removing some of the core emotional heft. That's a harsh, even a little unfair, criticism as, clearly, he strives hard for that not to happen and succeeds more often than not.

The 90s saw a blast of colour. Still the reclining heads, like so many sphinxes, refused to reveal their secrets. One of JYM (Julia, another of Auerbach's reguar sitters who would visit his studio for a scheduled appointment on a weekly basis) makes her look like a little monkey. Simian similarities aside his admiration of women was, as rumour had it, enthusiastically pursued. His keenest love, though, seemed to be for the tower blocks of Mornington Crescent, now rendered marginally more realistically. If still equally effectively and startlingly. You can almost hear the beep of horns and smell the kebabs in his 1997 take on his part of town.

I'd thought of Auerbach as primarily a left-field portraitist so it was good to see there was more breadth to his work. This event also taught me that he'd made better use of colour than I'd imagined. Sometimes there's even a suggestion of the fauvist influence of Derain or Matisse. Others like Next Door III, below, from this decade, hint at Cezanne's proto-cubist visions of Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Graphite works, charcoal pieces, and etchings flesh out the retrospective and these are interesting in gaining an understanding of his technique. As is the film showing in the shop. But it's for the oil paintings you should come. It's unlikely this exhibition will win him any new fans but existing admirers won't be alienated and will leave happier though lighter of wallet. If still unsure just what it is that makes this most enigmatic, yet engaging, of artists tick. It's art for art's sake - and there's nothing wrong with that.

Six rooms have been laid out by the octogenarian himself and a final one by the curator (and occasional sitter for Auerbach) Catherine Lampert. The first is given over to what, to these eyes, looks like classic Frank. Oily paint so thickly applied it'll look like a mess to some. Building Site, Earls Court Road, Winter from 1953, below, looks dirty, sooty, a volcanic aftermath, but its interest lies in its flirtation with abstraction. A relationship never quite consummated.

Some of the EOW heads (EOW being Estella West, Auerbach's first wife and former actor for Peter Ustinov) use a less muddier palate which lifts the gloom in the room and adds contrast. It's not like gloom's a bad thing per se but it shows a side to the artist I'd hitherto been unaware of.

EOW crops up again in the second room. The paint worked up and piled on to a frankly terrifying degree. It recalls Munch or Van Gogh if they'd, remarkably, gone a couple of steps further. Or, a cynic might say, the daubs of a chancer. The most aesthetically pleasing works here are his landscapes, if we're being liberal with the term, of Primrose Hill and his old favourite Mornington Crescent.

The above work from '67 is only barely recognisable as an actual place but the bold use of yellows, greens, and reds create depth and a sense of the hustle and bustle in south Camden's urban milieu.

In the 70s his paintings appear to have poured straight on to the canvas with no sense of composition whatsoever. But our Frank was no Jackson Pollock. Like Dolly Parton spending a million dollars to look that 'cheap' or Stewart Lee beavering away on a routine which gives the impression he's lost the plot it's an illusion of sorts. Auerbach toiled in his studio from morning to night every day endlessly working and reworking so every jerky diagonal line, every smudged mark, and each squeezy blob of paint is just how he intended it to be. Your five year old could've done it but, let's face it, they'd have got bored pretty quickly and gone off to play with Lego Transformers.

His portraits of the 80s were close, thematically, to Francis Bacon's work. Twisted, ghastly, ghostly fizzogs gawp back at us with a fierce intensity. Despite this and unlike, perhaps, Leon Kossoff's work it's hard to read much into them. Which is, possibly, a downside to this meticulous technique. A danger of overworking and removing some of the core emotional heft. That's a harsh, even a little unfair, criticism as, clearly, he strives hard for that not to happen and succeeds more often than not.

The 90s saw a blast of colour. Still the reclining heads, like so many sphinxes, refused to reveal their secrets. One of JYM (Julia, another of Auerbach's reguar sitters who would visit his studio for a scheduled appointment on a weekly basis) makes her look like a little monkey. Simian similarities aside his admiration of women was, as rumour had it, enthusiastically pursued. His keenest love, though, seemed to be for the tower blocks of Mornington Crescent, now rendered marginally more realistically. If still equally effectively and startlingly. You can almost hear the beep of horns and smell the kebabs in his 1997 take on his part of town.

