"Nobody gains absolute power unless somebody else lets him gain absolute power".

Christopher Spencer's documentary about David Koresh and the siege (and following conflagration) at the Mount Carmel Center outside Waco, Texas that resulted in eigthy-two deaths in 1993 was an even-handed, comprehensive, empathetic, and emotionally literate piece of film making and in its inclusion of interviews with nine of the survivors (as well as FBI men who had been present, and involved, at the time) it had something of an ace up its sleeve.

It made, at times, for troubling viewing (one of the first lines we hear is "I just remember the babies headstones") but it was also a fascinating, absorbing insight into what makes a man become a cult leader, why people are attracted to follow that man/cult, and what lessons could be learned in the way the FBI, the ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives), the US government, and the media covered it. The motive of every involved party is examined and nobody is left entirely off the hook. Even the general public come in for a mild rebuke for their part in proceedings.

Usefully, too, there is plenty of build up showing us events that happened years before the siege (sometimes using dramatic reconstruction, sometimes witness testimony). Koresh is described as a con man with a bible in one hand and a machine gun in another, very much the archetype of your Southern Gothic preacher steeped in Old Testament ideas of fire and brimstone, yet he bewildered, beguiled, and mesmerised his followers. Some of whom called him God and some of whom, even now, miss their life in the cult under Koresh. A cult we know, mostly because of Koresh, as the Branch Davidians.

Survivors make comparisons with Jesus Christ, another leader executed for his beliefs at the age of 33, and Koresh, himself, said "what if I am the messiah?". Something he increasingly went on to believe. President Bill Clinton took a somewhat different view calling Koresh "dangerous, irrational, and probably insane".

It's a view it's hard not to endorse but the interviews with survivors like Heather Burns, Kathy Jones, Charles Pace, Liz Baranya, Kathy Schroeder, and Livingston Fagan (from the UK and Australia as well as the US and a racially mixed bunch to boot) reveal, for the most part, normal (whatever that is) folk, just trying to navigate their way through life. It'd be instructive to learn what had bought them to Koresh, to the Branch Davidians. Did they lack something in their own families? Did they want for some deeper emotional belonging of a type that can't be found in the cruel capitalist society we all must live under?

That we don't find out is one of the only missteps in the nearly 3hr running length (I believe edited down from an original four hour duration). We do, however, get a fairly rounded portrait of what Koresh's life was before he began identifying as the son of God.

Born Vernon Howell (the name change wasn't official until 1990), he'd been a stuttering, stammering, dyslexic kid who'd suffered bullying at school (like many many others before and after) who'd grown up into a long haired, hippy guitarist dude who travelled to Mount Carmel in 1981 to join the Branch Davidians who, by that point, had already been based there for twenty-six years.

As with all religions and all cults (they're, basically, the same thing) there is a confusing history of schisms and power struggles that led to their existence but the gist, as far I can work out, is that they were formed from the ashes of Victor Houteff's organisation, The Shepherd's Rod, a Davidian Seventh-Day adventist group. On Houteff's death (in 1955) that group was taken over by Benjamin Roden and when Roden died in '78, that passed to his widow Lois.

Lois (by then considered the prophet) loved fancy cars, fancy clothes, fancy shoes, and, of course, power (as befits a cult leader) but she also loved, it seems, David Koresh, and the two of them entered into a relationship. Koresh was in his twenties, Lois in her sixties. She was old enough to be his grandmother.

She miscarries his baby, the fact she got pregnant in the first place is the most surprising thing here, which Koresh says is because of her lack of faith. A lack of faith that meant he would have to take over as spiritual leader. Lois no longer served any purpose so Koresh and a few of his associates threw her out of the back of a moving truck. God had spoken to Koresh and, as we're often told, God works in mysterious ways. If God wants us to throw old age pensioners from the back of moving trucks, who are we, mere humans, to question him?

In 1985, Koresh visited the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem where he claims, and he would - wouldn't he?, to have had a divine visitation. A chariot of angels had taken him beyond Orion to interact with advanced civilisations who had developed laser technologies and were able to provide him with a panoramic understanding of the Bible in its entirety.

The Bible is a problematic book in many ways but perhaps mostly in how widely it can be interpreted. Koresh, described by one of his followers as "charismatic but full of truth", chose to interpret both the Bible, and his regular chats with God (the boss), as a message that there was no need for him, or his followers, to lead a normal life, no need to invest in the future, no need to plan, because God was coming to save them - and he was coming soon.

He became obsessed with the Book of Revelation and the Seventh Seal, eschatological representations of Babylon and those oppressed by Babylon. He not only 'knew' only the lamb of God could open the seven seals but he was convinced he was that lamb of God and he came to see that the USA was the Babylon that he, and his followers, were fighting against.

To toughen them up for the oncoming 'tribulations' he had them working out on obstacle courses but when the apocalypse resolutely refused to arrive in Waco, Koresh went looking for it. A self-fulfilling prophecy in the most literal way imaginable.

The glorification of death is always one of the worst parts of any Abrahamic faith. Another obstacle, far bigger than anything on Koresh's crazy version of the Krypton Factor, for any right minded person would be the worship, to the point of fetishisation, of virginity. Koresh used it to justify his paedophilia.

Koresh had children with some of the girls (and they were girls, often under age) in Mount Carmel and, as his messiah complex grew stronger and stronger, he formulated an idea called the New Light which forbade physical contact, even holding hands, between husbands and wives in his movement. The women, those of child bearing age, should save themselves for Koresh and Koresh only. This way they could have his babies, righteous babies. He claimed ownership of all the women in the world and women at Mount Carmel, in true ISIS style, were forced to burn pictures of their husbands.

The penny dropped for some that they were in a cult and a few escaped. Midnight flits were the order of the day (one girl, seemingly unaware she's paraphrasing the lyrics to Middle of the Road's 1970 smash 'Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep', claims she "woke up one morning and momma was gone") and' once on the other side, some escapees tried to get the authorities to investigate what was happening, the paedophilia specifically. Nobody cared.

They started caring two years later when gunshots were heard inside Mount Carmel and a UPS driver informed the sheriff that he'd been tasked with delivering hand grenades there. It came at a good time for the ATF. They were trying to attract funding and an armed cult in Texas looked great for their case. They rented a house across from the compound and sent an interloper in.

His name was Robert Rodriquez, he's interviewed for the film, and, soon, Koresh, set about trying to convert him. It didn't work and once Rodriquez had confirmed the stockpiling of weapons a search warrant was granted for 28th February 1993. 'Showtime' as some refer to the planned morning raid now and, like so many other 'show's', the media had been tipped off. Not useful when the element of surprise was paramount.

It wasn't long before the shooting started and most accounts say it was the ATF who fired first. One member of the Branch Davidians reported the ATF to the FBI. Another one shot himself and joined the six who'd been shot dead by the ATF. Four ATF agents, too, were dead. Koresh was wounded and the Branch Davidians were concerned he may die and they'd be left without spiritual guidance.

The siege had begun and the FBI had now got involved. Koresh agreed he'd send the children out - the ones that he had not fathered at least - and he was true to his word on this. Once on the other side, the children were treated to sweets, sugar, and freedom. They loved it. They did not appear to miss David Koresh or Mount Carmel whatsoever.

Video footage of the children enjoying themselves was sent back into the compound with the intention of tugging on the heartstrings of the parents still there. It backfired. Badly. Within David Koresh's Branch Davidians, maternal and paternal instincts were very much secondary to being a servant of God.

After eighteen children and two adults had been released things seemed to be improving. But then two things happened that could only have made things worse. Firstly an FBI sniper team arrived "honed to kill" and, secondly, Koresh reneged on his own promise to come out. He claimed he'd spoken to God and God had told him to stay put.

By this time Waco had become a worldwide news story and there were even t-shirt vendors setting up on the perimeters of the compound to make money out of tourists who'd come to rubberneck at events. One of which, and you can see him on the film, was Timothy McVeigh, who, two years later, would blow up the Alfred P.Murrah Building in Oklahoma City killing 171 people in an act of far right terrorism.

As reporters outside the compound described "a carnival atmosphere", inside it the carnival was (nearly) over. A huge banner was raised reading "GOD HELP US WE WANT THE PRESS" and one more child was permitted to leave the compound.