I'd thought of Auerbach as primarily a left-field portraitist so it was good to see there was more breadth to his work. This event also taught me that he'd made better use of colour than I'd imagined. Sometimes there's even a suggestion of the fauvist influence of Derain or Matisse. Others like Next Door III, below, from this decade, hint at Cezanne's proto-cubist visions of Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Graphite works, charcoal pieces, and etchings flesh out the retrospective and these are interesting in gaining an understanding of his technique. As is the film showing in the shop. But it's for the oil paintings you should come. It's unlikely this exhibition will win him any new fans but existing admirers won't be alienated and will leave happier though lighter of wallet. If still unsure just what it is that makes this most enigmatic, yet engaging, of artists tick. It's art for art's sake - and there's nothing wrong with that.

Friday, March 4, 2016

Grave decoration

If you're the sort of person who perceives the adjective 'flowery' in the pejorative then the Royal Academy's new show Painting the Modern Garden:Monet to Matisse may not be the one for you. Entering the first room is like being part of Diana's cortege as pelargoniums, lilacs, and other assorted Morrissey back pocket accessories immediately assault your vision.

The RA are attempting to tell the story of art, or even life itself, from the 1860s to the 1920s through the prism of botanical paintings and they've assembled a cast of some of the biggest names of the era's art world to do it. Starting with the Impressionists seems reasonable enough. Often the view taken is that a retreat into the wilderness of the garden was a refuge from the industrialisation of the time. Though it could also be said that some artists' new found wealth enabled them to live in bigger properties with larger gardens and enjoy more free time in them.

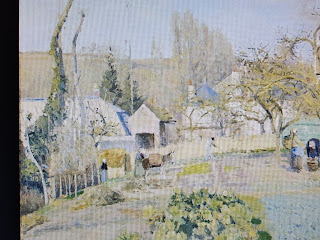

There are works in the first rooms from Cezanne, Manet, Bazille (who leaves our story early having died in 1870 in the Franco-Prussian war). My favourite is a piece by Camille Pissarro, a man who sported an even longer beard than Monet, called Kitchen Gardens at L'Hermitage from 1874. It's very yellow and that shines out amongst the greenery surrounding it.

Gustave Caillebotte was an artist I'd previously known very little about but as we move deeper into the circle it's his paintings that make the biggest impact. His Nasturtiums (1892) appears almost abstract from the right distance.

Caillebotte also stepped away from pure flower painting to depict workaday vegetable gardens, rendering walls as beautiful as the greenery. You can also witness Berthe Morisot's looser brush strokes pointing the way for later developments.

By the 1880s gardens, and their depictions, were getting more tropical. Monet's particularly. Not least because they were painted in the Italian seaside village of Bordighera. This paves the way, the curators hint, for garden painting to leave France and go international. John Singer Sargent's rather stuffy works pale next to those of Joaquin Sorolla (who had a very cushy job travelling around the gardens of his native Spain). You may wish to avoid his portrait of Tiffany, the jeweller, in his whites though. Unless you possess either a pair of shades or a strong stomach. It's a bit icky.

Childe Hassam shows up from across the Atlantic, painting poppies in Maine. Max Liebermann's ur-Auerbach oily splodges compete with his Nordic looking trees in his Wannsee gardens works. They're pretty good if a little surprising in the context they're presented in. Johan Krouthen's family portrait from Linkoping brings both Sweden and a sense of narrative into the genre. There's two sets of chrysanthemums and Dennis Miller Bunker's seem very different to Tissot's. It could be down to the latter employing the inclusion of a very Victorian lady and the former showing an empty path. Something that crops up often in this exhibition.