Her description of her walk from Mount Carmel to the waiting police is utterly chilling. She wasn't sure if she'd be shot in the back by the cult she was leaving or shot in the front by the people she was walking towards. Luckily, neither happened, but her teddy bear was shredded to pieces in case it contained a hidden bomb. Worse still, much worse, she was the last ever child to leave the Mount Carmel Center alive. Koresh's children may have had 'God's DNA' but they would die alongside him.

Koresh was accused of manipulating religion and even though apologists for Koresh refute this, and it does seem that the FBI could be crassly insensitive and that they made dangerous tactical and strategical errors, but, really, religion is all about interpretation and interpretation and manipulation make the easiest of bedfellows. Everyone will interpret beliefs in the way they want to. The 'Bible babble' that is mentioned in the film is a real, and dangerous, thing.

One thing the FBI can't be accused of is not providing the manpower. It's stated that, for Waco, the FBI formed possibly the largest US army ever to be deployed against civilians. There were over seven hundred 'soldiers' involved. They possibly didn't deploy their greatest brains. In an echo of the bizarre events during the US invasion of Panama and the toppling of Manuel 'Pineapple Face' Noriega, a few years earlier, the FBI started to blast the compound with music and sound, Nancy Sinatra's 'These Boots Were Made For Walkin'" joined an avant-garde playlist of cocks crowing, clocks ticking, and the sound of rabbits being slaughtered. Achy Breaky Heart on a continuous loop, however, was ruled out. You can go too far.

The left hand didn't know what the right hand was doing. FBI negotiators, who felt they were making some headway, were unaware the tactical team were using these disorientation techniques. Also, Koresh didn't seem overly phased by it. He just blasted his own music back at them. The siege was turning into a fucking soundclash.

All this just led to the Branch Davidians rallying round their leader. One follower, Kathy Schroeder, did, however, ask Koresh if she could leave. Koresh allowed her to do so and, interviewed now, Schroeder is still angry, still talks as if her 'side' did nothing wrong, and, for the most part, makes herself very difficult to like.

Another tactic that backfired was when the FBI tried to get the Branch

Davidians to turn on their leader. They seemed unaware of how

indoctrinated by him, and in how thrall to him, they had become. They tried to drive a wedge between Koresh and his number two, Steve Schneider, using the fact that Koresh had had a kid with Schneider's wife (and Schneider had not been able to) but that didn't work either. The next man out was the erudite and eccentric UK national Livingstone Fagan who was immediately put in a proto-Guantanamo orange jumpsuit.

Koresh was eventually sold the idea that he could write a book revealing his message and once done he could leave the compound. Koresh said it would take him a fortnight to write this book and he got to work on dictating it to Steve Schneider's wife, Judy, who typed it up. Koresh's spelling was atrocious so heavy editing was required.

Some took Koresh at his word, others felt he was playing for time. In Washington DC, the government had been informed that with each hour he was left in the compound, the likelihood of him molesting the, his own, children grew stronger. So on day 51 of the siege, it was decided, the FBI were going in.

They were pretty gung-ho about it too, this was what many of them had trained for. Tear gas was released into the building. The adults among the Branch Davidians all had gas masks but there were none that fitted the children. The FBI gassed them for six hours solid, Koresh handed out grenades, and the building caught fire. Still, Koresh would not let the children out.

They needed to die - like in the Bible. The remaining Branch Davidians now seem proud of those who remained in the compound (even if it was against their will) for putting God above their own life. They seem guilty that they didn't die more than they feel guilty that they let their own children burn to death. Nine adults were able to save themselves from the conflagration and each of them left their own children to die (although one saved a dog). Truly, Christianity is a death cult.

All in all, seventy-six Branch Davidians died in the flames, twenty-three of them were children. David Koresh was shot in the front of his head. To this day, nobody knows if he was shot by an FBI agent, one of his own followers, or by his own hand.

Also to this day, sadly, there are those who claim his 'book' had substance, those who say that God had judged Koresh harshly for misinterpreting scripture, and those who still believe that David Koresh was God. And in some ways, he was. Because God exists only in the mind and there's always a new God coming along to replace the last one, to force his (and it's almost always a 'his') will on weaker people, to exploit people's fears, and to ruin people's lives. God never ever does the decent thing and just fucks off and leaves us to it. No, God ensures that people never stop suffering. It doesn't matter if David Koresh was God or not because God is a load of made up bullshit and it's time everyone moved on and stopped killing each other in his name.

This was an excellent film and both a chilling and thought provoking watch. The story told was profoundly depressing but more depressing still is the knowledge that events like this will continue to happen time and time again.

Sunday, 27 January 2019

Thursday, 24 January 2019

Theatre night:Rosenbaum's Rescue.

"Life without experience and suffering is not life" - Socrates.

I had a good feeling about A Bodin Saphir's Rosenbaum's Rescue but I certainly didn't expect to come away convinced it was one of the best plays I've ever been privileged to see in my entire life. I laughed, I wept, I had both my presumptions and prejudices questioned and challenged, and I even managed to learn a little bit about the history of Denmark during World War II.

My hopes were met easily - and then exceeded. Set over the course of two cold nights in 2001 in Abraham and Sara's remote Danish house, the observant Jew and his 'Swedish' wife welcome their old friend Lars and his grown up daughter Eva to a night of drinks and Scrabble. Their history, it is apparent from the very start, goes back a very long way - and is very checkered. Just how much so will unravel as the play develops.

The catch-up soon develops into an, at times, heated discussion about the evacuation, and rescue, of most of the Danish Jewish population in 1943, following an order from Adolf Hitler that they should all be arrested, deported, and 'processed'. Remarkably, I was unaware of this (true) story beforehand and on its own it would have made for a compelling and emotional drama. But Bodin Saphir's play delves into his own family's personal experiences and, in the character of historian Lars, seeks to uncover the truth of what really happened during that whole episode. It may not have been exactly as the record books claim.

The exchanges between all four characters never forget to put the personal into the political but in a style that may be familiar to admirers of the work of Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, the story is peppered with revelations of an entirely personal nature. Be they as quotidian as fixing a broken pipe, lighting the candles for Hanukkah or others, far more earth shattering, that I shall not reveal. Spoiler alerts and all that.

As each plot twist reveals new layers to each character you find your sympathy continually switching around the stage (a fairly straightforward set up, one front room, one kitchen) from Abraham to Lars to Eva and back to Sara. In a tightly plotted two hours, the script manages to touch on, even go quite deep into, subjects as various and vital as sexuality, nationhood, faith (or lack of it), immigration, memory, religion, our sense of identity, and the fragile nature of the male ego.

The way Abaraham and Lars deal with their occasionally bruised pride is an important part of the make up of Rosenbaum's Rescue but it is the eloquent dialogue that elevates this play above so many others. Exposition is only provided when absolutely necessary, elsewhere we're given the responsibility of thinking for ourselves, and there's barely an ounce of fat on a single line spoken by any character. If only exchanges between me and my family were this neat.

As Abraham, David Bamber has the nebbishness down to a level I'd almost consider a cliche if it wasn't for a loud Jewish lady regularly squealing with recognition a few seats along from me, and Neil McCaul plays Lars as one of those haughty, I know best, intellectuals whose disdainful manner tends to make more enemies than it wins arguments, it's safe to say he is a man who does not wear his education lightly.

Dorothea Myer-Bennett, like everyone else, is excellent as Eva, the somewhat estranged daughter of Lars who, by dint of her German mother, identifies more as German than Danish. She's articulate, learned, and yet eager to learn and listen at all times. Julia Swift's Sara, too, has to occasionally make do with standing to the side while the men verbally duke it out. That's not to belittle her role but to comment on how accurate an observation of married life Bodin Sapher was able to conjure up. Swift, for the record, was brilliant.

But, ultimately, each of the four cast members owe an enormous debt to Alexander Bodin Saphir who not only taught me who Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz and Karl Rudolf Werner Best were but reminded me that though we must always seek truth sometimes we may have to learn to accept that we might not like the truth we find. If I knew that already, and I think we all do, then Rosenbaum's Rescue underlined it to me in the most exquisite way imaginable. All that on a Thursday night in Finsbury Park.

I had a good feeling about A Bodin Saphir's Rosenbaum's Rescue but I certainly didn't expect to come away convinced it was one of the best plays I've ever been privileged to see in my entire life. I laughed, I wept, I had both my presumptions and prejudices questioned and challenged, and I even managed to learn a little bit about the history of Denmark during World War II.

My hopes were met easily - and then exceeded. Set over the course of two cold nights in 2001 in Abraham and Sara's remote Danish house, the observant Jew and his 'Swedish' wife welcome their old friend Lars and his grown up daughter Eva to a night of drinks and Scrabble. Their history, it is apparent from the very start, goes back a very long way - and is very checkered. Just how much so will unravel as the play develops.

The catch-up soon develops into an, at times, heated discussion about the evacuation, and rescue, of most of the Danish Jewish population in 1943, following an order from Adolf Hitler that they should all be arrested, deported, and 'processed'. Remarkably, I was unaware of this (true) story beforehand and on its own it would have made for a compelling and emotional drama. But Bodin Saphir's play delves into his own family's personal experiences and, in the character of historian Lars, seeks to uncover the truth of what really happened during that whole episode. It may not have been exactly as the record books claim.

The exchanges between all four characters never forget to put the personal into the political but in a style that may be familiar to admirers of the work of Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, the story is peppered with revelations of an entirely personal nature. Be they as quotidian as fixing a broken pipe, lighting the candles for Hanukkah or others, far more earth shattering, that I shall not reveal. Spoiler alerts and all that.

As each plot twist reveals new layers to each character you find your sympathy continually switching around the stage (a fairly straightforward set up, one front room, one kitchen) from Abraham to Lars to Eva and back to Sara. In a tightly plotted two hours, the script manages to touch on, even go quite deep into, subjects as various and vital as sexuality, nationhood, faith (or lack of it), immigration, memory, religion, our sense of identity, and the fragile nature of the male ego.

The way Abaraham and Lars deal with their occasionally bruised pride is an important part of the make up of Rosenbaum's Rescue but it is the eloquent dialogue that elevates this play above so many others. Exposition is only provided when absolutely necessary, elsewhere we're given the responsibility of thinking for ourselves, and there's barely an ounce of fat on a single line spoken by any character. If only exchanges between me and my family were this neat.

As Abraham, David Bamber has the nebbishness down to a level I'd almost consider a cliche if it wasn't for a loud Jewish lady regularly squealing with recognition a few seats along from me, and Neil McCaul plays Lars as one of those haughty, I know best, intellectuals whose disdainful manner tends to make more enemies than it wins arguments, it's safe to say he is a man who does not wear his education lightly.

Dorothea Myer-Bennett, like everyone else, is excellent as Eva, the somewhat estranged daughter of Lars who, by dint of her German mother, identifies more as German than Danish. She's articulate, learned, and yet eager to learn and listen at all times. Julia Swift's Sara, too, has to occasionally make do with standing to the side while the men verbally duke it out. That's not to belittle her role but to comment on how accurate an observation of married life Bodin Sapher was able to conjure up. Swift, for the record, was brilliant.

But, ultimately, each of the four cast members owe an enormous debt to Alexander Bodin Saphir who not only taught me who Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz and Karl Rudolf Werner Best were but reminded me that though we must always seek truth sometimes we may have to learn to accept that we might not like the truth we find. If I knew that already, and I think we all do, then Rosenbaum's Rescue underlined it to me in the most exquisite way imaginable. All that on a Thursday night in Finsbury Park.

Wednesday, 23 January 2019

Flog It! The Sanctified and Violent Art of Jusepe de Ribera.

Jusepe de Ribera lived in violent times and Jusepe de Ribera, by most accounts, was a violent man. So, it's no surprise that the Dulwich Picture Gallery's Ribera:Act of Violence should be dominated by violent imagery. It's even in the name of the show!

It comes, mostly, in the form of saints being flayed or flogged, but Ribera didn't limit himself to the Christian celebration of death and violence. He branched out to show us mere mortals being hanged, tortured, and undergoing various other humiliating and painful looking indignities, often in full view of the Venetian public.

A Venetian public who seemed so inured to the violence in their midst they barely paid attention to it. Of course, the Dulwich Picture Gallery is both an august and an orderly establishment and it would never host a show for the sole purpose of providing cheap titillation so, before you can get to that, you're treated to some history about the life, times, and art of Jusepe de Ribera.

It comes, mostly, in the form of saints being flayed or flogged, but Ribera didn't limit himself to the Christian celebration of death and violence. He branched out to show us mere mortals being hanged, tortured, and undergoing various other humiliating and painful looking indignities, often in full view of the Venetian public.

A Venetian public who seemed so inured to the violence in their midst they barely paid attention to it. Of course, the Dulwich Picture Gallery is both an august and an orderly establishment and it would never host a show for the sole purpose of providing cheap titillation so, before you can get to that, you're treated to some history about the life, times, and art of Jusepe de Ribera.

Jusepe de Ribera - Saint Bartholomew (c.1612)

Known as Lo Spagnoletto (the Little Spaniard), Ribera was born in the province of Valencia in 1591 and by his mid-twenties he had decamped to Naples, then Spanish territory, to escape his creditors after living high on the hog for a few years in Rome. He never returned to Spain.

As a teen he'd encountered the work of Caravaggio, two decades his senior, and it is clear how the acknowledged master of chiaroscuro, and another artist who had 'issues', became Ribera's chief influence and, it would seem, role model. His chief subject, if we are to believe the curators of this show - and I see no reason not to, would become Saint Bartholomew.

Above we can see an early work, the date suggests it was carried out in Rome, that focuses not so much on Bartholomew himself but the hard looking bastard who flayed his skin off. He's still brandishing the knife in his right hand as he stares dead eyed out at us, mentally asking us if we fancy our chances. But what's that in his right hand? Oh, it's what's left of Bartholomew. His skin and his face. It really is quite a disturbing painting and it really is quite a disturbing story. Were Christians simply reflecting the violent world they lived in or were they glorifying it?

Bartholomew the Apostle is said to have travelled around Armenia and India spreading the word of Jesus, and it was in India, rumour has it near Mumbai, that he met his grisly end. Art tends to focus on the flaying but he's also said to have had his head chopped off and been hung upside down, just like Saint Peter.

Bartholomew the Apostle is said to have travelled around Armenia and India spreading the word of Jesus, and it was in India, rumour has it near Mumbai, that he met his grisly end. Art tends to focus on the flaying but he's also said to have had his head chopped off and been hung upside down, just like Saint Peter.

Jusepe de Ribera - The Martyrdom of St Bartholomew (c.1628)

That explains how he ended up the patron saint of tanners, trappers, bookbinders, butchers, barber surgeons, and even Armenia (though does less to explain him being put in charge of cheese, salt, and, er, twitching - there's a patron saint of twitching!). At Dulwich, we can compare Ribera's incremental improvement with two Martyrdom of St Bartholomew's created roughly fifteen years apart.

Both feature the broken classical sculptural head, Ribera's way of saying his art is not an art beheld to classicist notions - but one determined to see the world as it really is, and both, as was the behest of the Roman Catholic church at the time, are intended to arouse a strong emotional sense of piety in the viewer. This works better in the later work as Bartholomew, his body twisted and torn, looks straight out to us urging us to 'contemplate our own spiritual purity'.

Jusepe de Ribera - The Martyrdom of St Bartholomew (c.1644)

Among the etchings, ink and washes, chalk preparatory sketches, tribunal documentation, and, of course, more scenes of torture there's a whole room devoted to Ribera's rendering of skin. Skin is a big part of what we are. Our ethnicity and our features are discernible in our skin, we describe people as 'comfortable in their own skin', we say we have 'skin in the game', and we describe feelings (or wounds) as 'skin deep'. Without our skins we'd not recognise each other (especially as we'd be dead) but Bartholomew the Apostle managed to contradict that. He's now best known for not having any skin. If skin makes us, then it was the unmaking, the flaying, of Bartholomew that made him.