Scattered amongst the paintings there are books about dahlias, pictures of the stars painting plein air, seats for the expected older patrons to relax, and a room on how to make your own garden. This contains catalogues of aquatic plants, nursery delivery slips, photos of Monet in his big hat from a 1933 issue of Country Life, and, best of all, some exquisitely beautiful Hiroshige and Hokusai woodblocks. Japan, at the time of the show, having only recently opened up trade with the West. It's easier to see how these influenced garden design than the art itself . Not least in Monet's Giverny (his Japanese footbridge from 1899 below) which has an entire room devoted to it.

His water lilies too of course. Pink ones. Green ones. Dreamy ones. Serene ones. Years and years worth. As we know the effect of light on the given subject was one of Monet's great gifts to the art world. After all that his peonies look almost brutal. Which set you up for the Gardens of Silence.

Joaquin Mir Y Trinxet's The Artist's Garden from 1922 hints at an aura of mystery and is contrasted well with Santiago Rusinol's Spanish palaces. Rusinol's use of colour lights up the room which has been, oddly, if effectively, darkened. It's a score draw between Spain and Catalonia here.

Not all the curator's party pieces come off so well. The avant-garden pun was one they clearly couldn't resist. The room's good though. Dufy's tropical tones play off against Nolde's fauvist smudges. August Mache's menacing garden path echoes those of Bunker earlier. Matisse brings a sense of naivety to the party, Van Gogh turbo-charges Impressionism, and Munch's childlike, yet frantic, expressionism is a delight. There's even a Klimt. Klee, as ever, has something of the East about him. Klee loved to paint plants and made about 10,000 works in the discipline. Roughly 10% of his entire output.

The Nabis, Bonnard, and Denis seem like they've stepped back in revulsion from the flowering of the avant-garde(n?) and, in retrospect, appear too safe and cosy. Vuillard is an honourable exception but at the end you're thrown straight back into the revolution happening in art. Which is where this show is at its best. When it follows a narrative it works well. When it deviates it's trickier. Luckily the script is stuck to more often than not.

The final rooms are devoted to Monet and Monet alone. Many water lilies and some rather dark canvases. Compare his Japanese Bridge of 1923, below, to the one from only 25 years before and you'll wonder if contemporary critics thought he'd gone senile.

Perhaps he had. He was certainly very old and had become deeply affected with World War I raging across Europe. The memorials for which would find flowers reverting back to one of their more traditional uses.

Thanks to Kathy Smith for enabling this cultural outing.

The RA are attempting to tell the story of art, or even life itself, from the 1860s to the 1920s through the prism of botanical paintings and they've assembled a cast of some of the biggest names of the era's art world to do it. Starting with the Impressionists seems reasonable enough. Often the view taken is that a retreat into the wilderness of the garden was a refuge from the industrialisation of the time. Though it could also be said that some artists' new found wealth enabled them to live in bigger properties with larger gardens and enjoy more free time in them.

There are works in the first rooms from Cezanne, Manet, Bazille (who leaves our story early having died in 1870 in the Franco-Prussian war). My favourite is a piece by Camille Pissarro, a man who sported an even longer beard than Monet, called Kitchen Gardens at L'Hermitage from 1874. It's very yellow and that shines out amongst the greenery surrounding it.

Gustave Caillebotte was an artist I'd previously known very little about but as we move deeper into the circle it's his paintings that make the biggest impact. His Nasturtiums (1892) appears almost abstract from the right distance.

Caillebotte also stepped away from pure flower painting to depict workaday vegetable gardens, rendering walls as beautiful as the greenery. You can also witness Berthe Morisot's looser brush strokes pointing the way for later developments.

By the 1880s gardens, and their depictions, were getting more tropical. Monet's particularly. Not least because they were painted in the Italian seaside village of Bordighera. This paves the way, the curators hint, for garden painting to leave France and go international. John Singer Sargent's rather stuffy works pale next to those of Joaquin Sorolla (who had a very cushy job travelling around the gardens of his native Spain). You may wish to avoid his portrait of Tiffany, the jeweller, in his whites though. Unless you possess either a pair of shades or a strong stomach. It's a bit icky.