Oddly enough, the only full scale painting in the 'skin' room is a work Ribera has made that focuses on our sense of smell. It's suggested that not only the onion and the garlic, but even the beggar himself, would be an assault on our senses and though it's a wonderful painting, those corners are so so dark, it's hard to be offended by an onion, or even some BO, when you're looking back to an era in which torture and execution were both common and played out as public spectacle. That'd be like getting angry about a football match when there are children drowning in the Mediterranean.

Oddly enough, the only full scale painting in the 'skin' room is a work Ribera has made that focuses on our sense of smell. It's suggested that not only the onion and the garlic, but even the beggar himself, would be an assault on our senses and though it's a wonderful painting, those corners are so so dark, it's hard to be offended by an onion, or even some BO, when you're looking back to an era in which torture and execution were both common and played out as public spectacle. That'd be like getting angry about a football match when there are children drowning in the Mediterranean.

Jusepe de Ribera - Sense of Smell (c.1615)

Jusepe de Ribera - Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women (c.1620-3)

To give you a feel for how bloodthirsty the era was there's a selection from Jacques Callot's Miseries of War series that would go on to inspire Goya. Callot was a contemporary of Ribera and with the Thirty Years War (the deadliest war ever in Europe at that time) as his subject matter, he had quite a lot to be horrified/inspired by.

The Thirty Years War didn't reach Naples so Ribera made do with more everyday violence, there's an astounding painting of a man on a 'strappado' outside Naples' Tribunale della Vicaria to give us a feel for how taken for granted torture was at the time, to inspire his images of suffering saints. When it wasn't Bartholomew coming to an undignified end, it was Sebastian getting it in the neck. Often, quite literally.

Sebastian was either tied to a tree, shot through the neck with arrows or clubbed to death, accounts vary, for refusing to denounce his Christian faith to the emperor Diocletian. Ribera's painting shows him being tended by holy women. One of them appears to be picking a splinter from his bare thigh and though that's hardly enough to crack one out over there are, often in this show, suggestions of a link between violence and eroticism.

Lustful satyrs, whips, randy old goats, etc; It's nothing new to suggest that the thin line between pleasure and pain can, at times, be rendered almost invisible. But the Christian idea of sex, or certain variants of sex, as sinful was only ever going to make it more appetising. We all want to bite that juicy red apple and we'd probably not even be put off by somebody in the act of defecation nearby. Certainly, these squatting shitters seem to hover in the background of many a Ribera sketch.

The final room contains just one, large painting and is, of course, suitably hushed and reverent. That's what happens when you put just one painting in a room and dim the lights. People feel they have to sit and look at it for longer than the other paintings. They almost feel they have to meditate. I've certainly heard people describe their experiences in Tate Modern's Rothko room that way.

Ribera is a very different artist to Rothko but I'm not sure their intentions were so far apart. I think they both desired quiet contemplation in front of their work and if Ribera wished to instruct more than Rothko, that's probably more a reflection of the different eras they operated in than their personalities. 1637's Apollo and Marsyas shows Apollo (the god of music) beating the satyr, Marsys, in a musical contest and flaying the skin from his 'hide' to celebrate victory.

It's not something they tend to do on X-Factor (thouugh it may be where the idea of an ass-whooping comes from). But then nor did they play lyres upside down, even Jimi Hendrix didn't do that, like Apollo does. Apollo is/was a Greek/Roman god rather than a Christian one but the message changes little with religions. Hubris should be punished and punished, of course, with violence. It's debated whether or not religion causes violence or if violence leads to religion but it certainly seems, if you look at any art or look at any particularly religious country, that wherever one is you can be certain the other won't be far away.

Sebastian was either tied to a tree, shot through the neck with arrows or clubbed to death, accounts vary, for refusing to denounce his Christian faith to the emperor Diocletian. Ribera's painting shows him being tended by holy women. One of them appears to be picking a splinter from his bare thigh and though that's hardly enough to crack one out over there are, often in this show, suggestions of a link between violence and eroticism.

Lustful satyrs, whips, randy old goats, etc; It's nothing new to suggest that the thin line between pleasure and pain can, at times, be rendered almost invisible. But the Christian idea of sex, or certain variants of sex, as sinful was only ever going to make it more appetising. We all want to bite that juicy red apple and we'd probably not even be put off by somebody in the act of defecation nearby. Certainly, these squatting shitters seem to hover in the background of many a Ribera sketch.

The final room contains just one, large painting and is, of course, suitably hushed and reverent. That's what happens when you put just one painting in a room and dim the lights. People feel they have to sit and look at it for longer than the other paintings. They almost feel they have to meditate. I've certainly heard people describe their experiences in Tate Modern's Rothko room that way.

Ribera is a very different artist to Rothko but I'm not sure their intentions were so far apart. I think they both desired quiet contemplation in front of their work and if Ribera wished to instruct more than Rothko, that's probably more a reflection of the different eras they operated in than their personalities. 1637's Apollo and Marsyas shows Apollo (the god of music) beating the satyr, Marsys, in a musical contest and flaying the skin from his 'hide' to celebrate victory.

It's not something they tend to do on X-Factor (thouugh it may be where the idea of an ass-whooping comes from). But then nor did they play lyres upside down, even Jimi Hendrix didn't do that, like Apollo does. Apollo is/was a Greek/Roman god rather than a Christian one but the message changes little with religions. Hubris should be punished and punished, of course, with violence. It's debated whether or not religion causes violence or if violence leads to religion but it certainly seems, if you look at any art or look at any particularly religious country, that wherever one is you can be certain the other won't be far away.

Jusepe de Ribera - Apollo and Marsyas (1637)

Thanks to Dan for joining me on my first of two visits to this show (we were treated to a modern dance interpretation in the mausoleum by Animalis!) and for lifting my spirits with a cup of tea and a chat.

Tuesday, 22 January 2019

Christs Alive!:- When Mantegna met Bellini.

"For what shall it profit a man, if he gain the whole world, and suffer the loss of his soul?" - Jesus Christ.

Jesus Christ is everywhere in the National Gallery's current Mantegna and Bellini exhibition. There are dead Christs, living Christs, Christs that are somewhere between life and death, baby Christs, adult Christs, realistic looking Christs, unrealistic looking Christs, and Jesus in a Limo.

Well, not the last one - obviously. But, Christ on a bike, that is one hell of a lot of son of Gods to have to take in on a Monday afternoon. I reckon 15c Venice would have been even busier Christwise though. They were religious times - and Venice was a religious city, as most (all?) were in Europe at the time. Far be it from me to chat shit about Renaissance art but there are times when you begin to wonder if they didn't overdo the God a little bit. Renaissance complacence is a thing, you know.

Anyway, this particular Renaissance tale begins when Padua's new sensation Andrea Mantegna marries Nicolosia Bellini, daughter of Jacopo, sister of both Giovannia and Gentile, and, as such, joins one of the most respected and established of Venetian art dynasties.

There's a couple of Jacopo's works early on but there's nothing by Gentile and nothing even about Nicolosia. This show is all about the relationship between Andrea Mantegna and his brother-in-law Giovanni Bellini. How they influenced each other, what each of their strengths was, and what happened when, eventually, they went their own separate ways? What marks did they make on each other and the way they painted? I'll 'fess up straight away that I won't be able to tell you. I'm not E.H.Gombrich.

Jesus Christ is everywhere in the National Gallery's current Mantegna and Bellini exhibition. There are dead Christs, living Christs, Christs that are somewhere between life and death, baby Christs, adult Christs, realistic looking Christs, unrealistic looking Christs, and Jesus in a Limo.

Well, not the last one - obviously. But, Christ on a bike, that is one hell of a lot of son of Gods to have to take in on a Monday afternoon. I reckon 15c Venice would have been even busier Christwise though. They were religious times - and Venice was a religious city, as most (all?) were in Europe at the time. Far be it from me to chat shit about Renaissance art but there are times when you begin to wonder if they didn't overdo the God a little bit. Renaissance complacence is a thing, you know.

Anyway, this particular Renaissance tale begins when Padua's new sensation Andrea Mantegna marries Nicolosia Bellini, daughter of Jacopo, sister of both Giovannia and Gentile, and, as such, joins one of the most respected and established of Venetian art dynasties.