Childe Hassam shows up from across the Atlantic, painting poppies in Maine. Max Liebermann's ur-Auerbach oily splodges compete with his Nordic looking trees in his Wannsee gardens works. They're pretty good if a little surprising in the context they're presented in. Johan Krouthen's family portrait from Linkoping brings both Sweden and a sense of narrative into the genre. There's two sets of chrysanthemums and Dennis Miller Bunker's seem very different to Tissot's. It could be down to the latter employing the inclusion of a very Victorian lady and the former showing an empty path. Something that crops up often in this exhibition.

Scattered amongst the paintings there are books about dahlias, pictures of the stars painting plein air, seats for the expected older patrons to relax, and a room on how to make your own garden. This contains catalogues of aquatic plants, nursery delivery slips, photos of Monet in his big hat from a 1933 issue of Country Life, and, best of all, some exquisitely beautiful Hiroshige and Hokusai woodblocks. Japan, at the time of the show, having only recently opened up trade with the West. It's easier to see how these influenced garden design than the art itself . Not least in Monet's Giverny (his Japanese footbridge from 1899 below) which has an entire room devoted to it.

His water lilies too of course. Pink ones. Green ones. Dreamy ones. Serene ones. Years and years worth. As we know the effect of light on the given subject was one of Monet's great gifts to the art world. After all that his peonies look almost brutal. Which set you up for the Gardens of Silence.

Joaquin Mir Y Trinxet's The Artist's Garden from 1922 hints at an aura of mystery and is contrasted well with Santiago Rusinol's Spanish palaces. Rusinol's use of colour lights up the room which has been, oddly, if effectively, darkened. It's a score draw between Spain and Catalonia here.

Not all the curator's party pieces come off so well. The avant-garden pun was one they clearly couldn't resist. The room's good though. Dufy's tropical tones play off against Nolde's fauvist smudges. August Mache's menacing garden path echoes those of Bunker earlier. Matisse brings a sense of naivety to the party, Van Gogh turbo-charges Impressionism, and Munch's childlike, yet frantic, expressionism is a delight. There's even a Klimt. Klee, as ever, has something of the East about him. Klee loved to paint plants and made about 10,000 works in the discipline. Roughly 10% of his entire output.

The Nabis, Bonnard, and Denis seem like they've stepped back in revulsion from the flowering of the avant-garde(n?) and, in retrospect, appear too safe and cosy. Vuillard is an honourable exception but at the end you're thrown straight back into the revolution happening in art. Which is where this show is at its best. When it follows a narrative it works well. When it deviates it's trickier. Luckily the script is stuck to more often than not.

The final rooms are devoted to Monet and Monet alone. Many water lilies and some rather dark canvases. Compare his Japanese Bridge of 1923, below, to the one from only 25 years before and you'll wonder if contemporary critics thought he'd gone senile.

Perhaps he had. He was certainly very old and had become deeply affected with World War I raging across Europe. The memorials for which would find flowers reverting back to one of their more traditional uses.

Thanks to Kathy Smith for enabling this cultural outing.

Sunday, February 21, 2016

Late developments

The V&A's free exhibition of Julia Margaret Cameron's ground-breaking, slightly out of focus, scratched, and even smudged photographs celebrates the bicentenary of her birth in Calcutta as well as marking 150 years since her first public show at the same venue. Then known as the South Kensington Museum.

Fifty may seem relatively old to be hosting your first show but she'd only taken up photography seriously two years earlier when she'd been presented with a camera as a present by her daughter. By then she'd been educated in France, moved back to India, married Charles Hay Cameron (twenty years her senior and a member of the Law Commission), then to London, before finally settling in the Isle of Wight in a home they named Dimbola Lodge. So, in fact, her progress was actually pretty rapid.

Her first subjects, like most snappers, were family and friends. But she experimented with dramatic lighting and close up composition thus forging what was to become a signature style. A portrait of her grandson, Archie, in the guise of the Christ child foretold her habit of placing her subjects in biblical and allegorical settings.

Another of Alfred Tennyson, her Isle of Wight neighbour and friend, positioned her neatly in the nascent field of celebrity portrait. This area of her work also took in images of playwright Robert Browning, violinist Joseph Joachim, the astronomer Herschel, and, perhaps most notably Charles Darwin. There was even one of Prince Dejazmatch Alemayehu, the son of the Ethiopian emperor.

Society figures too like Lord and Lady Elcho. Lady Adelaide Talbot as Melancholy (from the Milton poem Il Penseroso) could almost pass as a still frame from a Carl Theodor Dreyer film.

Unperturbed by conservative observers who suggested that photography should only be used to document truthful subject matter she pushed forward with interpretations of works by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Guido Reni proving photography could operate equally both as art form and reportage.

Inspiration too came from Homer, Keats and Coleridge. Even the sentimental genre paintings of the time. Whilst one eye looked back another was focused on the horizon. She gently pushed at prevalent gender stereotyping. Her women posed in what was then seen as traditionally male fashion, men appeared as historical female figures, and an 1865 shot showed Cameron's maid, Mary Hillier, not for the last time, as Sappho.

Despite the taboo testing her devout Christianity was often to the fore. Not least in a series of Madonna groups featuring, again, Mary Hillier. That maid earned her keep. Mangers, crosses, drapery, flowers, and other signifiers of the holy life were all employed to emphasise the virtuous nature of her beliefs. To modern eyes these are among her weaker works, moralising and twee with a hint of the dreaded chocolate box, but it's worth a deeper look. Incremental technological innovations had come into play whilst darkness, and even some good old fashioned Old Testament death, lurked in the murky margins.

In 1874 Tennyson invited Cameron, and she accepted, to provide illustrations to his Idylls of the King. There's a kind of Moondog vibe to the above piece and it bears witness to her increasing confidence. As did her brave use of soft focus, multiple negatives and combination prints.

Though not to the liking of many critics at the time she had still become both a successful and a commercial artist unashamed, and unabashed, in using her connections to increase her capital. The fact her high society chums were able to sign the portraits before sale didn't hurt none either.

Then, at the height of her fame in 1875, the family moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) where, due to a whole host of logistical problems, her artistic career ended as abruptly as it had began. She'd had barely more than a decade of notoriety and four years later she passed away at the age of 63.

This exhibition does a good job of shedding some light on a photographic pioneer who was certainly not well known to this writer prior to his attendance. It could, perhaps, have compared and contrasted her against contemporaries and gave a better understanding of the time and milieu in which she worked. Then again that could be another show for another day - and probably not a free one either.

Fifty may seem relatively old to be hosting your first show but she'd only taken up photography seriously two years earlier when she'd been presented with a camera as a present by her daughter. By then she'd been educated in France, moved back to India, married Charles Hay Cameron (twenty years her senior and a member of the Law Commission), then to London, before finally settling in the Isle of Wight in a home they named Dimbola Lodge. So, in fact, her progress was actually pretty rapid.

Her first subjects, like most snappers, were family and friends. But she experimented with dramatic lighting and close up composition thus forging what was to become a signature style. A portrait of her grandson, Archie, in the guise of the Christ child foretold her habit of placing her subjects in biblical and allegorical settings.

Another of Alfred Tennyson, her Isle of Wight neighbour and friend, positioned her neatly in the nascent field of celebrity portrait. This area of her work also took in images of playwright Robert Browning, violinist Joseph Joachim, the astronomer Herschel, and, perhaps most notably Charles Darwin. There was even one of Prince Dejazmatch Alemayehu, the son of the Ethiopian emperor.

Society figures too like Lord and Lady Elcho. Lady Adelaide Talbot as Melancholy (from the Milton poem Il Penseroso) could almost pass as a still frame from a Carl Theodor Dreyer film.

Unperturbed by conservative observers who suggested that photography should only be used to document truthful subject matter she pushed forward with interpretations of works by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Guido Reni proving photography could operate equally both as art form and reportage.