There's a couple of Jacopo's works early on but there's nothing by Gentile and nothing even about Nicolosia. This show is all about the relationship between Andrea Mantegna and his brother-in-law Giovanni Bellini. How they influenced each other, what each of their strengths was, and what happened when, eventually, they went their own separate ways? What marks did they make on each other and the way they painted? I'll 'fess up straight away that I won't be able to tell you. I'm not E.H.Gombrich.

Andrea Mantegna - Presentation of Christ at the Temple (c.1454)

There's a lot of comparing and contrasting works of, and about, the same subjects that both artists made and, in the first instance, there is the somewhat bizarre example of Bellini 'tracing' round one of Mantegna's earlier works, Presentation of Christ at the Temple, and then bunging a couple of extra figures in on each flank. Bellini's Jesus has got a smaller head, Joseph's coat (of not so many colours after all) is more purple but, other than that, it's uncertain as to why this work was executed - and there's little here to tell us. There's a Saint Jerome by each of 'em too. Marginally more different than their Christs but hardly to a noteworthy degree.

I suppose when dealing with Christianity (as with all other religions) looking for logic is beside the point. Religious art is bonkers, surely, for the simple reason that religion is utterly bonkers. That doesn't make it uninteresting. As a confirmed atheist of many decades standing, I appreciate churches for their architecture, gospel music for the way it makes me feel, and religious art for its skill. What underpins them all, for me, is not so much God, as the human capacity for invention. In fact, I'd go so far as to say the invention of God is perhaps one of the greatest, and sadly one of the most deadly, pieces of art us humans have ever come up with.

I digress, it's my blog -I'll do as I please. We're informed on entry to the exhibition, and we can soon see for ourselves, that Mantegna was big on invention, storytelling, and bringing 'life' to classical antiquary whereas Bellini had a less showy talent. Light, colour, and working up of the landscapes were where his strengths lied.

I digress, it's my blog -I'll do as I please. We're informed on entry to the exhibition, and we can soon see for ourselves, that Mantegna was big on invention, storytelling, and bringing 'life' to classical antiquary whereas Bellini had a less showy talent. Light, colour, and working up of the landscapes were where his strengths lied.

Giovanni Bellini - Presentation of Christ at the Temple (c.1470)

Andrea Mantegna - Saint Mark the Evangelist (c.1448)

Perhaps being born into virtual aristocracy gave Bellini the confidence, and the security, to work with small gestures and, perhaps - just perhaps, Mantegna's more lowly birth made him more determined to make grand statements. When nobody is listening to you, it's easy to see why shouting may seem the only viable option. Or, more likely - though no good for the word count, they were just both good artists with different styles.

Though not that different. That's the thing when you go back to this era. Unless, you've got a very very discerning eye (and, sadly, I do not - I fake it) it's really difficult to tell your Leonardos from your Michelangelos, your Piero della Francescas from your Fra Angelicos, and, indeed, your Mantegnas from your Bellinis. I soldiered on in the hope of the kind of divine revelation it seems likely both these artists would have cited as behind their work.

It didn't come with Mantegna's Saint Mark the Evangelist, just a bloke with a beard, but I was more impressed with both his, and Bellini's, take on The Agony in the Garden. It's hard to tell with my crap photos taken off a computer screen (photography was not permitted in the exhibition, unlike in the same gallery's recent Courtauld Impressionists exhibition) but you can probably just about make out that Bellini left much more room for the background whilst Mantegna focused more on the figures.

Though not that different. That's the thing when you go back to this era. Unless, you've got a very very discerning eye (and, sadly, I do not - I fake it) it's really difficult to tell your Leonardos from your Michelangelos, your Piero della Francescas from your Fra Angelicos, and, indeed, your Mantegnas from your Bellinis. I soldiered on in the hope of the kind of divine revelation it seems likely both these artists would have cited as behind their work.

It didn't come with Mantegna's Saint Mark the Evangelist, just a bloke with a beard, but I was more impressed with both his, and Bellini's, take on The Agony in the Garden. It's hard to tell with my crap photos taken off a computer screen (photography was not permitted in the exhibition, unlike in the same gallery's recent Courtauld Impressionists exhibition) but you can probably just about make out that Bellini left much more room for the background whilst Mantegna focused more on the figures.

Andrea Mantegna - The Agony in the Garden (c.1455-6)

Giovanni Bellini - The Agony in the Garden (c.1458-60)

They're both good paintings and I'd find it hard to pick a winner. But when it comes to their take on the crucifixion, Mantenga wins hands downs. Bellini's crucifixion (which I've not included) is a fairly bog standard affair, a skinny Christ looking a bit forlorn. But Mantegna's really gone to town with his. Spectacular hills and skies frame the sight of Jesus and the two 'robbers' nailed up as crowds in spectacular robes, and even a horse, mourn or observe their death. On the ground sit a group of what I presume to be guards, or some other minor officials, who are so disinterested in the death of Jesus Christ they're having a game of dice. If you think it's a shame they're missing such a pivotal event then don't worry. Remember, he would rise to die again. Repeats. Even back in those days.

Andrea Mantegna - The Crucifixion (c.1456-9)

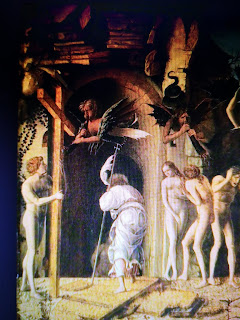

Giovanni Bellini - The Descent of Christ in Limbo (c.1475-80)

Religious scene follows religious scene and I start coming round to them, you can see how people get sucked in, but I think that's more down to the quality of the art than any 'message' inherent. We learn that although Mantegna was 'self-made' he studied Donatello intensely, we see in the Pieta - the Christ of constant sorrows - that Mantegna seemed to get more of a kick out of torturing Jesus than Bellini did, and some cat called Marco Zoppo keeps rocking up.

Zoppo was a Bolognese contemporary of Mantegna and he seems to be something of a third wheel in the bromance between Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini. A bromance that was to end, or at least to be continued from afar, in 1660 when Andrea Mantegna upped sticks and left Venice for Mantua (a beautiful, if rather dull, city I had the pleasure of visiting back in 2014) while Bellini stayed on in the City of Bridges, La Dominante

Giovanni Bellini - Pieta (c.1457)

Andrea Mantegna - Samson and Delilah (c.1500)

Andrea Mantegna - The Death of the Virgin (c.1460-4)

Here their art diverged too. Though traces of each other's influences remained, as they so often do. The 'triumphs' Mantegna painted to celebrate Julius Caesar's victory over Gaul in Mantua's Ducal Palace are so huge that there's barely enough room to stand back far enough in the gallery to take them all in. This is palatial art in all senses of the word and it features a parade of elephants, elaborate processsions, and golden candelabras.

Yet Mantegna, as if remembering Bellini, was turning his hand to smaller, more intimate, personal work to. Witness, for example 1500's Samson and Delilah. The classic statues of the lovers greyed out against a fiery, bright red background as if the passion has left their bodies and gone to nature. It was a landscape, us visitors were informed, inspired by the Early Netherlandish art of Jan van Eyck.

Bellini, it seemed, was casting an envious glance back - and in The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr we can see his canvases getting larger and his subject matter becoming grander. Although it was with The Resurrection of Christ that he seems to have really given free rein to his imagination. Look at the size of the Christ on that!

Giovanni Bellini - The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (c.1505-7)

Giovanni Bellini - The Resurrection of Christ (c.1475-9)

Andrea Mantegna - Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue (c.1500-2)

Giovanni Bellini - Doge Leonardo Loradean (c.1501-2)

He was still capable of small scale, contemplative, portraiture though and in the case of his famous Doge Leonardo Loradean he even allowed himself a rare lapse into the secular. Loradean was the 75th doge (chief magistrate) of Venice and, according to Wikipedia - you don't think ALL of this is stored in my brain do you?, the most important the city ever saw. I love the way the blue background juxtaposes against his solemn and sombre face.

Titian and Dosso Dossi were called in, after the fact, to add a few details to Bellini's Feast of the Gods which may have a 1930s Disney colour scheme going on but certainly seems to show one hell of a party going down. There are people balancing saucers on their heads, a woman helping herself to a libation, a pie eyed chap in a fetching red sash staring gormlessly out at us, and one dude seems to have the hind legs of an ass. We've all been there....