Inspiration too came from Homer, Keats and Coleridge. Even the sentimental genre paintings of the time. Whilst one eye looked back another was focused on the horizon. She gently pushed at prevalent gender stereotyping. Her women posed in what was then seen as traditionally male fashion, men appeared as historical female figures, and an 1865 shot showed Cameron's maid, Mary Hillier, not for the last time, as Sappho.

Despite the taboo testing her devout Christianity was often to the fore. Not least in a series of Madonna groups featuring, again, Mary Hillier. That maid earned her keep. Mangers, crosses, drapery, flowers, and other signifiers of the holy life were all employed to emphasise the virtuous nature of her beliefs. To modern eyes these are among her weaker works, moralising and twee with a hint of the dreaded chocolate box, but it's worth a deeper look. Incremental technological innovations had come into play whilst darkness, and even some good old fashioned Old Testament death, lurked in the murky margins.

In 1874 Tennyson invited Cameron, and she accepted, to provide illustrations to his Idylls of the King. There's a kind of Moondog vibe to the above piece and it bears witness to her increasing confidence. As did her brave use of soft focus, multiple negatives and combination prints.

Though not to the liking of many critics at the time she had still become both a successful and a commercial artist unashamed, and unabashed, in using her connections to increase her capital. The fact her high society chums were able to sign the portraits before sale didn't hurt none either.

Then, at the height of her fame in 1875, the family moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) where, due to a whole host of logistical problems, her artistic career ended as abruptly as it had began. She'd had barely more than a decade of notoriety and four years later she passed away at the age of 63.

This exhibition does a good job of shedding some light on a photographic pioneer who was certainly not well known to this writer prior to his attendance. It could, perhaps, have compared and contrasted her against contemporaries and gave a better understanding of the time and milieu in which she worked. Then again that could be another show for another day - and probably not a free one either.

Friday, February 19, 2016

A French revolution?

Ferdinand Victor Eugene Delacroix was born in 1798 in the southern suburbs of Paris. Into a country that had recently seen the storming of the Bastille, the Terror, and the executions of Louis XVI and Robespierre amongst countless others. He lived during the first half of a nineteenth century which saw the reign of Napoleon and the later restoration of the French monarchy. Tumultuous times by any reckoning.

The National Gallery's new exhibition 'Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art' eschews the obvious temptation of a chronological approach and instead attempts to reposition our titular hero as one of the fathers of modernism.

Despite his almost permanent ill health and/or hypochondria he was known to his friends as a tiger and appropriately enough did not want to be caged in by the strict parameters of the French academic system which demanded monochrome drawing be mastered before artists were let loose on the colour palette. Instead he looked to contemporary British art of the time (Richard Parkes Bonington, Constable) and, particularly, back to the seventeenth century Flemish artist Rubens. You can see the influence in his Death of Sardanapalus (1846). A picture condemned in the harshest terms by critics of the time for it's sense of improvisation and ambiguity. Too modern perhaps?

Delacroix was not immune to the exoticising orientalism so prevalent then. Following France's invasion of Algeria he travelled to Morocco where his depictions of Jewish weddings and views of Tangiers both inspired Renoir and brought a new dimension to his oeuvre which had been hitherto dominated by historical works. In fact his earlier north African scenes were inspired by readings of Byron rather than visits to the Maghreb. My favourite in this section is 1838's Convulsionists of Tangiers.

Delacroix also helped revive the genre of flower painting. It had become seen as purely decorative (though surely all art is to a point?) despite its historical associations with the philosophical tradition of the memento mori. He set his baskets in gardens, rather than interiors, and incorporated prickly foliage into his canvasses. All the better to bring out the essential untamed nature of his subject.

Romantic myths and heroic tales were his pain et beurre though. From Shakespeare and Byron to the (supposedly) greatest story ever told. His imagination contrived and his technical virtuosity rendered vivid tableaus of Christ on the cross, Ruggiero rescuing Angelica, and the third siege of Missolonghi. His Christ on the Sea of Galilee from 1853 anticipates the looser expressive brush strokes of the Impressionists whilst, at the same time, nodding in the direction of his prematurely deceased contemporary and countryman Theodore Gericault.

His landscapes further inspired artists like Monet, Cezanne, and Whistler. The belief in synaesthesia he shared with Richard Wagner and, perhaps most of all, the Journal published after his death in 1863, gained him yet more admiration from Renoir, Moreau and Fantin-Latour as well as the poet Baudelaire and the novelist Henry James.

Delacroix pointed the way towards modernism. But to these eyes he was not, himself, a modernist. This hits home on entering the gallery's final rooms where you encounter Manet's realism, Gauguin's primitivism, Signac's pointillism, and, most strikingly, Van Gogh's violent expressionism. See below for 1889's Olive Trees. Van Gogh kept a Delacroix in his bedroom in Arles. Gauguin took one to the South Seas with him as he pioneered his early form of sex tourism.

We all need signposts but they shouldn't be confused with destinations. The tour, and it is a worthwhile one, ends with a Kandinsky. Suggesting, possibly, that Delacroix in some way paved the way for pure abstraction. A leap too far, maybe, but an interesting contention and it's a favourite trick of this writer to end on a question rather than an answer. Or is it?

The National Gallery's new exhibition 'Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art' eschews the obvious temptation of a chronological approach and instead attempts to reposition our titular hero as one of the fathers of modernism.

Despite his almost permanent ill health and/or hypochondria he was known to his friends as a tiger and appropriately enough did not want to be caged in by the strict parameters of the French academic system which demanded monochrome drawing be mastered before artists were let loose on the colour palette. Instead he looked to contemporary British art of the time (Richard Parkes Bonington, Constable) and, particularly, back to the seventeenth century Flemish artist Rubens. You can see the influence in his Death of Sardanapalus (1846). A picture condemned in the harshest terms by critics of the time for it's sense of improvisation and ambiguity. Too modern perhaps?

Delacroix was not immune to the exoticising orientalism so prevalent then. Following France's invasion of Algeria he travelled to Morocco where his depictions of Jewish weddings and views of Tangiers both inspired Renoir and brought a new dimension to his oeuvre which had been hitherto dominated by historical works. In fact his earlier north African scenes were inspired by readings of Byron rather than visits to the Maghreb. My favourite in this section is 1838's Convulsionists of Tangiers.

Delacroix also helped revive the genre of flower painting. It had become seen as purely decorative (though surely all art is to a point?) despite its historical associations with the philosophical tradition of the memento mori. He set his baskets in gardens, rather than interiors, and incorporated prickly foliage into his canvasses. All the better to bring out the essential untamed nature of his subject.

Romantic myths and heroic tales were his pain et beurre though. From Shakespeare and Byron to the (supposedly) greatest story ever told. His imagination contrived and his technical virtuosity rendered vivid tableaus of Christ on the cross, Ruggiero rescuing Angelica, and the third siege of Missolonghi. His Christ on the Sea of Galilee from 1853 anticipates the looser expressive brush strokes of the Impressionists whilst, at the same time, nodding in the direction of his prematurely deceased contemporary and countryman Theodore Gericault.

His landscapes further inspired artists like Monet, Cezanne, and Whistler. The belief in synaesthesia he shared with Richard Wagner and, perhaps most of all, the Journal published after his death in 1863, gained him yet more admiration from Renoir, Moreau and Fantin-Latour as well as the poet Baudelaire and the novelist Henry James.

Delacroix pointed the way towards modernism. But to these eyes he was not, himself, a modernist. This hits home on entering the gallery's final rooms where you encounter Manet's realism, Gauguin's primitivism, Signac's pointillism, and, most strikingly, Van Gogh's violent expressionism. See below for 1889's Olive Trees. Van Gogh kept a Delacroix in his bedroom in Arles. Gauguin took one to the South Seas with him as he pioneered his early form of sex tourism.

We all need signposts but they shouldn't be confused with destinations. The tour, and it is a worthwhile one, ends with a Kandinsky. Suggesting, possibly, that Delacroix in some way paved the way for pure abstraction. A leap too far, maybe, but an interesting contention and it's a favourite trick of this writer to end on a question rather than an answer. Or is it?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)