Giovanni Bellini (with later additions by Titian and Dosso Dossi) - Feast of the Gods (1514-29)

Giovanni Bellini - The Drunkenness of Noah (c.1515)

....and we've all woken up the next morning like Noah (above). He's gonna have a sore head - and it's still over four centures before ibuprofen will be discovered. A wasted pre-Flood Patriarch wouldn't normally be one of the most identifiable paintings in an exhibition but such is the sheer insanity of Christianity (I mean, at times you start to wonder if they just made it all up) that I found myself feeling quite tempted to get as messed up as Noah (and I hadn't even saved all the world's animals from drowning). I didn't though. I got the train home, scoffed a pack of Mini Eggs (that's an Easter thing so that makes me observant, right?), and then tried to fit a narrative around a story that really doesn't make any sense but has certainly thrown up some wonderful and intriguing art.

I was flippant in my assessment, and will continue to be rude about religion - I'm not killing religious people like they have (and continue to do so) with non-atheists, but out of respect for the 'faith' of those who do believe I'll leave the last paragraph to Giorgio Vasari. A learned scholar and respected source on Renaissance art no doubt, but also a brown noser of the highest order who, of Mantegna, has this to say:-

"Andrea was so kind and lovable that he will always be remembered not only in this country but all over the world. He was rightly praised by Ariosto at the beginning of Canto XXXIII where the poet places him among the greatest painters of his time: Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino".

Vasari did not give Giovanni Bellini a chapter. Ouch!

I was flippant in my assessment, and will continue to be rude about religion - I'm not killing religious people like they have (and continue to do so) with non-atheists, but out of respect for the 'faith' of those who do believe I'll leave the last paragraph to Giorgio Vasari. A learned scholar and respected source on Renaissance art no doubt, but also a brown noser of the highest order who, of Mantegna, has this to say:-

"Andrea was so kind and lovable that he will always be remembered not only in this country but all over the world. He was rightly praised by Ariosto at the beginning of Canto XXXIII where the poet places him among the greatest painters of his time: Leonardo, Andrea Mantegna, Gian Bellino".

Vasari did not give Giovanni Bellini a chapter. Ouch!

Monday, 21 January 2019

No Lines in Nature:Samuel Courtauld and the Passion for 19c French Art.

"We live in a rainbow of chaos" - Paul Cezanne.

Businessman, collector, and philanthropist Samuel Courtauld appears to be one of the only people in the UK in the period between the wars who had both the wherewithal, the passion, and the faith in vaguely contemporary European art (French, mostly) to be able to, and want to, buy it. This was possibly down to his own Huguenot background, we can't be certain. What we can be sure of is that he bought painting after painting by artists who are now considered the most vital of their and, in some cases, any era.

It was an age when Britain was suspicious of anything European (heaven forbid we would ever be so stupid and insular ever again) and it's thanks to Courtauld, possibly more than any other person, that we now have such a rich, and often freely available to view, selection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in the UK. London, of course, is particularly well served:- after Courtauld's wife, Elizabeth, died he left much of his collection to his own Courtauld Institute for both conservation and teaching of art history.

Yesterday saw the last day of the National Gallery's Courtauld Impressionists:From Manet to Cezanne show which combined works you can normally see at the Courtauld with those usually held (and available for free - so charging was a bit cheeky, but it was cheap) in the National Gallery. I'd left it late (and I was far from the only one, it was rammed) but I was glad I squeezed it in. It was definitely worth it. A great show.

You'd think the lack of a commercial imperative would give him leeway to be the more interesting painter but, to my eyes, that's just not the case. Degas' work has dated in a way that Manet's, Van Gogh's, and Cezanne's has not. I'm not doubting his technical ability, the ballerinas dancing to Mozart's Don Giovanni and the young, and mostly naked, Spartans, exercising are all brilliantly executed, but I am saying that in contrast to his contemporaries he is the weaker artist.

Businessman, collector, and philanthropist Samuel Courtauld appears to be one of the only people in the UK in the period between the wars who had both the wherewithal, the passion, and the faith in vaguely contemporary European art (French, mostly) to be able to, and want to, buy it. This was possibly down to his own Huguenot background, we can't be certain. What we can be sure of is that he bought painting after painting by artists who are now considered the most vital of their and, in some cases, any era.

It was an age when Britain was suspicious of anything European (heaven forbid we would ever be so stupid and insular ever again) and it's thanks to Courtauld, possibly more than any other person, that we now have such a rich, and often freely available to view, selection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in the UK. London, of course, is particularly well served:- after Courtauld's wife, Elizabeth, died he left much of his collection to his own Courtauld Institute for both conservation and teaching of art history.

Yesterday saw the last day of the National Gallery's Courtauld Impressionists:From Manet to Cezanne show which combined works you can normally see at the Courtauld with those usually held (and available for free - so charging was a bit cheeky, but it was cheap) in the National Gallery. I'd left it late (and I was far from the only one, it was rammed) but I was glad I squeezed it in. It was definitely worth it. A great show.

Camille Pissarro - The Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897)

It could hardly have failed to be, really. Both Manet and Cezanne are two of the most important figures in 19c art, all art, and the links between them (Monet, Seurat, Pissarro, Gauguin, van Gogh) were no slouches either. There were a couple of outliers, the odd curveball, but for the most part the exhibition traced the story of how the Impressionist artists first appeared, how they developed, and how, eventually, they paved the way for Cubism and even Abstraction.

Not only was Manet not popular in Britain, they didn't even like him in France. Not the art critics anyway. Or the general public. Charles Baudelaire, Emila Zola, and Stephane Mallarme were all fans and contemporaries and each of them loved the way he radically reinterpreted themes and motifs he'd studied in paintings by Renaissance masters like Titian and Velazquez.

Not only was Manet not popular in Britain, they didn't even like him in France. Not the art critics anyway. Or the general public. Charles Baudelaire, Emila Zola, and Stephane Mallarme were all fans and contemporaries and each of them loved the way he radically reinterpreted themes and motifs he'd studied in paintings by Renaissance masters like Titian and Velazquez.

In 1862, the year of his thirtieth birthday, Edouard Manet made his first major painting of city life. To our modern eyes, it's nothing spectacular. Nothing special even. But, at the time, audiences were perplexed by both the composition, the less than starchy subject matter (friends and family listening to a concert in a park), and even the unorthodox position Manet must have placed himself in to capture the scene.

Edouard Manet - Music in the Tuileries Gardens (1862)

Edouard Manet - Dejeuner sur l'herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) (about 1863-8)

He was soon to go further. Dejeuner sur l'herbe was dismissed by the Salon in Paris but did find some exposure in an exhibition of rejected works. The nudity caused a sensation. In those days it would have been due to the female sitter's lack of 'decorum', one would presume. Now, and not least because the men in the painting are dressed, it would be seen as patriarchal and indicative of the male gaze. The Guerrilla Girls once asked 'do women need to be naked to get in the Met Museum?' and that question, although not in Manet's time being asked, would have been equally pertinent in 1860s Paris.

Times change and we could argue the toss about its meaning (or if it's demeaning) until les vaches come home but what's not in doubt is that's a wonderfully rendered, amazingly free, piece of painting. A Bar at the Folies-Bergere is better still. According to Jonathan Jones reviewe for this very show in The Guardian it surpasses even Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon as THE greatest masterpiece of all modern art.

I'm not sure I'd go quite as far as Jonathan. I'm not even certain it was the best, or most important, painting in the show - but it is both excellent and intriguing. The reflection behind Suzon the barmaid does not match that which is being reflected, the details of the faces of the customers in the bar are rendered blank as periphery people are when you're focusing on one specific person, and Suzon herself looks utterly unmoved by the situation. You could say she is a study in boredom but the French word, ennui - of course, seems to capture the mood so much better.

Edouard Manet - A Bar at the Folies-Bergere (1882)

My friend Dan noted that, amongst the wine and oranges, there are two bottles of Bass beer. Bass was brewed in Burton-upon-Trent, suggesting that 1880s France was not as stuffy about Britain as Britain can often be about Europe. A lot of Manet's work appears to make use of a dark, muted palette and is often set indoors but Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil looks like not just an influence on the artists that followed him, but could easily be mistaken for one of their works.

So it came as no surprise that Manet painted this while visiting Claude Monet in the suburbs of Paris. In fact the lady and her child looking out to the river are Monet's wife and son, Camille and Jean. Like some of Monet's work, those now accustomed to more anarchic, edgier, or more conceptual art may throw that tired old curse, 'biscuit tin', at it. Once, though, this was a daring way of painting - and, anyway, I like biscuits and you've got to keep them somewhere.

So it came as no surprise that Manet painted this while visiting Claude Monet in the suburbs of Paris. In fact the lady and her child looking out to the river are Monet's wife and son, Camille and Jean. Like some of Monet's work, those now accustomed to more anarchic, edgier, or more conceptual art may throw that tired old curse, 'biscuit tin', at it. Once, though, this was a daring way of painting - and, anyway, I like biscuits and you've got to keep them somewhere.

Edouard Manet - Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil (1874)

Claude Monet - Antibes (1888)

Manet's 'Monet' looks more like a Monet than the Monet hanging across from it. Antibes is a beautiful, wistful painting that captures the feeling of staring out to the sea to ease one's troubled mind, soaking in the glory of nature when real life (whatever that is) gets a bit too much. As the curators of the show have correctly pointed out it captures something of Monet's fascination with the Japanese artists Hokusai and Hiroshige, a fascination shared by James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

In its plein-air style Antibes was typical of Monet, but the Mediterranean setting was in stark contrast to his more typical grey northern skies. It was some years before this painting was made, in 1872, that he painted Impression, Sunrise - the painting that gave the loosely affiliated movement its name and it was in 1874 that Monet, Degas, and Pissarro started to exhibit their work independently of the uninterested and dismissive Salon.

Degas was more of a pain in the arse than most of the others. A racist and a sexist (neither of which were probably uncommon at the time) who slagged off his contemporaries unceasingly and shunned painting outdoors for scenes of ballet and horse racing. He was also richer than the others too so he didn't really need to worry if anybody bought his paintings.

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - Two Dancers on a Stage (1874)

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - Young Spartans Exercising (about 1860)

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - Woman at a Window (about 1871-2)

But, hey, as we've established, he was up against VERY tough competition. Perhaps if he'd stopped slagging them off and listened to what they were saying he may have done better (#justsaying). Knowing his views on women I'm a little concerned that the panel next to his Woman at a Window states it was painted during the Franco-Prussian war, when Paris was under siege, and that the model was starving. When Degas offered her a hunk of meat (no sniggering at the back) 'so hungry was she, she devoured it raw'.

If Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (a treble barrelled forename, ffs, how pretentious can 'one' get?) is an outlier due to being less innovative than the others, then Honore-Victorin Daumier, who was happy with just two first names, is an outlier by dint of his age. He was older than the rest of the artists on show here and, to be honest, he doesn't quite fit in. A dad who has arrived at the party to pick his kids up a bit too early.

Daumier was a caricaturist, a draughtsman, a printmaker, and a cartoonist fond of satire and social commentary. Though none of that is represented here. Instead we're treated to two, vastly different illustrations of scenes from Cervantes 17c novel Don Quixote. They are both, apparently, "imbued with deep personal meaning" which is all well and good but Daumier died 140 years ago, so we can assume that deep personal meaning died with him. For what it's worth I prefer the top, more modern, slightly darker, one.

Daumier was a caricaturist, a draughtsman, a printmaker, and a cartoonist fond of satire and social commentary. Though none of that is represented here. Instead we're treated to two, vastly different illustrations of scenes from Cervantes 17c novel Don Quixote. They are both, apparently, "imbued with deep personal meaning" which is all well and good but Daumier died 140 years ago, so we can assume that deep personal meaning died with him. For what it's worth I prefer the top, more modern, slightly darker, one.

Honore-Victorin Daumier - Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (about 1868-72)

Honore-Victorin Daumier - Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (about 1855)

Palate cleansed by Daumier's atypical inclusion, I was ready to gorge on one of the finest selections in the whole show. Camille Pissarro may not be has highly regarded as some of his friends but, personally, I've always been a huge fan - and that's not just because he lived briefly around Dulwich, Sydenham, and Crystal Palace and made many painting of SE London.

His lengthy career spans from an apprenticeship as Corot's pupil through to working with Cezanne and, in the knowledge that he was a modest, kindly man, it seems that his reputation may have suffered as he let those with bigger egos take centre stage. If that's so, that's a real shame. In his adoption, along with Seurat, of Pointillism he seemed eager to embrace the new rather than rest on his laurels, something he has in common with another South Londoner, a certain David Bowie!

1897's The Boulevard Montmartre at Night is one of my two very favourite paintings in the show (that's why it's right up there at the top). I love the way he didn't baulk at the new fangled electric street lights, that he didn't see them as anathema to art but as a new challenge. I love, even more, the way he's caught the glimmer, the radiance, the buzz of modernity they would have brought with them, and the thrill of the Paris air at night.

Place Lafayette, Rouen is pretty damned good too. I loved finding out that on arrival in Rouen, Pissarro decided to give the picturesque medieval town centre a miss and set up his easel near an industrial centre and commercial port. He wasn't looking to paint ugly but to capture the beauty of the everyday and I think he's managed it astoundingly well. You can see in this work how he was beginning to forge the technique of building up a painting by the use of dots. A style that would become known as Pointillism and would be perfected by Georges Seurat.

Camille Pissarro - Place Lafayette, Rouen (1883)

Georges Seurat - Bridge at Courbevoie (1886-7)

Who knows what Georges Seurat would have gone on to achieve had he not died (of an unspecified disease) at the preposterously young age of thirty-one. He achieved quite a lot in his short life as it was. Not fully satisfied with the Impressionist painters intuitive responses to light and colour, Seurat sought to use optical theories to both rationalise and maximise his approach. It can sound cold and calculated but you only to have look at his work to see it had quite the opposite effect.

Somebody once told me they thought to be rational was to mean you could not be passionate and that to be passionate meant you could not be rational. I felt then, and I feel know, that was hokum of the highest order and I would suggest even a cursory glance at Seurat's Bridge at Courbevoie would prove so. Science and mathematics CAN be applied to art and that art will be no weaker for it. In the case of Georges Seurat, it will be stronger.

It's a marvellous painting. I love the stock still men staring out at the chilly looking waters, the sails on the boats, the green of the riverside, and the shadowy figures lurking in the background, and I love too that, right to the rear of the painting, there is a smokestack billowing out what looks more like confetti than smoke. Bridget Riley must have been a fan?

I'd imagine most artists of the time would shy away from including chimneys belching out industrial waste into the sky in their paintings, not least if those paintings were supposed to picture idyllic scenes, but to me it's part of what makes them. The Bathers at Asnieres, in what must surely be Seurat's most well known painting, aren't rich playboys, lotus eaters, or parishioners of paradise but ordinary folk who had to enjoy their summer in their lunchtime, after work, or at the weekends. They had to make the most of what they had and it's this sense of being aware that these pleasurable hours will soon be done that gives the work its strength. I'd even go so far as to claim it as a memento mori.

Georges Seurat - Bathers at Asnieres (1884)

Georges Seurat - The Channel of Gravelines, Grand Fort-Philippe (1890)

Less celebrated but, to me, equally superb is The Channel of Gravelines. What a strange, nondescript place to make the subject of a painting. A couple of cottages, a barn, a slightly bigger house, an empty boat, a canal, a huge expanse of, well, nothingness. It elicits in me feelings of sadness, feelings of despair, yet, simultaneously, feelings of joy and expectation. It is a painting I've been staring at in the National Gallery for years, decades even, now and it is still one that has yet to fully reveal its mysteries to me. They continue to deepen and, one thing about me, I love an ever deepening mystery.

Georges Seurat - Young Woman Powdering Herself (about 1888-90)

Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec - Woman Seated in a Garden (1891)

Which is maybe why, following Seurat, I brushed past the section on Toulouse-Lautrec with almost indecent haste. His interesting life story (born into one of France's oldest aristocratic families, laid low by accidents and illness) and interesting life (hanging around with bohemian types, cabaret singers, and prostitutes in Montmartre), for me, overshadows his art. It's good but in this sort of company he comes across as a minor artist, a footnote.

Renoir, too, also suffers in comparison to what has been (and what is still to come). Again, he's good. He's just not quite good enough when he's in the ring with the big boys. Both The Skiff and La Loge are almost textbook Impressionism. If you wanted to show an alien what Impression is/was you could do a lot worse than start with them. They would explain both plein-air painting, interior scenes, and the Impressionist obsession with all things theatrical, though more often the audience than the performers.

Renoir, too, also suffers in comparison to what has been (and what is still to come). Again, he's good. He's just not quite good enough when he's in the ring with the big boys. Both The Skiff and La Loge are almost textbook Impressionism. If you wanted to show an alien what Impression is/was you could do a lot worse than start with them. They would explain both plein-air painting, interior scenes, and the Impressionist obsession with all things theatrical, though more often the audience than the performers.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir - The Skiff (La Yole) (1875)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir - La Loge (Theatre Box) (1874)

Vincent van Gogh - A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (1889)

But put either of them next to Vincent van Gogh's Wheatfield from just fifteen years later and they look like the art of the past. It's men against boys. Things were moving pretty quickly. The game was nearly up for Impressionism. It had done its job, it had changed how art was made and how art was looked at, and it was time to move on. Seurat, van Gogh, Gauguin. and Cezanne were the artists who were to do that.

It's easy now, and cliched too, to say you can see something of van Gogh's inner turmoil and turbulent life style in his art - but it's really difficult to avoid coming to those conclusions. Painted from a field near Arles in the south of France, just outside the asylum in which he was receiving treatment, it was the first van Gogh painting to enter a British collection but in its expressionistic clouds, windswept trees and wheat, and restless nature it captures the essence of both the man and his art. It's a pity it was the only van Gogh in the show. Predictably, it had drawn a crowd.

There was only one Pierre Bonnard piece in the show by the time I arrived too. There had been two but the second had been ferreted away to Tate Modern as their Pierre Bonnard:The Colour of Memory opens this Wednesday. Looking at the one Bonnard on show, he doesn't stand out as the most likely of artists to be given a retrospective by such an institution.

His "images of quiet interiors and radiant gardens" don't seem like the sort of subject matter to rub shoulders with the Kabakovs and Fahrelnissa Zeid and he was still practicing Impressionism long after most other artists of his era (Derain, Matisse) had moved towards Fauvism or Post-Impressionism. Yet Courtauld, and the curators of this exhibition, saw something in his work. They saw "a singular artistic vision" and "radical" investigations into composition and colour which, pleasant though it is, I just can't get from 1910's Blue Balcony. I shall endeavour to attend that Tate show and see if further exposure to his work can change my mind.

His "images of quiet interiors and radiant gardens" don't seem like the sort of subject matter to rub shoulders with the Kabakovs and Fahrelnissa Zeid and he was still practicing Impressionism long after most other artists of his era (Derain, Matisse) had moved towards Fauvism or Post-Impressionism. Yet Courtauld, and the curators of this exhibition, saw something in his work. They saw "a singular artistic vision" and "radical" investigations into composition and colour which, pleasant though it is, I just can't get from 1910's Blue Balcony. I shall endeavour to attend that Tate show and see if further exposure to his work can change my mind.

Pierre Bonnard - Blue Balcony (1910)

Paul Gauguin - The Haystacks (1889)

While Bonnard is still being reassessed, Paul Gauguin's place in the firmament has long been established and it's only recent, and long overdue, reassessment of his sexual peccadilloes (or full on abuse - you choose) that endangers it. As a man, it's very difficult to make a case for him. As a painter, it's a cinch. Works like 1889's The Haystacks show that Gauguin looked back to classical art as much as he looked forward to new developments and in its celebration of the simple, peasant - there's a loaded word, lifestyle we can witness both what made Gauguin great and what made Gauguin a man of great privilege.

As ever with privilege, it is the not knowing one has it that makes the wielding of it so easy, and so egregious. It was a long distance in miles but a very short one in morality from idolised peasant portraiture to jumping on a boat to Tahita and impregnating underage girls. These people were pure, untouched by civilisation, and Gauguin seemed to be unable to see that his arrival would be the very thing that would divest them of that 'purity'. How could it be? He was Gauguin. An artist. A lover of the simple life. It'd be instructive to learn how much interest he took in how the Tahitians actually lived and how much he just wanted to get his end away with exotic, and young, foreign women.

Yet, all these criticisms aside, paintings like Te Rerioa (The Dream) are utterly captivating. They draw you in. The colours are bright but not gaudy, the angles are unorthodox but not self-consciously so, and the whole composition is totally joyous. Gauguin, the swine, makes us implicit in his exploitation and we don't know how we feel about it.

Paul Gauguin - Te Rerioa (The Dream) (1897)

Paul Cezanne - Pot of Primroses and Fruit (about 1888-90)

At least with Cezanne, we are spared such moral quandaries. As van Gogh and Gauguin grabbed the headlines, outraged the art world, and subverted accepted ways of living (in very different ways - as Gauguin was shagging his way round the South Seas, van Gogh was chopping his own ear off), Cezanne quietly, methodically, and with no fanfare whatsoever, set about changing the way the whole world would look at art forever.

Gauguin showed one possible route, van Gogh another, Seurat another still, but it was Cezanne who found the key to the escape room, who forged ahead on his own, a true pioneer, beating a path that would soon be followed by the likes of Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and Gris. Not that many people saw it like that at the time, of course. Like Manet before him, Cezanne was rejected, time and time again, by the Salon, by the French art establishment.

As other artists looked to paint ever more shocking subject matter, Cezanne stuck to landscapes, fruit, and portraits. He wasn't so much interested in WHAT he was painting but HOW he was painting. He didn't want to show us what things LOOKED like. He wanted to show us what things ARE.

Paul Cezanne - Farm in Normandy, Summer (Hattenville) (about 1882)

Paul Cezanne - Lac d'Annecy (1896)

Over his career, Cezanne's paintings slowly developed into an almost gridlike proto-Cubist style. Lac d'Annecy makes exquisite use of a wonderful range of deep hues and evocative colours, Farm in Normandy is somehow greener than the green of other artists, and even the apples and pears of Pot and Primroses and Fruit, ingeniously, look both exactly like what they are and like something utterly unworldly at the same time. The gentle nature of Cezanne's art should never diminish his status as one of the art world's true titans.

By his fastidious nature and through a combination of hard work and inspiration, Cezanne had opened the door for the next generation (and the next, and the next, ad infinitum) to walk through. But if Manet had not opened the door for him, and then Monet, Pissarro, Seurat et al held it open, then maybe, just maybe, that may never have happened.

Courtauld Impressionists:From Manet to Cezanne did a very good job of cementing my belief that that's how it happened and almost every single painting within it was a joy to behold too. On exiting the gallery I walked out on to Trafalgar Square on a crisp, sunny, January Sunday afternoon. The white spire of St Martin-in-the-Fields stood proud against the clear blue sky. If it hadn't been so cold I could have been in Rome. Art, once again, had made me look at the world, look at MY world, in a different way. It had, briefly, lifted the shawl of depression and anxiety from my shoulders. It had served its purpose. I went for a coffee.

By his fastidious nature and through a combination of hard work and inspiration, Cezanne had opened the door for the next generation (and the next, and the next, ad infinitum) to walk through. But if Manet had not opened the door for him, and then Monet, Pissarro, Seurat et al held it open, then maybe, just maybe, that may never have happened.

Courtauld Impressionists:From Manet to Cezanne did a very good job of cementing my belief that that's how it happened and almost every single painting within it was a joy to behold too. On exiting the gallery I walked out on to Trafalgar Square on a crisp, sunny, January Sunday afternoon. The white spire of St Martin-in-the-Fields stood proud against the clear blue sky. If it hadn't been so cold I could have been in Rome. Art, once again, had made me look at the world, look at MY world, in a different way. It had, briefly, lifted the shawl of depression and anxiety from my shoulders. It had served its purpose. I went for a coffee.

Paul Cezanne - Hillside in Provence (about 1890-2)